When Cole Porter was born 125 years ago—on June 9, 1891—it was with a silver spoon in his mouth. But that didn’t mean the famed American composer and lyricist didn’t work hard for his success, too.

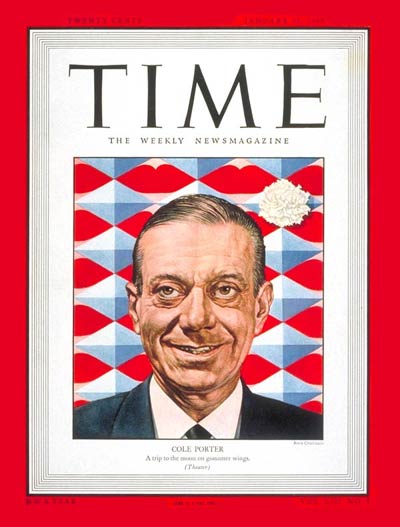

That balance, between the drive to work and the lack of a need to work, was largely the subject the 1949 cover story that TIME devoted to Porter as his latest show Kiss Me, Kate made a splash on Broadway. As the magazine put it, the two sides of Porter’s life were “show business and the high-living, high-gloss international society that lionized him long before his songs caught the public’s ear.”

That second side—that he was “born to wealth and bred to spend it”—proposed a problem for some publicists who worked with him. One person assigned by Warner Bros. to create a film biography of Porter told TIME that the idea flopped because there was no conflict in Porter’s story, at least nothing that they could turn into a feel-good narrative. His childhood as a coal and lumber heir, his years at the best schools, his “placid, childless, fashionable” marriage—with the exception of a tough recovery from an equestrian accident, all was well.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The drama had to be found, then, in the songs he created. There, his desire to always have the best was no less intense.

TIME explained just how, in detailing his working process:

While working on a show, he keeps his music and lyrics in neat sets of looseleaf notebooks and Manila folders, and he follows a chart of the book’s plot for spotting his songs. The only top-ranking Broadway composer besides Irving Berlin who writes his own lyrics, he usually begins with a song title to fit the plot situation, then finds his melody, and later fits the words to it. He begins with the last line and works backward. Close at hand is an exhaustive library of rhyming and foreign dictionaries (he speaks French, German, Spanish and Italian), geographical guides and other reference books.

When a Porter song is finished, it generally has a few added staves that are the germ of an orchestral arrangement. He writes out the lyrics in a neat, printlike hand, to be typed by his secretary. First to hear the music is Budapest-born Dr. Albert Sirmay, chief editor of Chappell & Co., Porter’s publishers, and also his musical secretary, friend and adviser for 22 years. While the composer plays the song on one of his baby grands, Dr. Sirmay jots down notes and sometimes warns him about cribbing inadvertently from the 400 songs (250 of them published) that Porter has already written.

Read the full story, here in the TIME Vault: The Professional Amateur

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com