The story of the Groveland Boys might not surprise anyone familiar with the miscarriages of justice that sometimes marked race relations in the early 20th century.

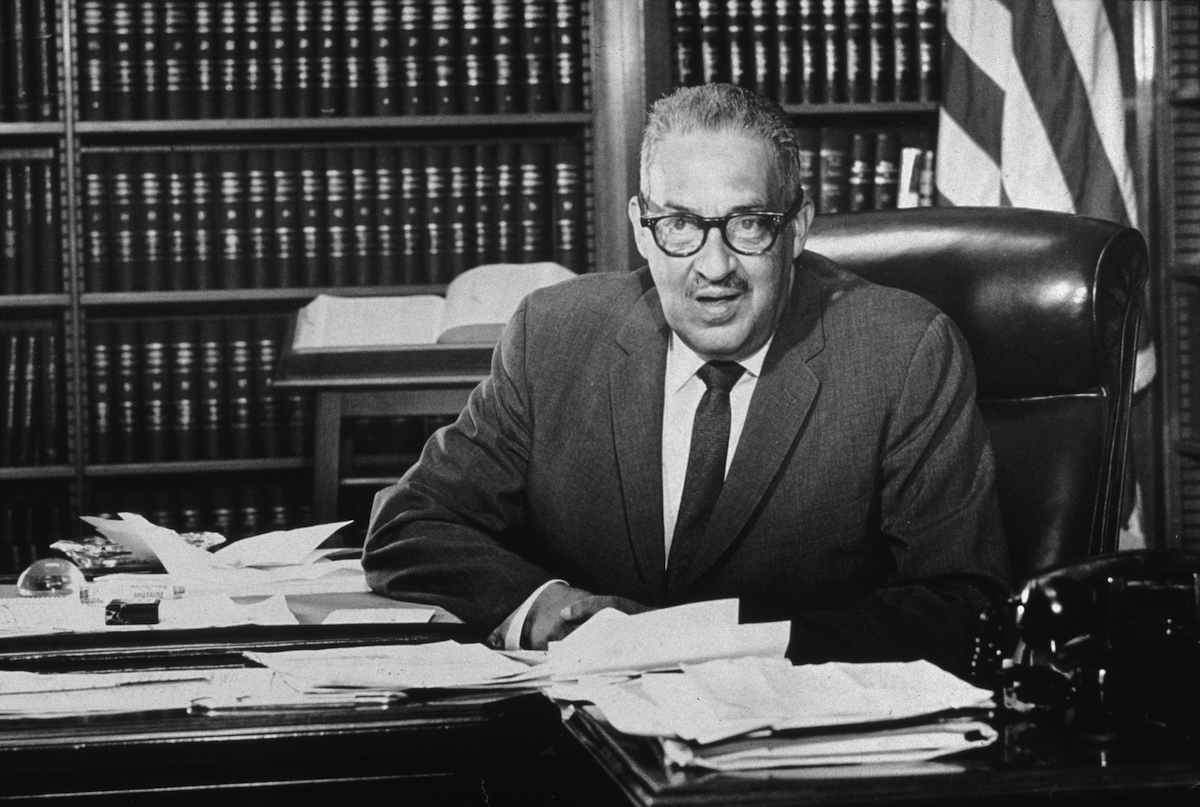

The case started in 1949, when four black men were accused of raping a white woman outside Groveland, Fla. One was killed by a mob a few days later, and the other three were tried and convicted. But thanks to Thurgood Marshall pursuing the case when he was executive director of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, the Supreme Court ordered a retrial.

Seven months after the Supreme Court decision, one of the men was killed and another injured in a shooting by the sheriff and a deputy from Lake County, where Groveland is located. The surviving two were convicted again, with one serving 19 years in jail and dying in 1970, two years after being released; the other was released in 1962 after 12 serving years and died in 2012.

Many believe the Groveland Boys were innocent, and today, city and county governments, the Florida Senate and concerned citizens are pushing for the state to apologize, exonerate and pardon the four.

In light of that effort, Gilbert King — author of the Pulitzer-Prize-winning Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America, which is being made into a movie — spoke to TIME about why the Groveland Boys case still matters today.

In the history of injustices in the U.S., what makes this case stand out?

What really makes this case stand out is it’s kind of like a To Kill a Mockingbird-type case or a Scottsboro Boys-type case, where you have these really explosive allegations, and then the dynamic in the community just gets a little out of control, seeking vengeance. So there’s a near lynching and then really a travesty of justice that follows, and ultimately, the Supreme Court overturned these verdicts. And then you had a sheriff in this Lake County that sort of took it upon himself to be the judge and jury.

So much has changed in terms of racial equality between 1949 and today. Describe Groveland and the surrounding area at the time.

You had these very powerful citrus people who really wanted a very strong sheriff in place to make sure that labor was kept in line, to make sure there was no organizing and union activity. So they really depended on a very strong sheriff to keep blacks in line [because they were] the labor in this community.

Almost seven decades have passed between then and now. Why does this case matter today?

Well, if you look back at this case, the doctor who examined the alleged victim in this case came up with a report that found no medical evidence to support her claims. And so the prosecution just hid [the doctor] from the defense. This witness was never able to testify, and the defense tried to subpoena him. But the judge overruled, saying it was irrelevant [because] we already have her word on what had happened to her. We don’t need medical evidence. … And so it’s still relevant because the families have never gotten closure on this. … And I don’t even know if closure’s the right word, but they do want some kind of exoneration or official pardon, posthumous pardon, on behalf of their family members.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

How certain are we that at least some of them are innocent?

I make that case in my book, I think, pretty convincingly. I’ve included the medical report that we never saw in the trial [and] the massive amounts of perjury that happened in this trial. … I’m absolutely convinced there’s no rape that took place. I studied this for many years.

Why is the state being targeted today for an apology, exoneration and pardons of the two who were later convicted, Walter Irvin and Charles Greenlee?

You have to do what’s called a posthumous pardon, and I think there’s only been one in the state of Florida. And that was for Jim Morrison of The Doors, believe it or not. … So this one’s a little more serious. I think [to the people leading the effort for an apology], the truth is sort of obvious, and they want this corrected because a lot of the Groveland families still live in Groveland or in Lake County. Before they pass on, they want to see justice done, and the only form of justice they can possibly get is a posthumous pardon or exoneration.

Will the apology, exoneration and pardons come eventually?

My thinking is it will happen. Eventually this will happen. … It still took eight decades to officially clear the Scottsboro boys. … Someone is going to have the courage or the fortitude to do what’s right, and ultimately, this will happen just like it happened with the Scottsboro boys. It’s just a matter of time.

Did we touch on everything that’s relevant now, or was there something that we missed?

I think it could be complicated because the alleged victim in this case is still alive. … I made an attempt [to talk with her] towards the end of the writing of my book. I went down, I found her in Georgia [but she has since moved back to Groveland], and I stood outside her door and had a conversation trying to persuade her to talk about this. And her message to me was: Let sleeping dogs lie.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com