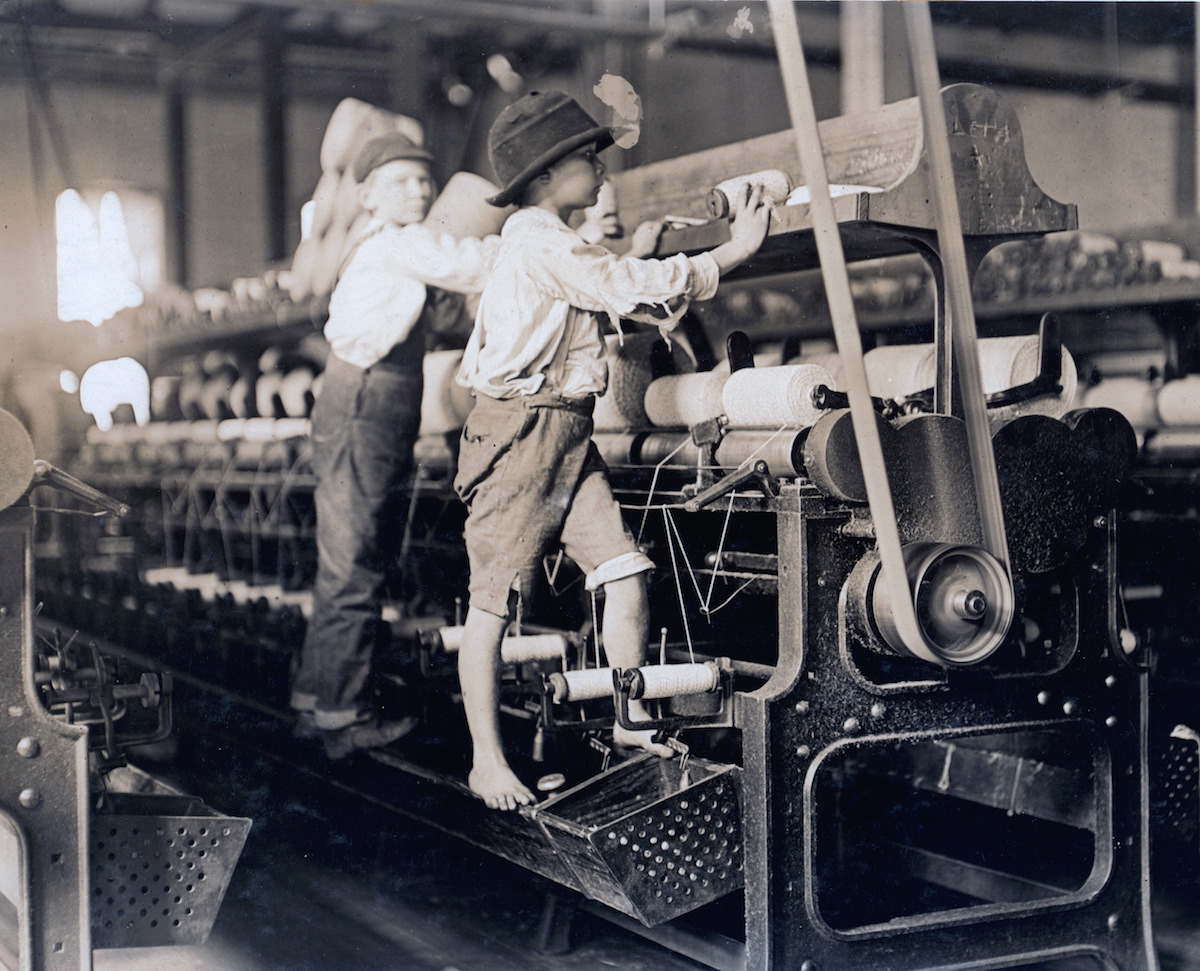

Imagine a nation in which millions of children, some as young as 5, worked. They toiled in coalmines, glass factories and textile mills, some up to 18 hours a day.

Imagine a nation in which employers paid workers as little as possible, many less than $1 per day.

Imagine a nation in which workers typically labored ten to 12 hours, six days a week—though some, as in the steel industry, worked seven days.

Though many Americans today might think of Social Security as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s most significant domestic achievement, it was another New Deal law that changed that nation into one in which children were protected, workers were fairly paid and hours were limited, to eight hours a day and five days a week. Though it has far less name recognition today, the Fair Labor Standards Act—the FLSA, signed on June 25, in 1938—changed the entire employment culture of the United States and easily rivals Society Security in its importance.

The law had a long road to passage. For years, whenever state and federal officials passed laws to protect workers, the U.S. Supreme Court had struck them down. Most importantly, the Court declared, in 1905’s Lochner v. New York, that a law establishing a 60-hour workweek was unconstitutional for violating the “sanctity of contract” and “economic liberty.”

The fight to prohibit child labor had been a cause célèbre among progressive reformers and Socialists for decades at that point. In 1903, legendary union radical Mother Jones castigated the legality of child labor: “Some day the workers will take possession of your city hall, and when we do, no child will be sacrificed on the altar of profit!”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Similarly, the struggle for the 8-hour day lasted most of a century. It moved forward on May 1, 1886, when hundreds of thousands of workers struck, nationwide, for the 8-hour day. The cause moved backwards three days later when, in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, a bomb killed eight policemen breaking up a meeting of anarchists who were protesting the police’s earlier killing of strikers.

It took the Great Depression, however, to make change stick. Fast-forwarding to the 1930s, ever more Americans supported reducing the workday. If workers toiled fewer hours, employers could hire more workers, which was a major concern during those years. Many also believed in “8 hours for work, 8 hours for sleep, 8 hours for what we will.” Some unions and even employers, most famously Kellogg, pushed the 6-hour day. So it should be no surprise that in his 1936 re-election campaign FDR championed the U.S. working class. “Something has to be done about the elimination of child labor and long hours and starvation wages,” he said. He won in a landslide.

Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor and first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet, led this effort. As early as 1911, after the tragic Triangle Fire killed 146 NYC textile workers, Perkins served the cause of working people, including pushing for what became the FLSA.

So, too, the increasingly large, vocal, and powerful labor movement, then split between the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, became famously “the folks who brought you the weekend.”

Resistance remained—the National Association of Manufacturers, for instance, asserted that the FLSA “constitutes a step in the direction of communism, bolshevism, fascism, and Nazism”—but the FLSA became law.

Today, most Americans still support the FLSA whether or not they know about the actual law. And, in the face of growing concern about economic inequality, FLSA provisions remain newsworthy.

For example, the fight for a higher minimum wage has proven quite successful in cities from Seattle to Birmingham voting to hike their minimum wages. Most recently, California and New York passed laws to gradually move towards $15 an hour. Last month, the Obama Administration announced a new rule that will increase the number of workers eligible for overtime by about 4,200,000. Alas, the global struggle against child labor still is an uphill struggle: the International Labor Organization reports 168 million children still work including 85 million in “hazardous work” worldwide.

Today, Americans take for granted minimum wages and overtime rates and the fact that children don’t work. But that’s only because laws like the FLSA protected—and still protect—American workers from the dangers of unregulated capitalism. The current push across the nation to drastically raise the minimum wage suggests a widespread belief in the efficacy of such laws. So, happy birthday to the FLSA and here’s to strengthening it further.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Peter Cole is a Professor of History at Western Illinois University. He is the author of Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive Era Philadelphia and currently is writing Dockworker Power: Race, Technology & Unions in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com