“You are way too young!” Museum of Modern art curator Edward Steichen exclaimed as he was looking through Sabine Weiss’s portfolio in her tiny studio, without heat or running water, in a Paris courtyard in 1955. He ended up choosing three prints for his celebrated Family of Man show.

Unusual in her generation of European photographers, Weiss already had a strong reputation in the U.S. when Steichen visited her. The Swiss-born photographer had had several museum shows and her collaboration, through Charles Rado of the Rapho photo agency, with magazines such as Vogue, Life, Holiday, Town and Country, Food & Wine, The New York Times Magazine, and Esquire, had cemented her place in photography. Editors appreciated her boundless energy and her technical ability to cover a multitude of subjects, from fashion to music, advertising, children and food.

At 92, Weiss has been dubbed “The Last of the Humanists”, and even though she is getting tired of the label, she admits that it is somewhat fitting. The French school of photographic humanists, including Edouard Boubat, Robert Doisneau, Izis and Willy Ronis, flourished in France’s optimistic climate after World War II with a style, in black and white, that was a mixture of social realism and poetry.

Today, Weiss still lives and works in the studio she used to share with her husband, pop and surrealist painter Hugh Weiss, until the Philadelphia-born artist died in 2007. They had bought the 270-square-foot place and added a second floor where each of them had a studio. The walls are covered with paintings, mementos, objets trouvés, silver ex-votos, skulls, stones, icons…and the floors, with piles of tottering books. But even though Weiss is hard at work with her assistant, Laure, on last minute preparations for her upcoming retrospective at the Jeu de Paume–Château de Tours, which opens on June 18, not one photograph of hers is in sight.

The diminutive photographer with mischievous eyes and quick wit reigns, in the low light of a room where her tortoiseshell cat paces, as if owning the place, before settling on her sandal. “I think they must be made with fish glue,” Weiss wryly comments. Since she acquired her first camera at age eight, a cheap Bakelite camera, the photographer has been a fiercely independent spirit, recognizing no master. She has never liked schools, photographic or others, and thinks that the best things in her life happened through friendship or chance.

After running a successful studio in Geneva, Weiss fled town “because of an intractable love story.” She arrived in Paris in 1946, penniless, and for four years was an assistant to photographer Willy Maywald, learning about lighting and fashion. “I photographed with all sorts of cameras but always [came] back to the Nikon and Leica 24×36,” she says. Through her friendship with Doisneau, she joined the Rapho photo agency in 1952.

In the 1950s and 60s, Weiss was the rare woman in a male-dominated field; she recalls with amusement a time when photographers would elbow her and call out: “Hey, little lady, let the photographers work.” However, she avoids the “feminist” label as well.

“At the time, I had no interest in exhibiting my photographs,” she says. “My husband was the painter, he was the one who needed a gallery! Then in the 1970s a painter friend, Kijno, asked me to show my photographs in Arras. It was a shock for me to look at the pictures and see what I had done.”

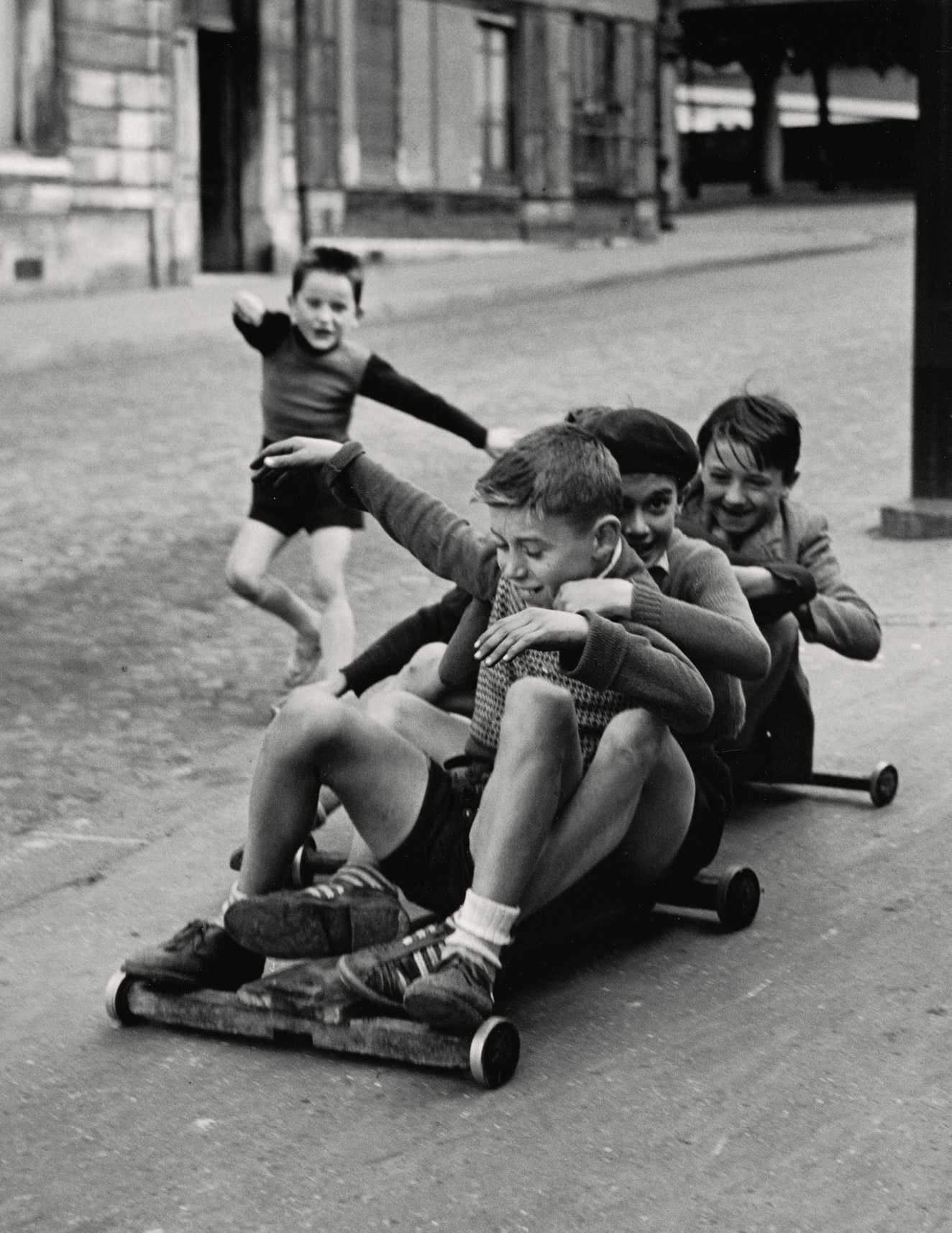

She had considered the prints she did “her private garden” but now realized that they were the core of her work. In contrast to her publicity work, where she had to stage images, she had photographed spontaneous scenes of everyday life, often in the vacant lots near the outer gates of Paris where poor children played with makeshift toys. One extraordinary image shows a child pretending to be a horse, galloping in the dust with a branch in his teeth as his friends run along, holding invisible reins. Another one shows a horse rearing up in a vacant lot, covered with snow.

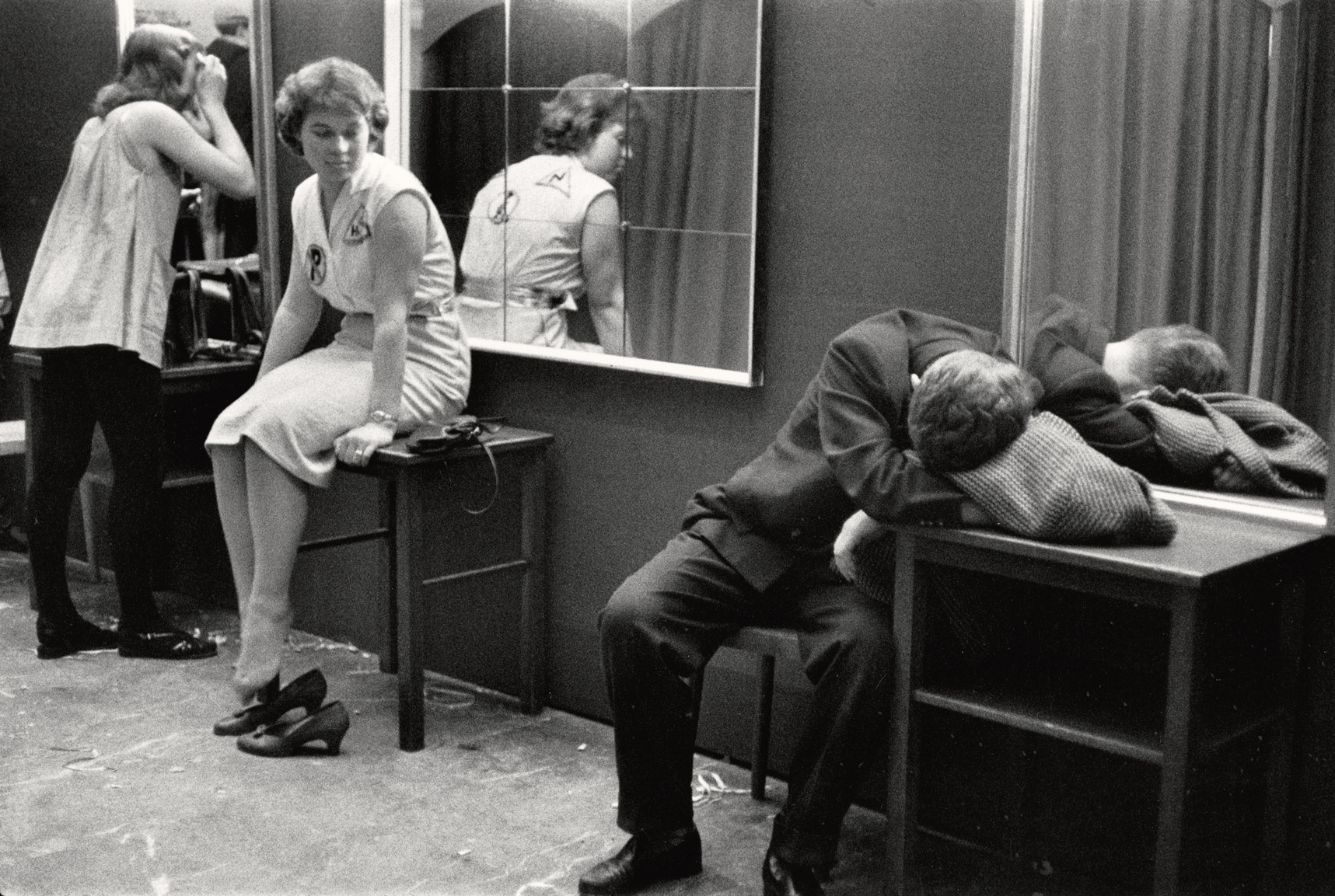

Weiss always avoids the anecdotal in favor of expressing emotion through subtle gestures and looks, eliciting a feeling of complicity with the subject. She often pairs children with older people, two faces of vulnerability. But even when she photographs the disadvantaged, as in a picture where a poor woman leans on a “Holiday On Ice” poster, she does it with a light touch and without a social agenda. “I do not like things that are too sensational,” she says. “But rather, sobriety. It is not about liking: you have to be moved. You have to go beyond anecdote, release the calyx, the contemplation. I would like to incorporate everything into an instant, so that the essential of human condition is expressed with minimal means.”

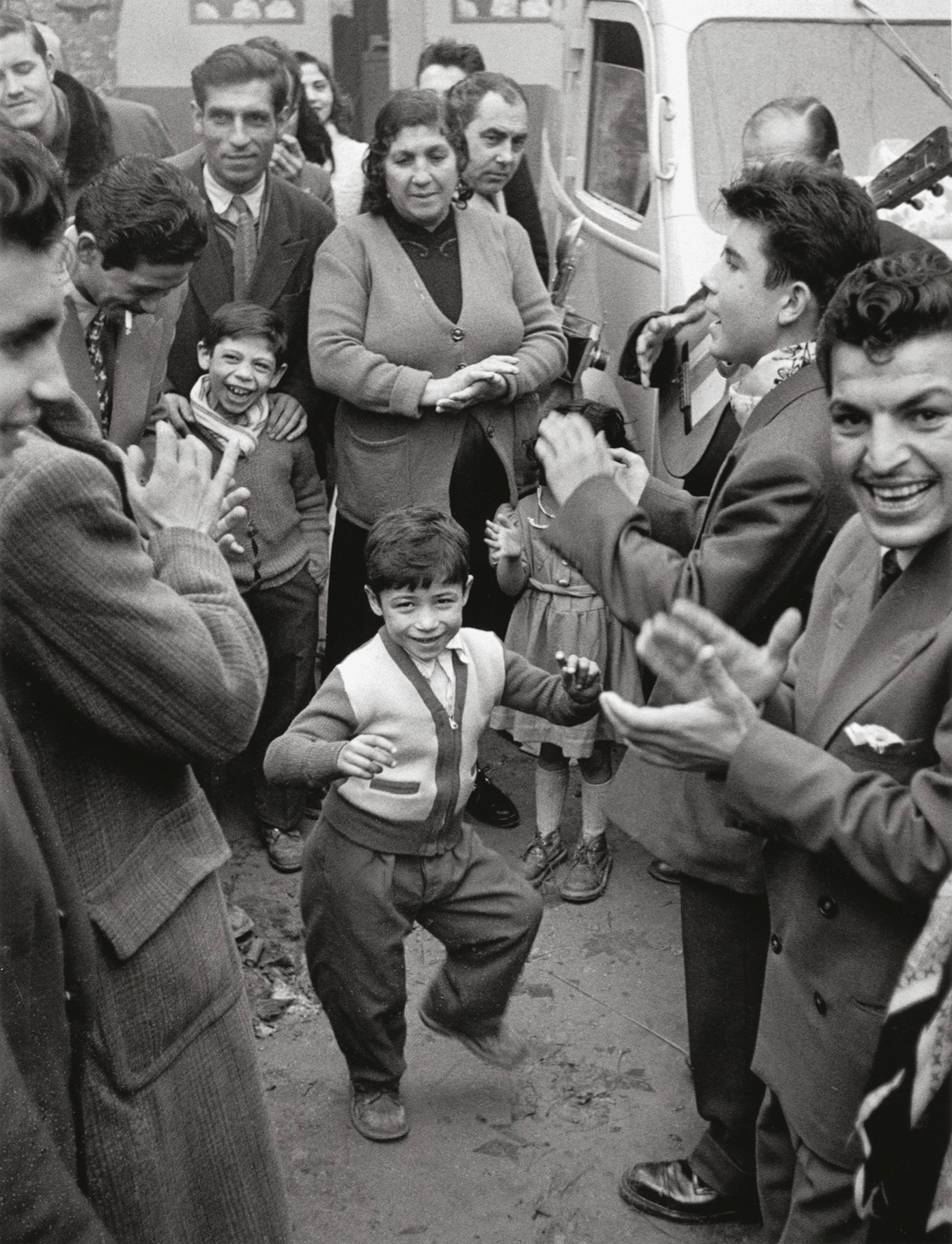

When she photographed a gypsy festival, she centered on a girl’s flamenco dance, not on the famous guitarist Manuel de Plata. Relegated to the back of the photograph, he takes a secondary role to the girl who whirls, absorbed in her moves. Weiss also made portraits of famous artists and writers, such as Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, and many others, but the portraits never look official, and the artists are most often captured while at work.

“I love to adapt to every one, the tramps and the great… The vacant lots where I photographed kids were full of mystery,” she says. “To interpret this mystery remains my passion.”

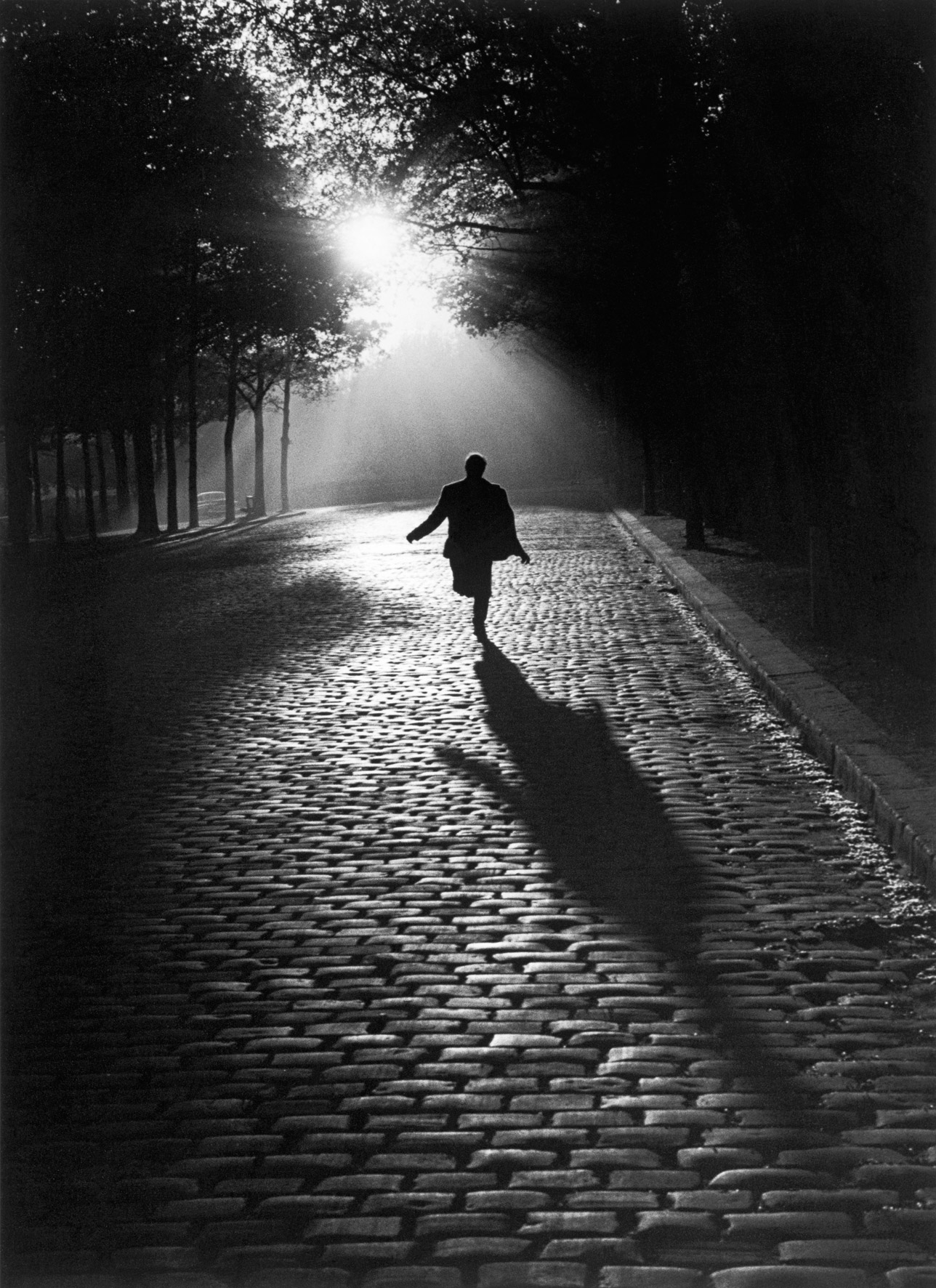

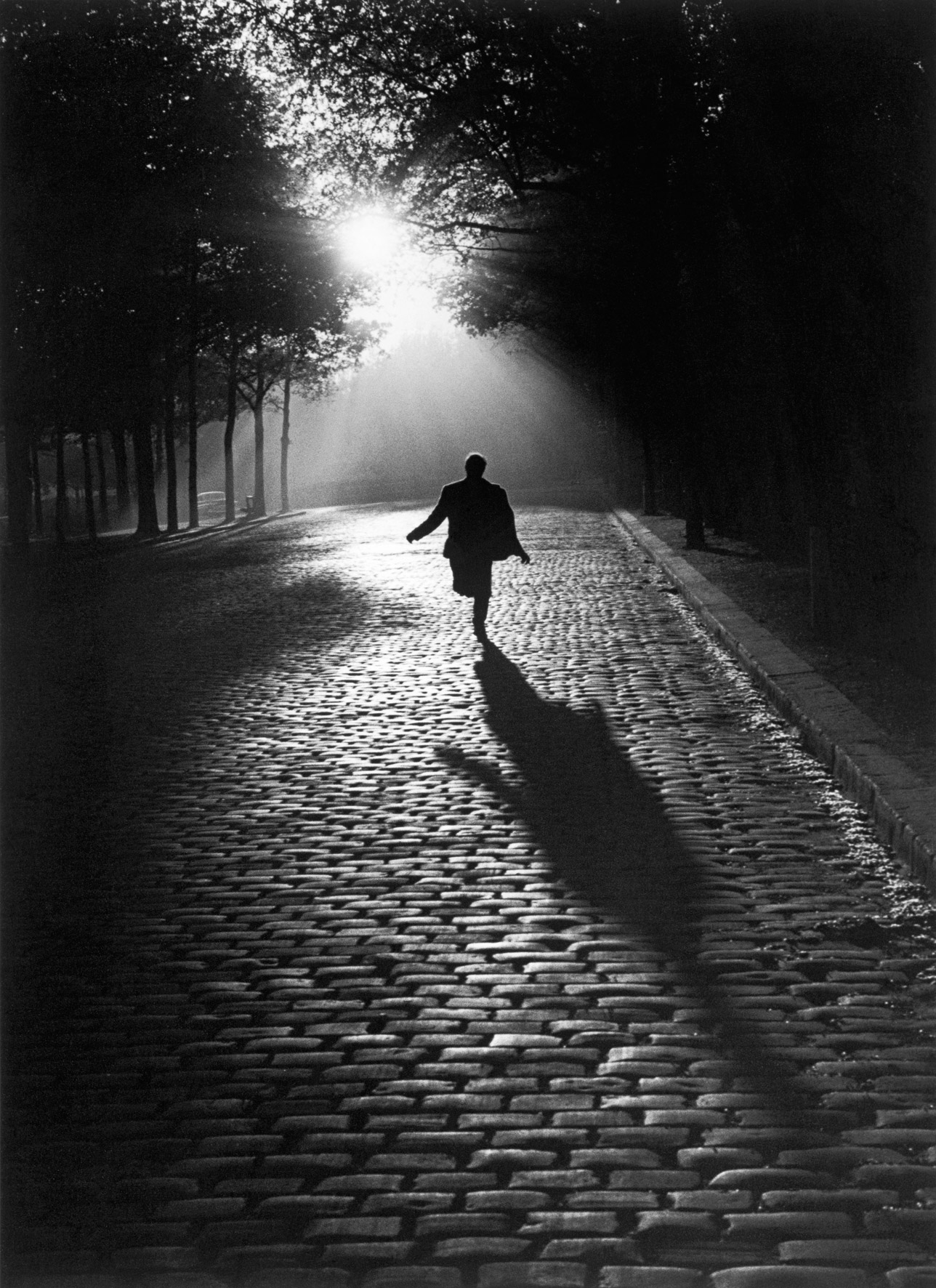

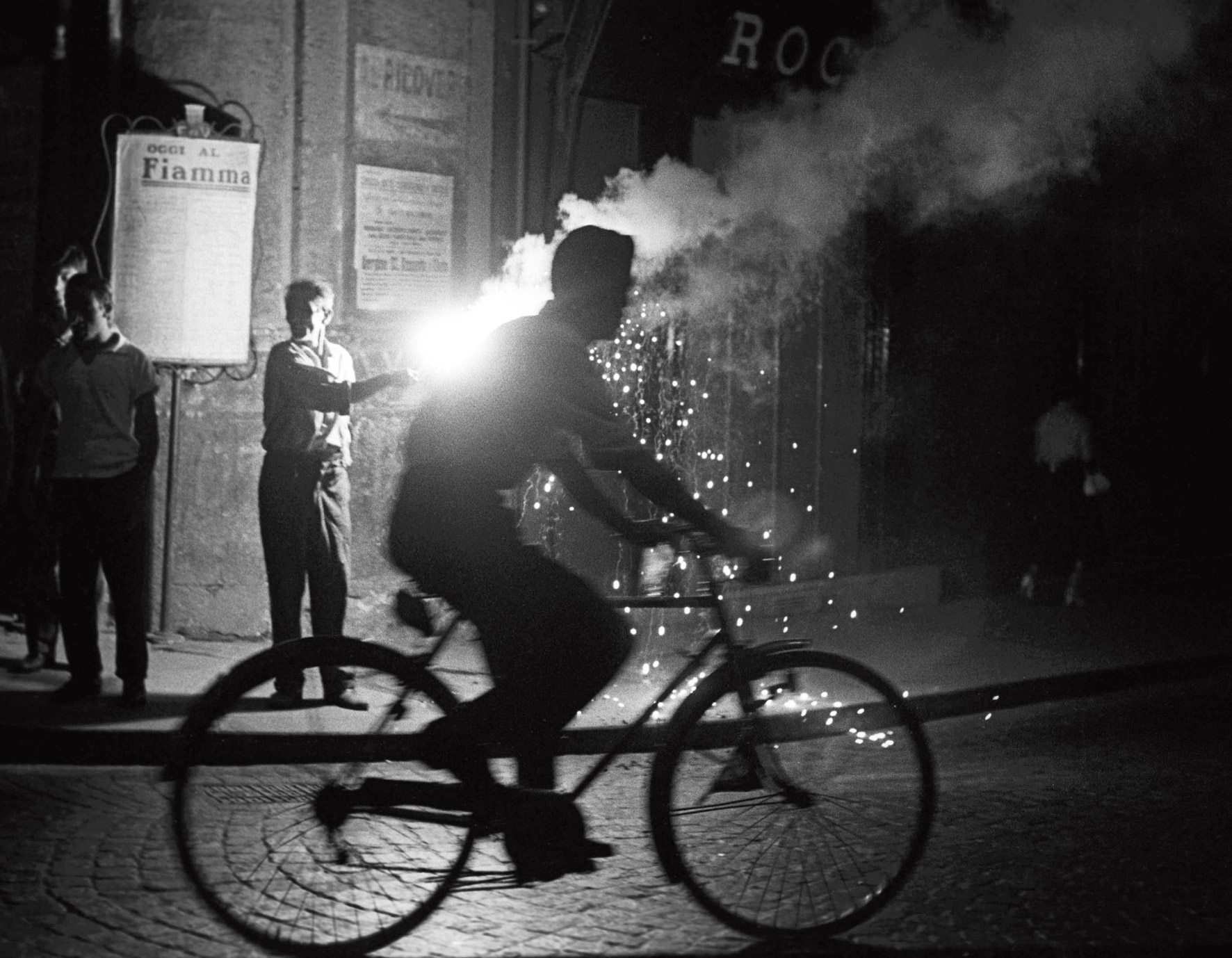

Weiss’ photographs have not aged because they retain that mystery and resist interpretation, maybe in part because they are taken in low light: she loves snow, rain, the moment of dusk, in Paris or Lyon, where the scene is illuminated only by street lights or car lights, the time when candles are lit in a church; she photographs shadows, reflections in a puddle, backlit figures and smoke. One of her most famous photographs shows a man running towards the light in a paved street, as if chased by his outsized shadow. “Under the Garigliano bridge, it is still there I believe, a small nameless street,” she says.

And, as I watch the crimson petals of a bouquet of peonies silently falling to the ground, Sabine adds, “I love mist, and I loathe sunshine.”

Sabine Weiss’ retrospective at Jeu de Paume-Château de Tours runs from June 18 to October 30,2016. In addition to 130 photographs, the show will include numerous period documents from her archives, many of which are being shown for the first time. Her exhibition at Les Douches-La Galerie in Paris runs until July 30, 2016

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com