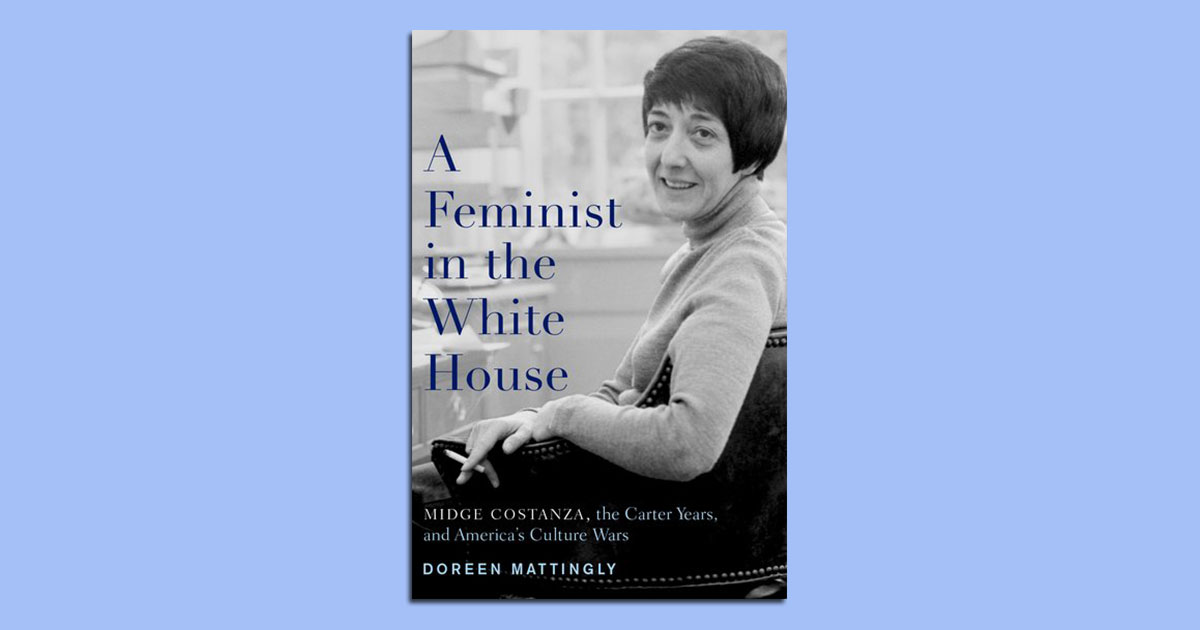

Equal pay for women. Gay rights. Access to abortion. These were some of the issues championed by the titular politician in Doreen Mattingly’s new book A Feminist in the White House. But that feminist is not Hillary Clinton in the 1990s—or, conceivably, the 2010s. It’s Midge Costanza, Jimmy Carter’s adviser on social issues and the first female assistant to a president.

Costanza’s path to the White House was unusual: a working-class Italian-American without a college education, she rose through the ranks of Democratic politics in Rochester, N.Y. In 1974, Carter helped campaign for her in an unsuccessful bid for Congress, “and they became fast friends,” Mattingly tells TIME. Carter was impressed with her street style and her strength in the community, and he turned to her for help in his presidential election. “She was able to deliver upstate New York for him, which was quite a feat because New York was not friendly to the Governor of Georgia in that race.”

She was rewarded with a spot in the administration—which also fulfilled his promise from the Democratic convention to appoint women. As Assistant to the President for Public Liaison (a job now done by Valerie Jarrett), Costanza’s job was to be Carter’s “window on America,” Mattingly says, to “bring the voices of disenfranchised people, particularly in groups, to him.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

And she did. “On domestic violence she really tried going through the system; on the issue of federal funding of abortion she pretty clearly spoke out against her boss; on the issue of gay rights she just kind of acted on her own,” Mattingly says, “and on the issue of the [Equal Rights Amendment] she kind of disobeyed what she’d been told to do,” pushing the president to stay committed to its passage. “She felt like Carter was committed to these issues, that’s what she believed, and she wanted to see him keep those promises.”

But she didn’t feel her efforts were paying off. It became clear to Costanza and her team that their voices were not being heard. That’s why the original title for Mattingly’s book was An Unwilling Token, the author says: the White House official was an outward symbol of the Carter administration’s inclusiveness, but she was—thanks to what she saw as resistance from others in the administration—unable to help others be included.

Everything unraveled for Costanza after she said she thought Bert Lance, the director of the Office of Management and Budget, should resign over questions of financial conflicts of interest. Shortly after, her staff was taken away and her desk was moved to the basement. She felt there was nothing left to do but resign.

Costanza went on to work in politics in San Diego, and she died in 2010 at 77. Mattingly credits a combination of sexism and classism with her downfall on the national stage. “I think that there’s still a real double-edged sword, particularly for women who are feminists, who say ‘Yeah, I think there’s something wrong with the conditions women experience and I’m trying to change them.’”

MORE: Read a 1977 story about Costanza, here in the TIME Vault

Mattingly says she believes that the same dynamic is playing out today in Hillary Clinton’s bid for the presidency. “[There’s a] notion that women’s issues are not serious issues,” she says. “So when you say, as I do, ‘I support Clinton, she’s been a leader on women’s issues,’ people say, ‘But what about real issues?’ Well for me they are real issues!”

Mattingly befriended Costanza later in life, and even promised to write this biography when Costanza was dying. She thinks her friend would have some advice for young Democrats watching the 2016 election: “If she were watching the political scene today, she would say to [Bernie] Sanders supporters, ‘O.K., now you’re interested in politics, but you don’t like the rules for the state party? Get involved, get active and change them.’ She had no interest in people who wanted to change things without participating in Democratic politics.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com