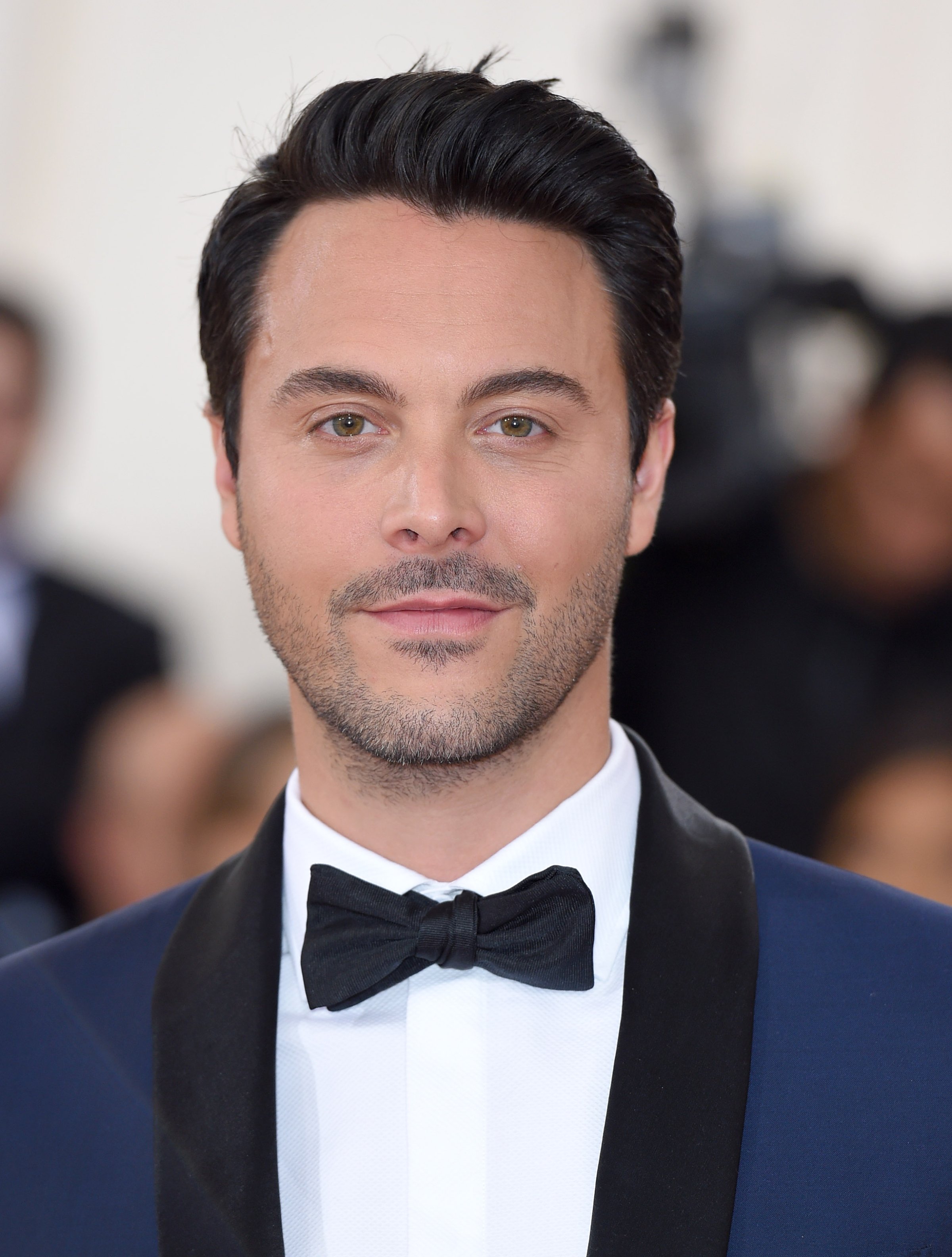

Jack Huston has gotten a lot of questions about why in the world he would take part in the reimagining of a movie that changed the face of cinema forever. When Ben-Hur was released in 1959, it broke multiple records: it was the most expensive and third longest movie ever made on the largest set ever constructed. Its yield of 11 Academy Awards remains unbeaten. Even now, in the era of reboots, it’s a tall order to tackle such a tentpole of cinematic history.

Well, says the former Boardwalk Empire star, first of all, director Timur Bekmambetov’s new Ben-Hur isn’t a remake of William Wyler’s classic film; instead, it’s an adaptation—the fourth (to Wyler’s third)—of Lew Wallace’s 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. And what is adaptation if not interpretation?

“The book is sort of like a landscape. If you got four artists to paint the same landscape, you’d end up with four very different paintings,” says Huston. “The thought that once a landscape has been painted by one artist, no one should touch it again—isn’t that the beauty of this profession?”

For the uninitiated—as many who see Ben-Hur when it opens on Aug. 19 surely will be—Wallace’s story follows the wealthy Jewish prince Judah Ben-Hur (Huston), a contemporary of Christ, who has a falling out with his best friend, Messala (Toby Kebbell). As a Roman commander, Messala condemns his ex-friend to certain death as a galley slave. But this is a story of hard-won redemption and iron will, and Judah not only survives the ordeal but goes on to challenge Messala in a chariot race of epic proportions. Morgan Freeman shows up to train him and Rodrigo Santoro appears as a Jesus whose face could easily make converts of heathens.

Huston, who comes from a long line of performers including his aunt, Anjelica Huston, grew up watching Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur every Easter, and he’s as worshipful of that movie as he is insistent on his movie’s distinctness from it. “It’s one of those seminal moments the first time you watch Ben-Hur because of the size and the scope and the epicness of a movie like that,” he says. “What we’ve made is drastically different from the ‘59 version, as that was very different from the ‘27 version, as that was different from the 1909 version. When I read [the script] it didn’t feel like I was stepping on the sandals of any of these guys.”

Slipping into his own pair was as physical a challenge as it was psychological. The various chapters of the saga required that he significantly change the shape of his body and test its capabilities. He lost 30 lbs—off a frame that doesn’t exactly have 30 lbs. to lose—in order to play a near-fatally malnourished slave. And then there was learning to drive a chariot for the movie’s high-octane finale, which employs impressively little CGI.

To master the ancient tradition, Huston worked his way from sitting in a chariot cart with two horses, to standing, and eventually to commanding four horses while standing. He considers chariot racing the NASCAR of its time, only much dustier. “You can’t see anything because there’s sand and dust, the horses are kicking back in your face, other people are crossing in front of you. It’s insane.” And there’s little room for error. He adds, rather gravely, “You’ve got to be rather masterful at the end of it because one slip up and you die.”

Of course, as much as action with the possibility of a gruesome, horse-trampled death may be a selling point for the some viewers, it’s intended to be a deeply emotional story too. For Huston, Judah’s journey is one that traverses the fine line between love and hate. “You can be driven by love as you can be driven by hate,” he says. Though Judah’s hatred for Messala drove him to survive what he should never have survived, it turned out to be a temporary shroud for love. “You don’t really hate anything you don’t love,” Huston says. “At the end, I think you realize maybe it was love all along.” And that’s a story that never gets old.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com