While the world remains fixated on the US presidential election, the political tides have begun to turn in its neighbor to the south. These 5 facts explain what you need to know following this weekend’s surprising regional elections in Mexico.

1. The Setup

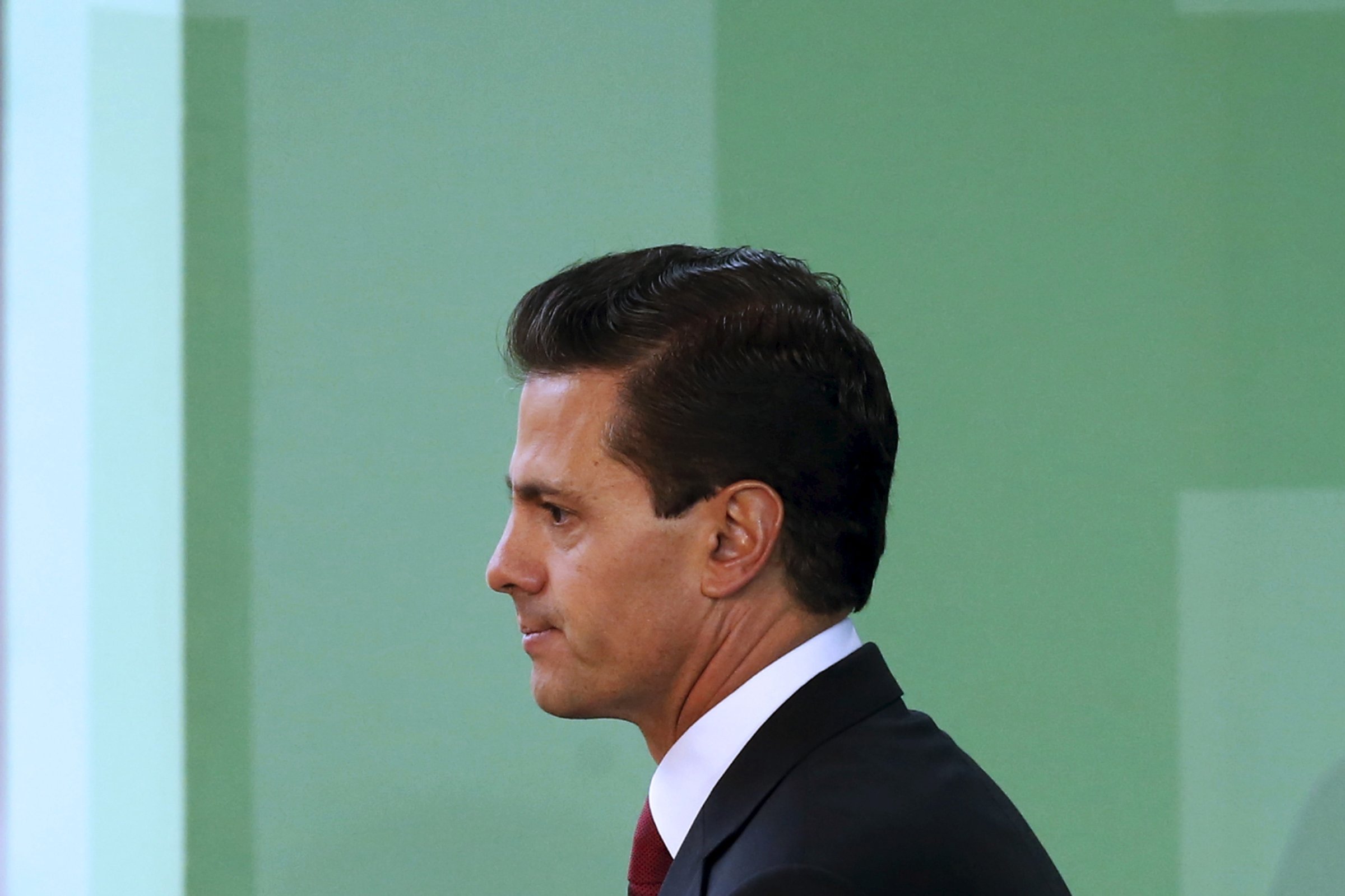

In a shock to pollsters, Mexico’s ruling party—the centrist PRI—lost 7 of the 12 governor’s races to its rivals, dealing a blow to the standing of Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto. Pena Nieto first took office in 2012, and his technocratic cabinet hit the ground running. The early returns were impressive; by 2013, Mexico’s economy was growing at a 1.4 percent clip. It’s been chugging along ever since, and the World Bank estimates it will continue growing between 2.5-3.2 percent annually to 2018.

At the heart of this revitalization has been Pena Nieto’s embrace of market- and investor-friendly reforms that boost competition and production, especially of oil. Pena Nieto has made an historic push to liberalize the sector, no easy feat when you consider that state owned Petroleos Mexicanos, known as PEMEX, is responsible for roughly a fifth of the government’s budget. PEMEX is woefully inefficient. Opening the industry to private investment and competition strengthens the country’s economy, at least over the longer term, while reducing government vulnerability to volatile oil prices. In the telecom sector, reforms are breaking up long-held private monopolies, and the financial system has been overhauled to strengthen competition and lower borrowing costs. Some of these reforms have already paid off handsomely and promise to deliver better results in the future. But Mexico’s presidents may serve only one term, and the race to succeed him in 2018 is wide open.

(Wall Street Journal, World Bank, Bloomberg)

2. Crime and Corruption

But a resilient economy isn’t everything. Corruption has long been a problem for Mexico, which ranks as the 95th least-corrupt country in the world. Some economists believe that endemic corruption costs the country anywhere from 2 to 10 percent of its GDP annually. It doesn’t help that renovations to Pena Nieto’s home have been tied to the awarding of government contracts.

Even worse has been the rise of crime, crystalized by the brutal murder of 43 students by drug gangs, which shocked the country and triggered nationwide protests. Mexico’s murder rate of 14 per 100,000 is nearly three times higher than in the US. Some 80,000 people have been killed in the Mexican drug wars, sometimes by cartels, sometimes by local police they’ve paid off. No one is immune to the violence. Over the past decade, nearly 100 mayors have been killed across the country. Mexico just had mid-term parliamentary elections this past June—seven candidates were murdered while another 20 were forced to drop out for fear of their safety.

(Transparency International, Financial Times, Reuters (a), Vox, New York Times, Reuters (b))

3. The Return

Against this backdrop (re)emerged Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the former mayor of Mexico City and two-time presidential runner-up. For years a member of the center-left PRD, Lopez Obrador vowed to take on the country’s entrenched political class. As mayor of Mexico City he made good on many of his promises, such as cutting the salaries of high-ranking public officials, including his own. He managed to finance much-needed infrastructure projects by cutting $2 billion from other areas of the budget and still provided significant welfare programs for the city’s elderly and disabled. While the city’s debt increased by one-third to pay for these programs, Lopez Obrador’s popularity soared.

Unfortunately, his 2006 presidential campaign was torpedoed by a bribery scandal involving members of his inner circle. Lopez Obrador lost that election by 0.55 percent to Felipe Calderon, but tarnished his national popularity by protesting the results for months on end. He still left his job as Mexico City’s mayor with an impressive 80 percent approval rating.

(Al Jazeera, New York Times (a), New York Times (b))

4. Morena

Lopez Obrador returned in 2012 to run against Pena Nieto, but lost that election by 6 percentage points. Following the loss, Lopez Obrador fell out with his party’s leadership, and broke away to form Morena, a further-left political party. The party’s success has centered on its anti-corruption and anti-establishment platform, a message that has understandably found resonance with the broader Mexican public. The party won 8 percent of the vote in its debut elections last June, and followed-up with a solid showing this weekend. Morena didn’t win any governorships outright, but its performance in key Mexican states such as Veracruz, where Morena received 26% of the vote—in an election where the winner captured just 34%—signal it’s now a political force to be reckoned with. In a simulation run this past spring, Lopez Obrador won the presidency in 11 of the 16 election scenarios analyzed.

But Lopez Obrador is also running on a fiercely anti-reform platform, and he has promised to undo many of Pena Nieto’s key reforms, bringing Mexico more in line with leftist Latin America. Lopez Obrador wants to undermine the one initiative that might change Mexico’s longer-term economic trajectory for the better, risking a return to deeper economic stagnation.

(CNN, Election Guide, LA Times, PanAm Post)

5. Mexico Still Positive…For Now

Yet, Mexico remains a good-news story for now. It’s the 12th largest export economy in the world, well-diversified and has free trade agreements with 46 countries. Over the past 10 years, Mexico’s GDP has grown more than 32 percent; ninety-five percent of Mexicans now belong to the global middle or upper class, according to the World Bank’s methodology. Even more impressively, Mexico’s growth pace is accelerating at a time when most of Latin America is slowing down. This fact is not lost on Mexican immigrants in the U.S. For the first time in more than 70 years, more Mexicans are now moving from the United States into Mexico than the other way around.

Problems remain of course, corruption and crime chief among them. But rather than taking these problems on directly, the populist firebrand hoping to win the presidency in 2018 has set his sights squarely on undoing the pro-market reforms that have delivered this recent success.

(World Politics Review, IMF, Council on Foreign Relations, Wall Street Journal)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com