On Feb. 2, 2013, the Colorado state legislative leadership—Senate President John Morse and Speaker Mark Ferrandino—asked me if they would have my support for a bill that would limit high-capacity magazines. I said if the bill made sense and the votes were there, I would sign it—which is pretty much what I say when discussing any potential piece of legislation. I had already clearly stated that I wanted to pass a bill for universal background checks. Morse, a former Colorado law enforcement officer, wanted to propose a bill that would have held the manufacturer and the retailer civilly liable for any gun used in a crime. We had heard through the capitol grapevine that he had such a bill in mind. By then, we knew federal courts had already ruled that such laws were unconstitutional. Morse asked me if I’d support such a bill and I told him no for that very reason.

About a week later, Speaker Ferrandino’s House introduced three gun bills: One would make high-capacity magazines with more than ten rounds illegal, albeit with certain grandfather exceptions: if you already owned magazines with more than ten rounds, you wouldn’t be breaking the law. Another would make background checks mandatory for any gun sale or transfer. The third would require the customer to pay a fee for the background check. There were zero Republican legislators in support of the bills. To be fair, even some Democrats didn’t support them, at least as they were currently written.

During those days, and in particular, the day they were introduced, there were countless hearings and meetings going on surrounding the gun bills. There were many passionate Coloradans on both sides testifying at hearings and protesting around the capitol. A large number of the sheriffs of Colorado’s 64 counties came to protest the bills.

Generally speaking, these sheriffs, all of them elected in Republican counties, objected for the same reasons the Republican legislators objected. One of their arguments was that a high-capacity bill didn’t make sense and was unenforceable. They didn’t think it was practical or useful to arrest people with guns having magazines of more than ten rounds. They correctly pointed out that these magazines were still legal in other states and that anyone could order them for home delivery. As far as the background checks went, their main argument against it was that only law-abiding citizens would get the background checks; the bad guys wouldn’t bother. In other words, some sheriffs argued, the background checks wouldn’t do much, if anything, to prevent guns from getting into the hands of bad guys involved with gun-related crimes.

That same day, planes flew over the capitol with banners that said: HICK DON’T TAKE OUR GUNS. From around eight a.m. until late in the afternoon, a caravan of cars circled the capitol, honking horns and covered in signs protesting the bills.

That afternoon, in my office, I met with David Keene, then the president of the National Rifle Association. As you might guess, Keene was not too keen on the proposed legislation. With all the racket going on outside we had a hard time hearing each other, but as we talked, I tried to find middle ground. Keene agreed that mental health needed to be addressed. I guess you could say we agreed on the need to address mental health and agreed to disagree on the rest.

On February 12, about a week after the bills were first introduced, the House amended the high-capacity-magazine bill. Now the proposed ban was on magazines with more than fifteen rounds. The original ban on magazines with more than ten rounds was based on a federal law that had long since sunsetted. Drafters of this new amendment to the House bill made the change because many guns are manufactured with magazines holding ten to fifteen rounds. The thinking behind the change was that the bill might get more buy-in, or at least less resistance, if it didn’t attempt to make some of the most popular guns illegal.

The background check bill was also amended to include a provision that allowed a licensed gun owner to loan his or her gun to anyone at any time for a 72-hour period without needing a background check. In other words, if someone wanted to lend his friend a gun to go hunting, he could do so without needing to put his friend through a background check. The bill was also amended to allow family members to transfer their guns to extended family members, such as nieces, cousins, et cetera, without needing a background check.

As the session progressed and the debates over the bills became more intense, I thought about the objection to background checks raised by the sheriffs and Republican legislators. Maybe they were right; maybe background checks don’t snag bad guys.

I came home one night, tired and cranky, and made the mistake of complaining to my 11-year-old son Teddy. Sarcasm dripping, Teddy asked, “Daddy, what do you do all day at work that’s sooo hard? Make decisions? Dad, get the facts, make a decision, check, next.” He paused for effect, and repeated it: “Get the facts, make a decision, check, next. Every day I have to go into school and learn something that I didn’t even know existed the day before, and if I don’t get it completely right, my next day is misery, ’cause everything is based on the day before.” And he went on. After ten minutes, I had to agree that sixth grade was harder than being governor.

But when I woke up the next morning, I realized that he was right: we hadn’t gotten the facts. Republican legislators were united in saying that crooks weren’t stupid, they weren’t going to sign up for a background check, so why were we wasting the time and money of law-abiding citizens in a frivolous exercise? We had the national data, but we hadn’t asked for our local facts. We had been doing background checks on half the gun purchases, and we were arguing that we should expand that to all gun purchases. But we didn’t have results on those purchases that we did check.

So when I got to work, I called our office of public safety. What did we find in the previous year? Was it worth our time and the $10 fee we charged? Looking at the numbers from the previous year, 2012, when we were running background checks on roughly half of the gun purchases, here is what we found: In a state with a little more than 5 million people, we stopped 38 people who had been convicted of homicide from buying a gun. We stopped 133 people convicted of sexual assault, 680 burglars, and 1,100 people convicted of felony assault (where someone usually goes to the hospital) from buying a gun. And just in case you really don’t believe that crooks are stupid, we arrested 420 people, when they came back to pick up their new gun, on an outstanding warrant for a violent crime.

As far as the arguments I’d heard against banning high-capacity magazines, I could not ignore the connection between guns with high-capacity magazines and mass shootings.

One study charted 44 mass shootings between May 1981 and the December 2012 Sandy Hook tragedy—mass shootings meaning three or more people were killed—where the shooter used high-capacity magazines of thirteen rounds or more. In these mass shootings, 423 people were murdered, including two police officers, and 422 people were wounded.

It seemed to me there was ample evidence that background checks were worth the small fee and the ten-minute wait to do the check, and to support the high-capacity-magazine bill.

In early March, I received a call from Michael Bloomberg. He was irritated with us. Mayor Bloomberg was a staunch supporter of strict gun laws. With the fortune he had made in the news business, he was financing a national campaign to toughen gun laws. On the phone, he told me he felt that the House bills weren’t tough enough. He was concerned about the provision that allowed a gun owner 72 hours to share his gun with a family member or an extended family member without needing to undergo a background check. Once again, I guess you could say, we agreed to disagree.

Thus far, I had the sheriffs from Republican counties, the NRA, Mayor Bloomberg, Republican legislators, and even some Democratic ones upset with me. I figured we must be doing something right. Truth was, of course, there was a great deal of support for these bills. Mark Kelly, United States Navy captain, astronaut, and husband of Gabby Giffords, came to Colorado to testify in support of the bills.

All three of the bills moved from the House, where we picked up one Republican supporter, and through the Senate, where they passed, but without unanimous Democratic support.

I was scheduled to sign the bills on March 20, 2013. I fully expected that was going to be a difficult day for me politically. Then something happened that reminded me that a difficult political day really isn’t a difficult day at all.

The night before I was to sign the gun bills, a Tuesday night, I was at a dinner with a friend and local businessman, Rick Sapkin. Roxane White, my then chief of staff, called. We had a rule that whenever we called each other, no matter what, we would always take it. It was just after 8:30 p.m. She had a terrible tone in her voice: the emotionlessness of someone who is overcome with emotion and can’t let it get in the way. The first time Rox told me what had happened, I didn’t hear her. Rick and I were in a noisy restaurant. “What?!” I said. The second time I heard her loud and clear.

“It’s Tom. Tom Clements. He’s been shot. He’s dead.” It took a minute to sink in.

Tom Clements headed our state’s Department of Corrections. Shortly after I was elected governor, I hired Tom to come from his home state of Missouri, where he had run that state’s DOC. Tom had a reputation for being a progressive corrections director, who cared deeply about the mental health of his prisoners. He believed it was critical not to simply lock up criminals and then let them loose. For their own sake and for society’s sake, Tom’s guiding principle was to prepare prisoners for their ultimate transition back into society, which meant treating them as human beings.

Only a couple of days before Rox called and gave me the news that Tom had been killed, he and I had been in a meeting together. Even when Tom was talking about the most difficult things, he’d always make jokes and have a lighthearted tone. It’s been said that when someone dies, all the tears we shed are selfish tears because we feel bad about what we have lost from our lives. Tom changed the dynamic of our administration’s whole cabinet. Tom was someone who worked in a cold, hard world with a remarkably warm and tender heart.

The next day, Wednesday, March 20, I signed the three gun bills.

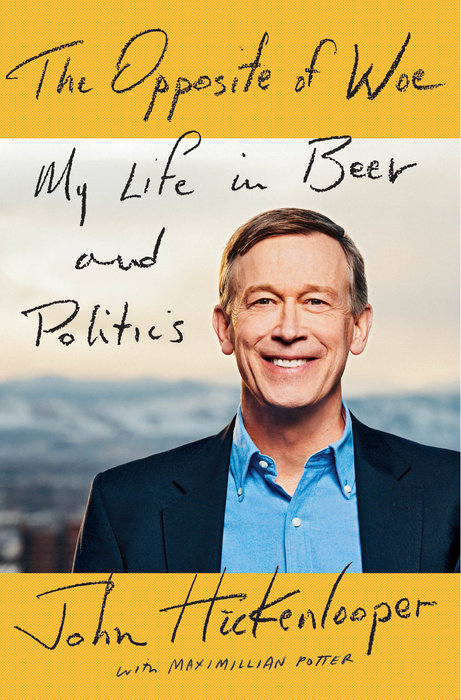

From THE OPPOSITE OF WOE: My Life in Beer and Politics by John Hickenlooper with Maximillian Potter, to be published this week by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright 2016 by John Hickenlooper.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com