When I first met Muhammad Ali, he was performing magic tricks on Hollywood Boulevard. I was a freshman at UCLA walking along the street with two of my school buddies when we saw him strolling with a small entourage, doing sleight-of-hand illusions for fans who came up to him. This was 1966 and Ali, only five years older than me, had already made his mark as the youngest ever heavyweight champion. The next year, he would be stripped of his title after announcing he would not submit to being drafted into the Army because “I ain’t got nothing against them Viet Cong” who “never called me nigger.” Half the world would chant his name in praise; the other half would sharpen pitchforks and light torches.

And here he was, casually walking down the street as if he hadn’t a care in the world, delighting people he didn’t even know with his magic. His magic wasn’t just the simple tricks he performed, but his ability to draw everyone’s attention to him, whether he was in a crowded room or on a busy boulevard. And once he had their attention, he never disappointed them. No matter how many people were around, he was the only one you looked at. He exuded confidence, a sense of purpose and an undeniable joy, as if he knew that he and the world made a pretty good pair.

Being a big fan, I shyly approached him to say hello. If he knew who I was, he didn’t let on. He was friendly and polite and charming—and then he was gone, moving down the street like a lazy breeze, a steady stream. A force of nature: gentle but unstoppable.

The three of us walked away jabbering giddily about how cool it was to have met the champ. But to me that meeting was much more than running into yet another celebrity in L.A. I’d admired Muhammad since I was 13, when he and Rafer Johnson won gold medals in the 1960 Olympics. Rafer dominated in the decathlon and Muhammad triumphed as a light heavyweight boxer. To me, they were the epitome of the skill, power and grace of the black athlete, and they inspired me to push myself harder.

Muhammad’s influence on me in those formative years, from when I was 13 to when I met him on Hollywood Boulevard, wasn’t just related to athletics. He had not only conquered the boxing world through his undeniable dominance in the ring, but he had mastered the art of self-promotion unlike anyone since P.T. Barnum, who once said, “Without promotion, something terrible happens … nothing!” Muhammad cannily ensured that something would happen by playing the court jester. He bragged relentlessly and shamelessly—and in verse! He riled up some white folk so much that they would pay anything to see this uppity young boy put back in his place.

That place, for blacks of the time, was wherever they were told. Sure, athletes and entertainers were invited to sit at the adult table, but for everyone else, the struggle was still in its infancy. Once at the table, opportunities for blacks opened up everywhere. So if you were smart and wanted to maintain a successful career, you kept your dark head down, mouth shut, and occasionally confirmed how grateful and blessed you felt.

Not Muhammad.

He was a fighter, whether in or out of the ring. In the ring, he was as much businessman as athlete. Out of the ring, he was a champion of justice—and a terrible businessman. His conversion to the Nation of Islam in 1964 would eventually lead to his being stripped of his heavyweight title in 1967, when he refused to submit to the draft during the Vietnam War citing religious grounds as well as the fact that “my conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people.” This caused him to be sentenced to prison for five years, fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years, his license to box being revoked in all states. (In 1971, his conviction was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in an 8-0 decision.) He didn’t fight for three years during his physical prime, when he could have earned millions of dollars, because he stood up for a principle. While I admired the athlete of action, it was the man of principle who was truly my role model.

The next time Muhammad and I met was at a lavish Los Angeles party mostly attended by college and professional athletes. Members of various UCLA and USC teams were there, as were some of the Dodgers. I saw Muhammad floating like a butterfly through the party, only he wasn’t stinging anyone like a bee—he was flirting with all the women and charming all the men. He was like a magnet moving through a crowd of needles.

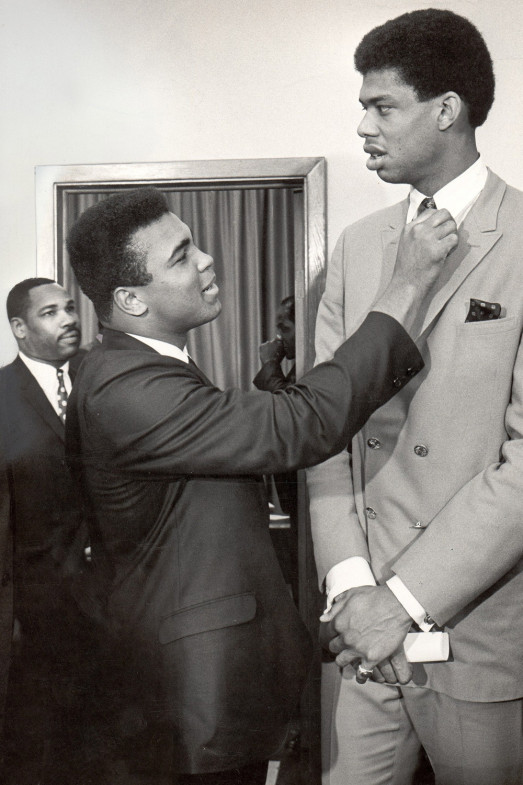

Like a typical gawky and insecure freshman, I drifted off on my own to check out the musical instruments the band had abandoned when they took a break. My dad was a jazz musician and brought me up around a lot of other musicians, so I had a passion for music even though I had no discernible talent. I started hitting the drums, working up a nice beat, when suddenly Muhammad Ali was next to me strumming a guitar. Muhammad’s personal photographer, Howard Bingham, immediately swooped in, posed us, and snapped an image of us jamming.

After that evening, Muhammad took on a big brother role in my life. He invited me to attend a meeting in Cleveland to discuss his protesting the draft. Basketball legend Bill Russell was there, along with NFL great Jim Brown and a lot of other Cleveland Browns players. In the early days of the draft, there wasn’t as much opposition to the war. People of color were among the first to protest, because it seemed as if we were the first to be drafted and sent to fight. Those too poor to afford college, which came with a student deferment, had little choice. As the draft extended to include more white, middle-class boys, opposition to the war grew in popularity. But despite our passion, we few athletes were unable to do anything significant to fight the draft. We left feeling powerless, especially knowing that had Muhammad allowed himself to be drafted, he would have never faced combat and would have still earned his millions. Instead, he would face the punishment for his convictions alone.

That’s when I realized he wasn’t just my big brother, but a big brother to all African Americans. He willingly stood up for us whenever and wherever bigotry or injustice arose, without regard for the personal cost. He was like an American version of the comic-book hero Black Panther.

Despite our mutual affection and respect, Muhammad and I were not always on the same path. While still a college student, I went to hear him speak in Harlem. Afterward, he took me to dinner to meet Louis Farrakhan, a leader within the Nation of Islam. I had been the object of enough recruitment dinners to know where this was going. Even though I had no intention of joining, my regard for Muhammad was so great that I chose to attend. However, my burgeoning involvement with Islam was strictly a spiritual quest, while the Nation of Islam seemed more of a political organization. I wanted to keep my pursuit of social justice separate from my pursuit of religious fulfillment.

Muhammad was not offended by my refusal to join. (In 1975, he left the Nation of Islam to embrace Sunni Islam.) Throughout the years we disagreed on other social and political issues, but none of that ever interfered with our friendship. We supported each other in the books we wrote, the charitable events we hosted and some of the causes we championed.

Most young people today know Muhammad Ali only as the hunched old man whose body shook ceaselessly from Parkinson’s. But I, and millions of other Americans black and white, remember him as the man whose mind and body once shook the world. We have been better off because of it.

Abdul-Jabbar is a six-time NBA champion and league Most Valuable Player. He is a TIME contributor and the author of the forthcoming book, Writings on the Wall: Searching for a New Equality Beyond Black and White.

For much more on Muhammad Ali, see TIME’s ALI: The Greatest, a 112-page, fully illustrated commemorative edition. Available at retailers and at AMAZON.COM

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com