J. K. Rowling has issued a plea to her fans not to spoil the plot of her new play, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. “You’ve been amazing for years at keeping Harry Potter secrets so you didn’t spoil the books for readers who came after you,” the novelist and newly-minted playwright said in a YouTube video. “So I’m asking you one more time to keep secrets and let audiences enjoy Cursed Child with all the surprises that we’ve built into the story.”

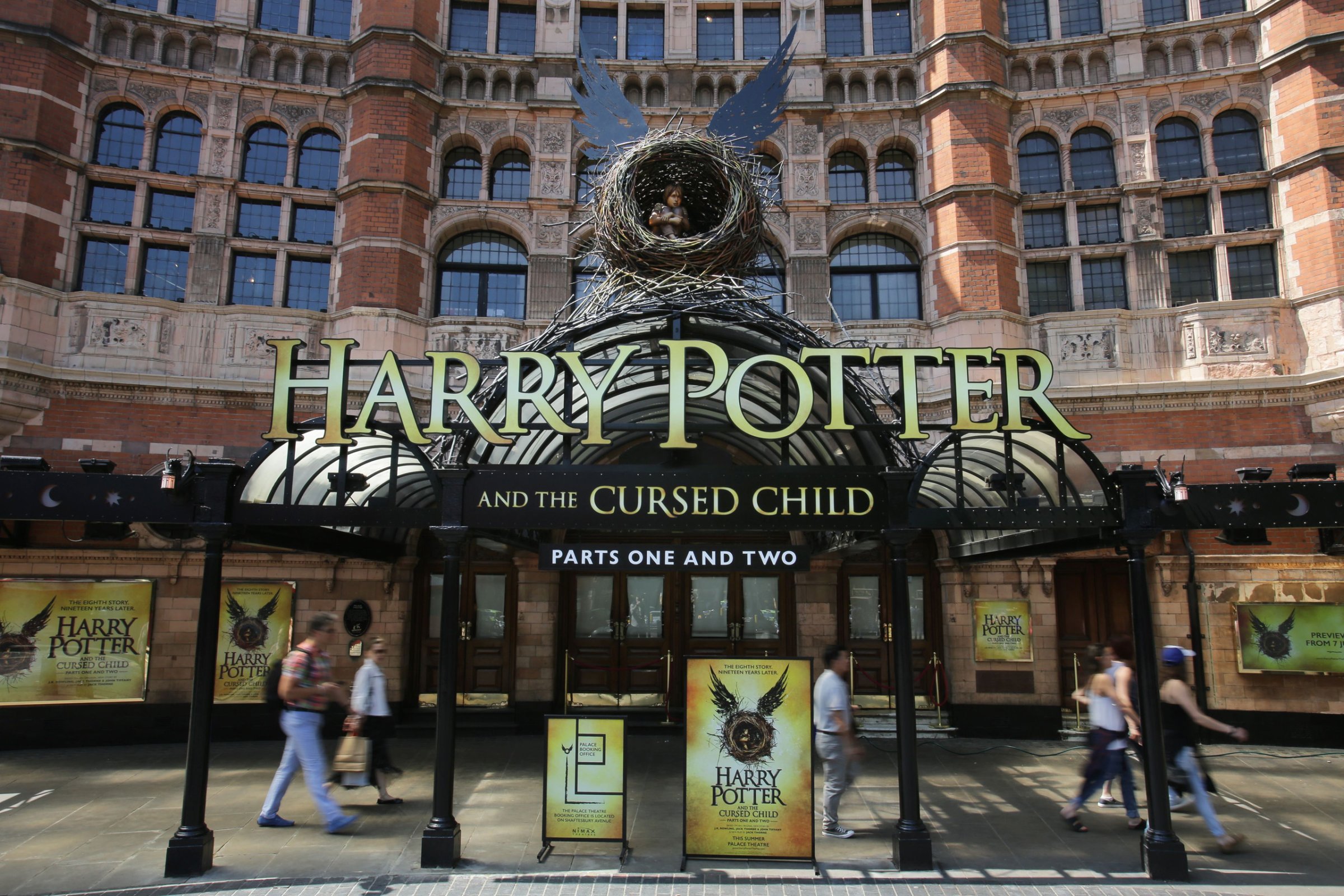

Rowling’s request is eminently reasonable—the play, which is to open in London next month, will be inaccessible to all but a select few fans. Though a book of the script is to be released, those who wish to experience the play as a play will have to get themselves to London and obtain a ticket that might be in higher demand even than Hamilton. And it has historical precedent: Miramax, for instance, specifically asked critics and moviegoers not to reveal that The Crying Game character Dil is a transgender woman, to name just one example. But it’s also wrongheaded. Within the very broad parameters of reason, people should feel free to discuss the art that they consume. If it’s good, the art will survive.

The question of when one is truly “spoiling” art—a movie, an episode of TV—has been litigated in the past, but evidently not to anyone’s satisfaction. (Telling people to avoid social media and relevant websites when they’re waiting to check out a popular work of art others have seen is well intentioned and will never, ever work.) Even the most anodyne writing about Game of Thrones on a Monday morning will get criticized for unduly revealing plot points; earlier in TV-criticism history, AMC and show creator Matthew Weiner requested that writers not even reveal the year that Mad Men episodes took place. Rowling’s directive seems to fall along similar lines: She doesn’t indicate what, exactly, is a “secret” to be kept, so therefore everything could be one. There’s little left to talk about, with such stringent guidelines, other than how good Game of Thrones, Mad Men, or Harry Potter and the Cursed Child is, which is exactly what the creator wants.

If her play is anything like her novels, Rowling has particular reason to fear spoilers. It’s apparent, in retrospect, that Rowling’s Harry Potter novels were reliant on the shock provided by one sort of twist in particular; her much-derided apologies to fans for “killing” characters seem like acknowledgments that death was an easy place for her to go to lend her narrative heft it didn’t consistently earn. If you know in advance which characters in the Potterverse die, their deaths seem programmatic and are perhaps less interesting. Similarly, the reveal of The Crying Game is one that’s been experienced by audience members who already know Dil’s secret: That the movie is really not much to write home about, but for its surprise.

By contrast, the lonely death of Lane Pryce on Mad Men (to name just one example of a major twist in the work of a spoiler-phobic creator) works as drama even if one has been told about it before watching it. The Sixth Sense is still engaging and moving even if you know Bruce Willis is a ghost. (Sorry! No, not sorry—it’s been nearly 20 years.) Art has the capacity to do more than viscerally surprise—it is, after all, made up of components other than just story—and art that does so can’t really be spoiled.

All sides but for the trolls can surely agree that going on Twitter and posting the end of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child just for fun is loutish behavior. But, within the context of a review or even a conversation, talking about Rowling’s play in all its particulars—even the surprises—is fair game. And eschewing talking about it out of an abundance of caution actually spoils the tradition of taking art seriously enough to engage with it. If it’s well cast, an artist’s spell can withstand far worse than a little foreknowledge.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com