Go anywhere in South Sudan these days, and one of the most common building structures is use is a banged-up old shipping container. These 8-by-20-ft metal boxes, once used to transport goods across the ocean, now serve as homes, classrooms, play yards, medical clinics and even hotels. And according to a new report from Amnesty International, they are also increasingly being used as ad-hoc prisons for government detainees, where the poorly ventilated containers can easily turn into ovens in the baking heat.

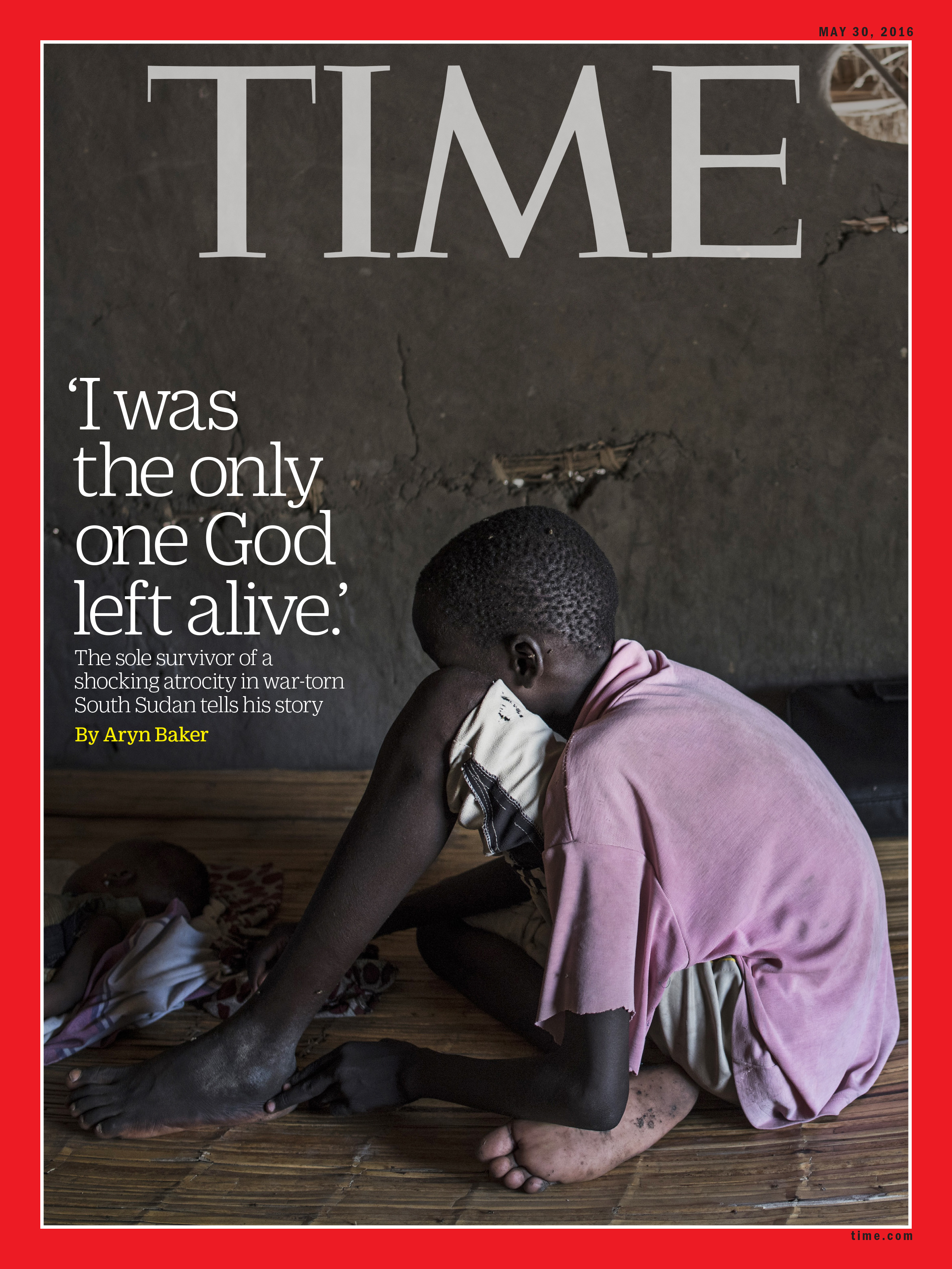

Read More: The Only One God Left Alive

The report details how dozens of detainees at one site near the capital, Juba, are locked together in a container, how they are fed only once or twice a week and how they are rarely given drinking water. The dire conditions, says Amnesty, have already resulted in several deaths. “Detainees are suffering in appalling conditions and their overall treatment is nothing short of torture,” said Muthoni Wanyeki, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East Africa, the Horn and the Great Lakes.

This is not the first time Amnesty has documented the use of shipping containers as prisons in South Sudan. In March they released a damning report about an October 2015 incident in which government forces asphyxiated more than 50 men by shutting them in a shipping container in Leer County, in October 2015. TIME met the sole survivor of the massacre, a 13-year-old boy, who spoke of his suffering in chilling detail.

Read More: Eyewitness to Hope and Hell in South Sudan

South Sudan’s military and presidential spokesmen denied the allegations, but the Leer County commissioner, Wol Yach, who was in Juba when the massacre occurred, admitted to TIME that the men, who were suspected to be rebels, may have been put into containers for detention purposes. “Maybe it was a mistake. Maybe the intention was not to kill them, but the soldiers didn’t know they were putting the men in a container without air.”

In their assessment of the Leer incident, the African Union-appointed body overseeing the country’s fragile ceasefire noted that the government had often used shipping containers as makeshift prisons. “The absence of [detention] facilities is a chronic problem,” in South Sudan, says Amnesty’s South Sudan researcher Elizabeth Deng. “But it is particularly egregious when this is done in secret or semi-secrecy by military intelligence or national security forces; when there is a very disturbing lack of concern for the health and well being of the detainees; and when the detainees are kept incommunicado, with no access to courts or to lawyers, and therefore no way to check whether they are alive or dead.”

Read More: War and Rape

Military spokesman Brig. Gen. Lul Ruai Koang was not able to comment on the Amnesty report, but he responded to a recent Human Rights Report describing horrific detention conditions and torture in the western town of Wau with an emailed statement: “The Report is bias, one sided and heavily relied on incredible eye witnesses to draw conclusions.”

Amnesty’s report includes a satellite image of what the organization believes to be the Gorom detention center outside of Juba. Four metal shipping containers can be seen in an L shape. According to Amnesty, the four containers are used to house detainees that arrived in early November 2015. Like the Leer detainees, most are civilians who have not been charged with any crimes, but are accused of supporting the rebel forces of opposition leader Riek Machar.

On April 26 Machar rejoined the South Sudanese government under an internationally brokered peace accord. Both sides are currently negotiating how they will work together in a government of national unity, but so far at least, the issue of illegal detentions, war crimes, and death in detention has not come up.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com