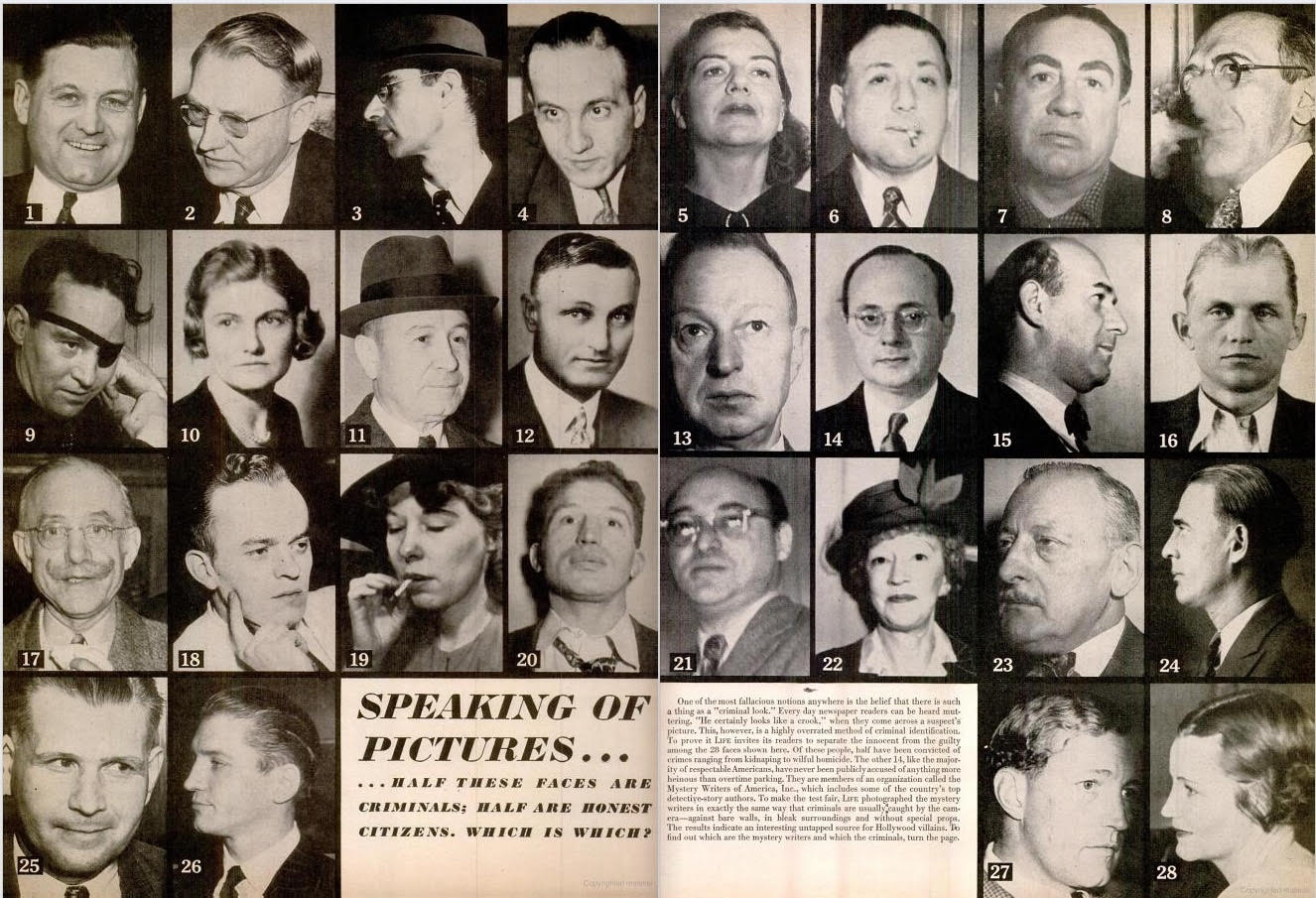

In its March 10, 1947 issue, LIFE magazine published a series of twenty-eight black-and-white photographs as part of its feature, Speaking of Pictures. Half of them were of criminals, some convicted of murder, kidnaping, and rape. They were mixed in with another half that were photographs of members of the Mystery Writers of America. The magazine’s readers were asked to distinguish between the criminals and “honest citizens,” with the text that clarified the identity of each person to be found only after turning the page.

The editors explained their strategy: “To make the test fair, LIFE photographed the mystery writers in exactly the same way that criminals are usually caught by the camera—against bare walls, in bleak surroundings and without special props.” The readers were asked to see if they could “separate the innocent from the guilty.” Anticipating that the readers would fail, the magazine suggested that picking out the “criminal look” should be considered “a highly overrated method of criminal identification.”

But the ruse was much more complex than simply comparing faces, and there was no straightforward photographic strategy employed “to make the test fair.” Some people were respectfully photographed from slightly above, and others disrespectfully from below, the camera looking up their nostrils. Some were aggressively photographed with a direct flash, and others with a muted light. There were also various social cues provided: certain subjects were depicted with cigarettes in their mouths, some had their hats on indoors, one had an eye patch, a few wore eyeglasses, and a number of the men were shown in jackets and ties. All of them were white.

One bespectacled man in a jacket, white shirt and tie, seated as if for an author’s photograph, was identified in the answer key as “a Colorado choir singer” who “made a good living marrying ladies that he met at church socials. They all ‘died’ suddenly. His stretch: 126 years.” A more nattily dressed man photographed as if for a yearbook was described as a Texas attorney who “murdered his wife with dynamite in 1930. While waiting for his trial he killed himself with another charge.”

For an astute reader the subtext of this exercise was that if one depends upon the publication to use photographs to accurately depict the subject, any subject—including politicians, celebrities, or anyone else—the reader might well be sorely misled. Neither a person nor a photograph should be taken at face value; it is more complicated than that.

Read next: What a Photograph Can Achieve

More recently, the delayed release of the mug shot of Brock Turner, the Stanford student-athlete who was convicted of sexual assault earlier this month, sparked outrage. After many requests by media outlets, law enforcement officials finally released two images only after his sentencing for three felony convictions, including one from his booking over sixteen months before. Instead, yearbook-style smiling photographs of him with a tie and jacket were previously published. This appeared to be preferential treatment symptomatic of a culture of white male privilege that contributed to the light six-month sentence in county jail that Turner received from the judge, so as not to “have a severe impact on him.”

The articulate, pain-filled letter written and read in court by his victim makes it clear that her relationship to photography was quite different than that of her attacker, beginning with her desire to remain anonymous. But it is more complicated than that: “My clothes were confiscated,” she wrote about her experience after the assault, “and I stood naked while the nurses held a ruler to various abrasions on my body and photographed them. The three of us worked to comb the pine needles out of my hair, six hands to fill one paper bag. To calm me down, they said it’s just the flora and fauna, flora and fauna. I had multiple swabs inserted into my vagina and anus, needles for shots, pills, had a Nikon pointed right into my spread legs.”

Photographs were also used to re-victimize her and her family, their evidentiary quality challenged by Turner’s lawyer: “My family had to see pictures of my head strapped to a gurney full of pine needles, of my body in the dirt with my eyes closed, hair messed up, limbs bent, and dress hiked up. And even after that, my family had to listen to your attorney say the pictures were after the fact, we can dismiss them.”

Many wanted to have had a mug shot released that demonstrated that a white student from an elite university held on sexual assault charges would be treated, at the very least, like everyone else. Nor should he be treated in a way that was so strikingly advantageous compared to the treatment of people of color, particularly young black men. The recent Twitter campaign, #IfTheyGunnedMeDown, which emerged following the fatal police shooting two years ago in Ferguson of an 18-year-old, unarmed youth, Michael Brown, was a protest against the media’s tendency to immediately stigmatize Brown and others as members of gang culture, engaged in dubious activities, in order to criminalize them, making their deaths seem somehow merited. The Twitter campaign showed two images of each person, one that each author felt the media would more likely publish to fit a racist stereotype if he or she were shot, and the other a more banal image that showed the person engaged in the activities of daily life, such as playing music in the high school band or giving a speech.

Overall we live in a changed image culture that makes the 1947 LIFE magazine feature seem both prescient, as with the Twitter campaign above, and quaint. The proliferation online of public domain mug shots is enormous, so that search engines now organize them according to “vintage,” “prettiest,” “funny,” “hilarious,” “crying,” “celebrity,” “murderers,” and others. (Jeremy Meeks, whose mug shot went viral in 2014, came out of prison to numerous offers for a modeling career.) The availability of these mug shots has also spawned a deplorable website industry that requires people to pay to have their mug shot removed, even if they had been judged innocent or the charges were dropped. Italian artist/hacktivist Paolo Cirio claims that he has obscured 15 million online mug shots in the U.S. to make the people depicted unrecognizable, as well as shuffling around names and charges associated with each image so that the database is unusable. In a project called Obscurity, Cirio is attempting to assert people’s right to be forgotten; mug shots can be easily searched by potential employers, among others.

Read next: Why Violent News Images Matter

It is difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain guilt according to a photograph, but certainly there are image strategies available to make certain people appear more deserving of condemnation than others. But these are not always the obvious ones. In the two mug shots finally released of Brock Turner he seems less confident, but they are hardly condemnatory. In this increasingly populist era of anti-elitism, sometimes the appearance of certain kinds of privilege, as in his yearbook photos, might provoke the anger and denunciation that the mug shots do not.

With billions of photographs being uploaded daily, it is gratifying that certain photographs are still thought to have specific roles in society, and that the absence of a mug shot can cause an uproar. But we should be careful not to automatically rely on photographs for a revelation of one sort or another; we all know that they can be, and are constantly being, manipulated. And some aspects of life, including the most profound, may not be evident in a photograph. As the woman attacked by Turner wrote, “ Just like what he did to me doesn’t expire, doesn’t just go away after a set number of years. It stays with me, it’s part of my identity, it has forever changed the way I carry myself, the way I live the rest of my life.”

Fred Ritchin is Dean of the School at the International Center of Photography.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com