The Iranian revolution, which deposed the Shah, the nation’s monarch and turned the country into a religious Republic, broke out when Navid Khonsari was a young boy. During the early peaceful protests, he would accompany his grandfather in the streets, but as the confrontations grew more and more violent, he found himself confined to his home. A martial law was declared, curfews were imposed and schools were shut down. In the matter of a few months, he saw hope for change transform into chaos and violence. “Though I didn’t have the maturity to understand the politics of it, I could appreciate the emotions behind it,” he recalls. Eventually his family fled to Canada.

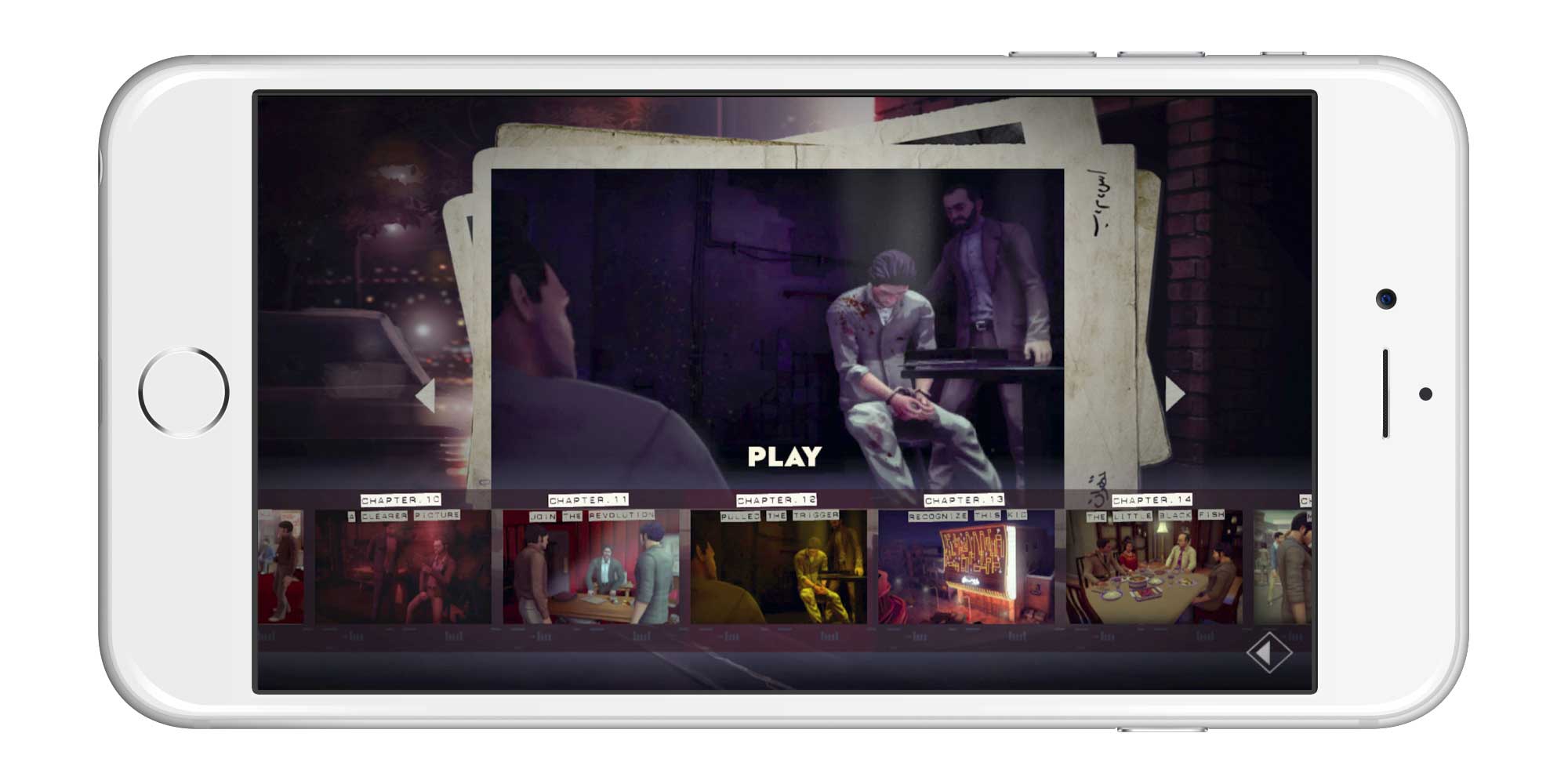

Over three decades later, based on his experience, that of his compatriots and other witnesses, he created a video game, 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, which purports to place the player in the heart of the events, as Reza Shirazi, an 18 year-old aspiring photographer who just returned to Iran after studying abroad. (The game is available now on PC and Mac computers, and will be released on the iOS platform on June 16, 2016).

“Video games are another medium through which people can express themselves and share stories,” says Khonsari. “We’ve already seen some that translate a personal experience into play. But, in our case, it wasn’t only personal. We were telling a story that affected an entire country and had reverberations throughout the world. That’s a big responsibility and there were no templates to draw from.”

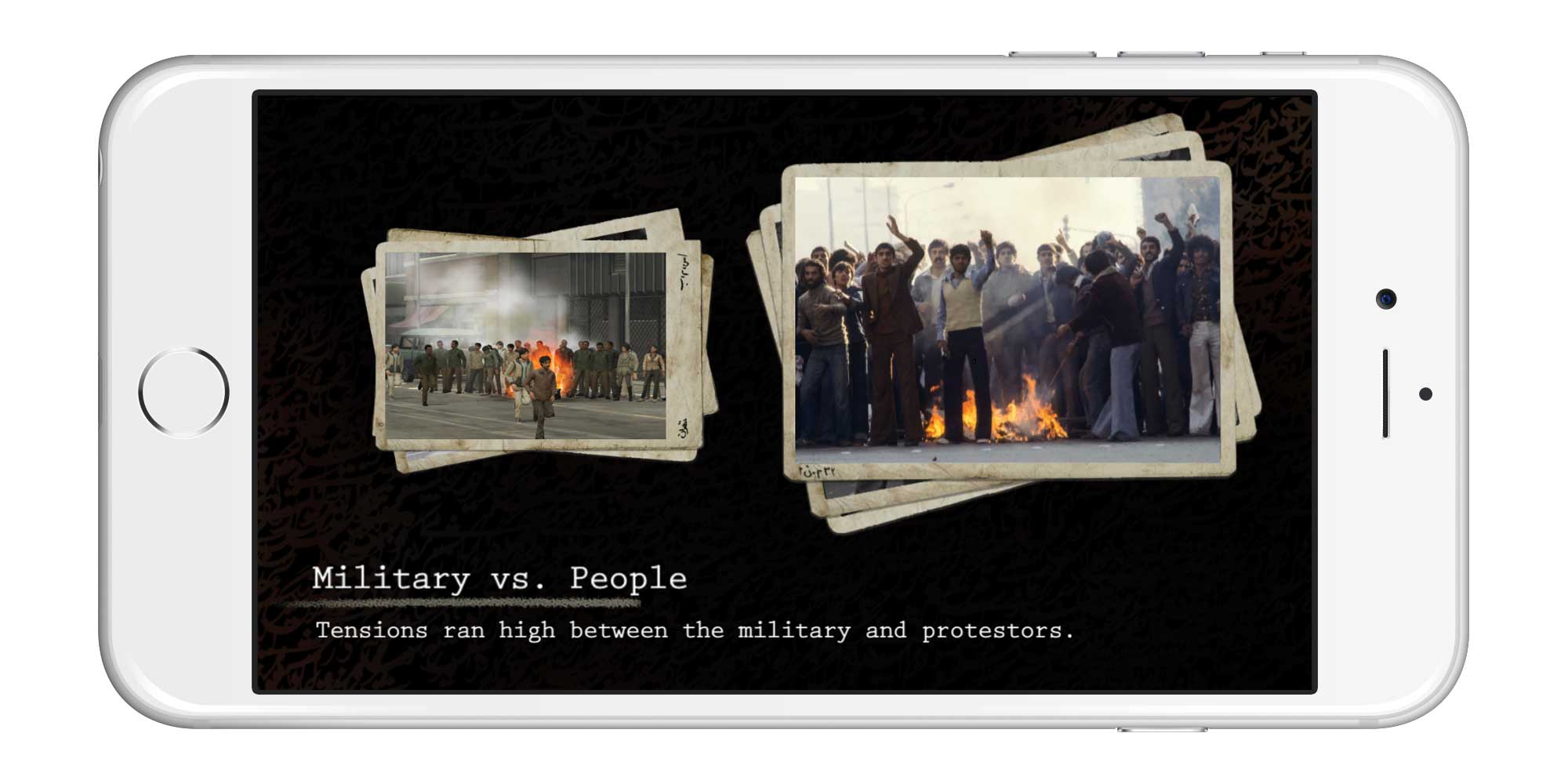

The idea for 1979 Revolution: Black Friday emerged after a meeting with Michel Setboun, a French photographer who was in Iran at the time. He documented the Shah’s family opulent life, covered the violent repression of protesters, including the shootings in Jaleh Square which killed and wounded dozens on September 8, 1978 − a day that became known as “Black Friday” − and followed Ayatollah Khomeini during his exile in France and as he took power in Iran.

“I’m very interested in the moral and philosophical choices that war correspondents must make when they’re at ground zero,” says Khonsari. “For instance, at what point do they make the decision to actually disengage from photography and get involved, or how do they continue to be convinced that their pictures have a greater impact than actions? I believe that anybody who has ever seen an incredible image that captures a horrific moment asks themselves what they would have done had they been in the photographer’s shoes.”

The game’s entire plot is premised on that very question as the player controls Reza Shirazi’s fate by determining how he will act given the circumstances he finds himself enmeshed in. Will he throw rocks at the soldiers who came to arrest political activists or photograph the unfolding scene? Will he give these same activists access to his photos, so they can identify a mole within their ranks? And, just as in real life, the choices must be made in a matter of seconds, the range of options is limited, and the long-term consequences unclear.

The situations the player, as Reza, face are based not only on Setboun’s photos, but also on the many testimonies Khonsari and his team at InkStories collected from scholars and Iranians who lived in Tehran at the time of the Revolution. Hailing from different backgrounds, they spoke about the economic disparities and the political tensions that arose within a country that operated as a pseudo-democracy, as well as the constant feeling of being stuck between a rock and a hard place. Because the game is based on real events, real stories, and real people, its director calls it a vérité game: the narrative is flexible, the backdrop, authentic.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday blurs the lines between fiction and reality. The graphics and the tone, reminiscent of popular games, such as Grand Theft Auto and Max Payne − on which Khonsari worked − makes it clear that the experience is virtual. Yet, the characters and plot points shift between being factual and imagined. Reza is made-up; Asadollah Lajevardi, his interrogator, was the actual warden of the infamous Evin Prison. We hear a historical recording of Ayatollah Khomeini; and the speech delivered by one of the revolution leader in the game, Abbas, is invented. Keeping track of the real and the fabricated can be, at times, rather confusing.

In this sense, the game is better understood as a gateway to the Iranian revolution. “We wanted to draw people by requiring them have to make choices as if they were in a political thriller. Through that experience they get to engage with history,” says Khonsari.

Still, its message is radical enough to concern the Iranian authorities, which not only decided to ban the game, but also claims to be developing a counter version. “That a video game can actually shake the foundation of a regime and question its legitimacy is quite telling,” says Khonsari. “It’s a reflection of the government’s lack of confidence in what they’ve done with the revolution.”

Laurence Butet-Roch is a Canadian freelance writer, photo editor and photographer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com