We live in a time when science and technology are developing at warp speed. In his latest body of work, Thomas Struth asks us to consider what this rapid progress means for mankind.

His exhibition, Nature & Politics, draws together work taken between 2008 and 2013 from around the globe and encompasses wide fields of interest including technological systems, landscapes and museums. The title is intended as a “partly comical provocation,” says Struth, and pushes the viewer to examine complex constructs that are the product of human ambition. “Nothing that you see would be thinkable without nature but in everything you see, there is politics because there’s political strategies that impact you subconsciously,” Struth tells TIME.

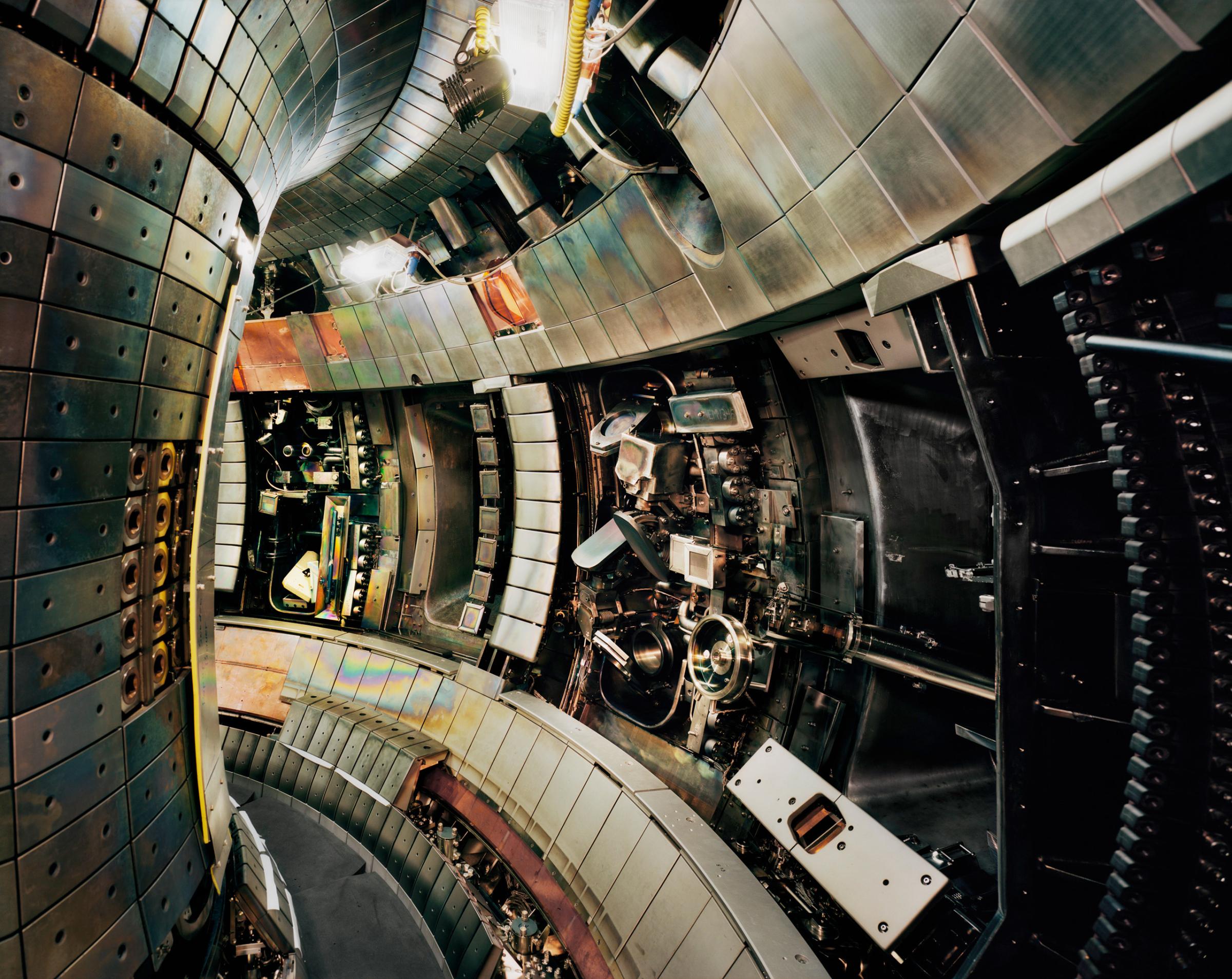

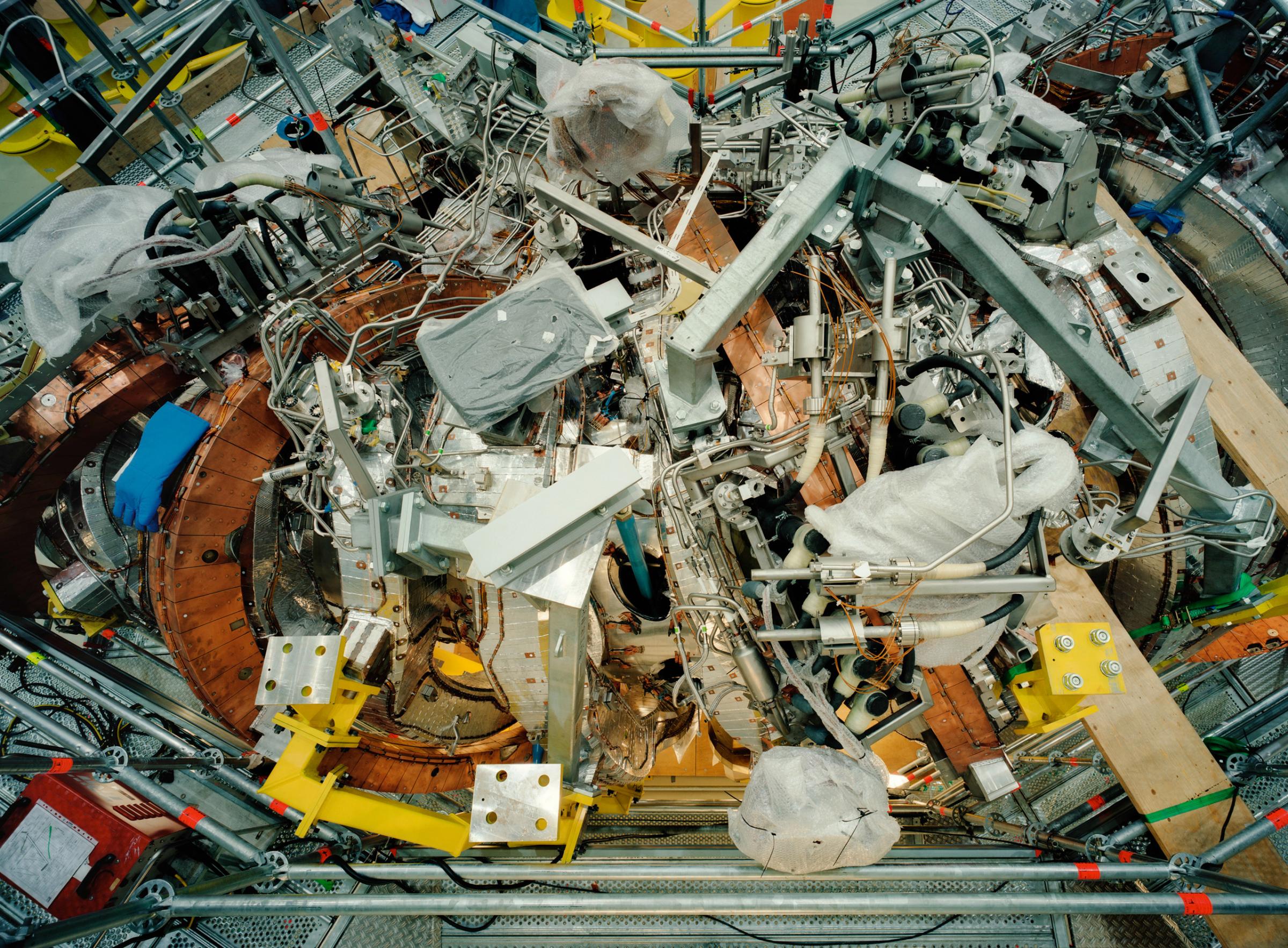

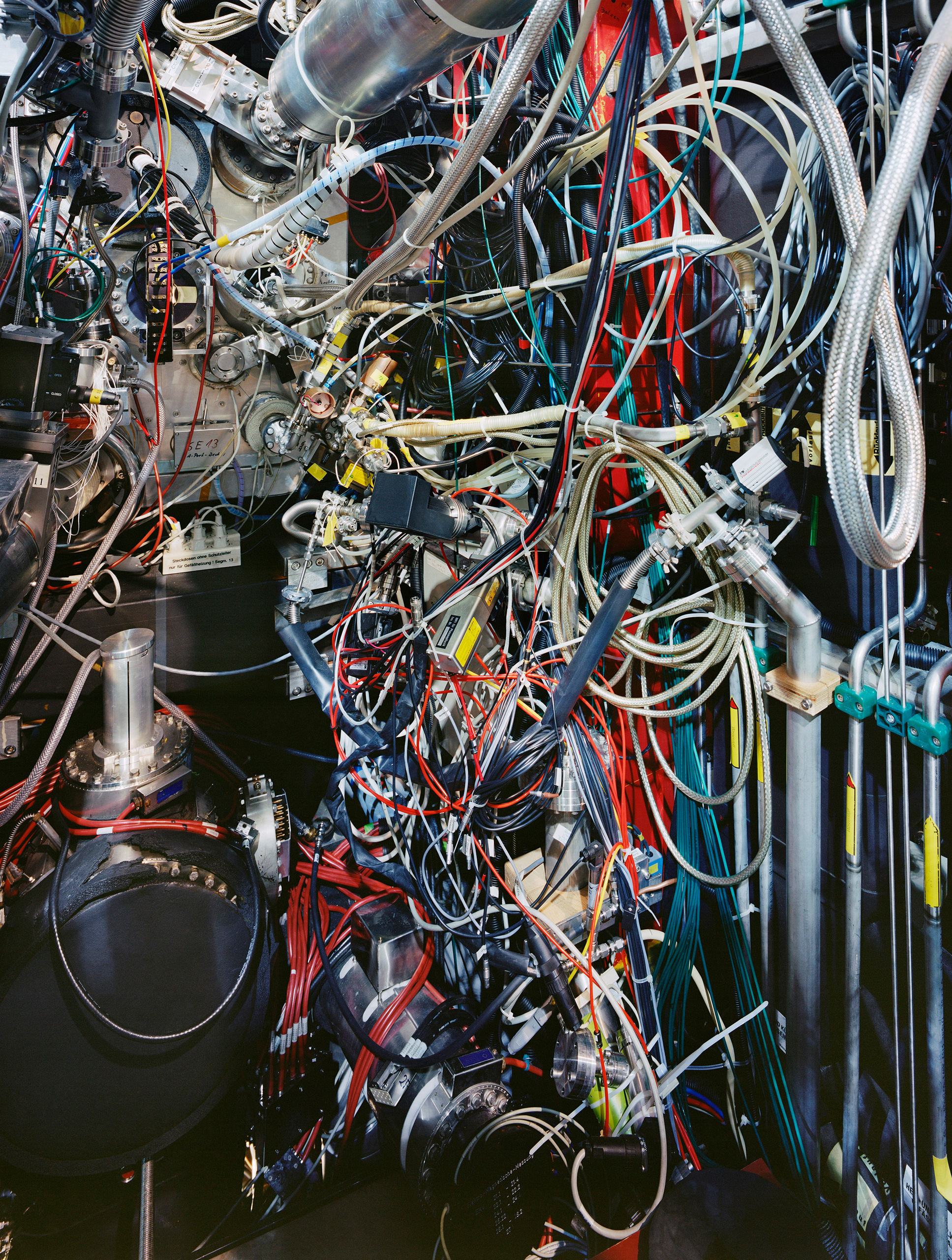

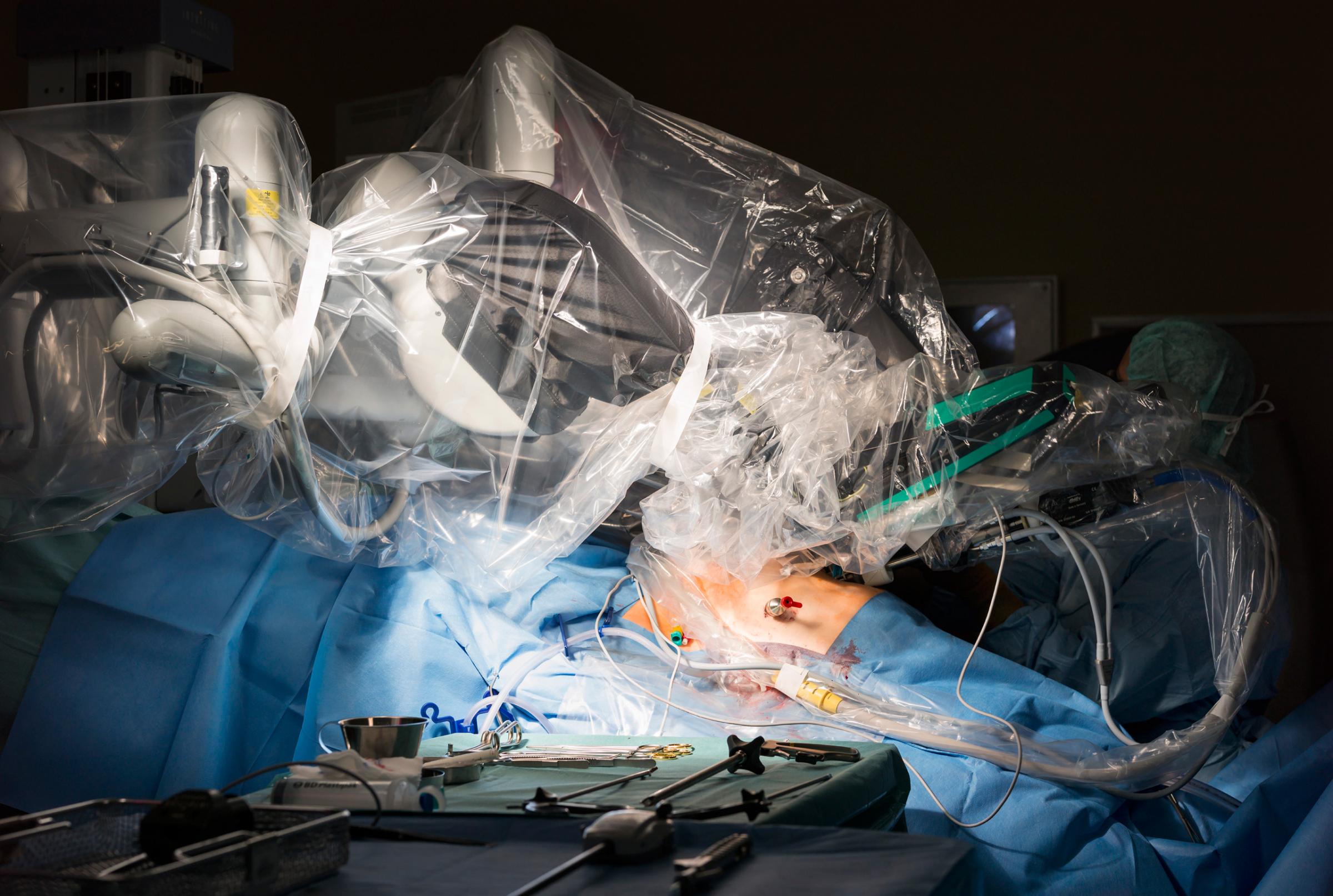

In his techno-scientific images, Struth pulls back the curtain on research spaces usually kept from public view. He suggests that these images may appear “daunting.” They could also be interpreted as sinister. The mass of wires, tubes, pipes, circuits and cables reveal the internal organs of technological systems and are deliberately esoteric. “Post 60s, technology has had an increasingly big affect on us, but it is also becoming increasingly invisible,” says Struth. “While on the other hand, technical images like television screens get increasingly sharp and close to what the eye can see.”

Struth emphasizes that this paradox is one that humans alone have fabricated: “It’s all created by us, not some aliens that came to earth.” These environments are as “wonderful” as they are “threatening” and the images allude to the notion that advancement can also be a covert means of control. “I’m not anti-science,” says Struth. “But once a door is opened it is very difficult to close it and say, ‘Okay, we don’t go there because it’s not ethically acceptable.'”

The artificial blurs with the natural, particularly in the portraits of a Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, Calif., where the oversaturated treatment emphasizes the fantasy world of manmade lagoons and canary yellow submarines. The park – the only one whose construction was directly overseen by Walt Disney – is the physical result of one man’s ambitious vision.

Meanwhile, Struth’s photographs taken in Israel and Palestine lay bare contested regions, where a different kind of ambition has manifested itself in conflict. Struth rarely shoots landscapes but in this region, the “so-called land and the territory is such an important thing.” But Struth says he didn’t want to fall into the trap of propaganda. “I wanted to express what I feel when I’m there but also keep it ambivalent and interesting so the viewer has to ask himself, what is this?” The photographs of the Middle East may seem at odds with the scientific images but for Struth, the subjects merge. Both religion – when it becomes “dogmatic” – and a belief in scientific progress are seen through a “tunnel vision of understanding”, says Struth.

In all his work, composition plays an important role, most certainly because of Struth’s background in painting. “I was very highly trained [in painting] and I take a lot of joy in questions of composition and light,” says Struth. “I always work with available light – I never light something artificially – so that might be moderated by my early experience and fascination with painting.” This direct style, along with the flatness of the camera angle, can mean the aesthetics of arrangement become as engaging as the subject itself. But it’s the photographs as a means of documentation, of scientific and sociological study, that is perhaps most compelling.

Thomas Struth is a German photographer based in Berlin. His touring exhibition Nature & Politics will be on show at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta from October 16 to January 8, 2017.

Myles Little, who edited this photo essay, is a senior photo editor at TIME.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com