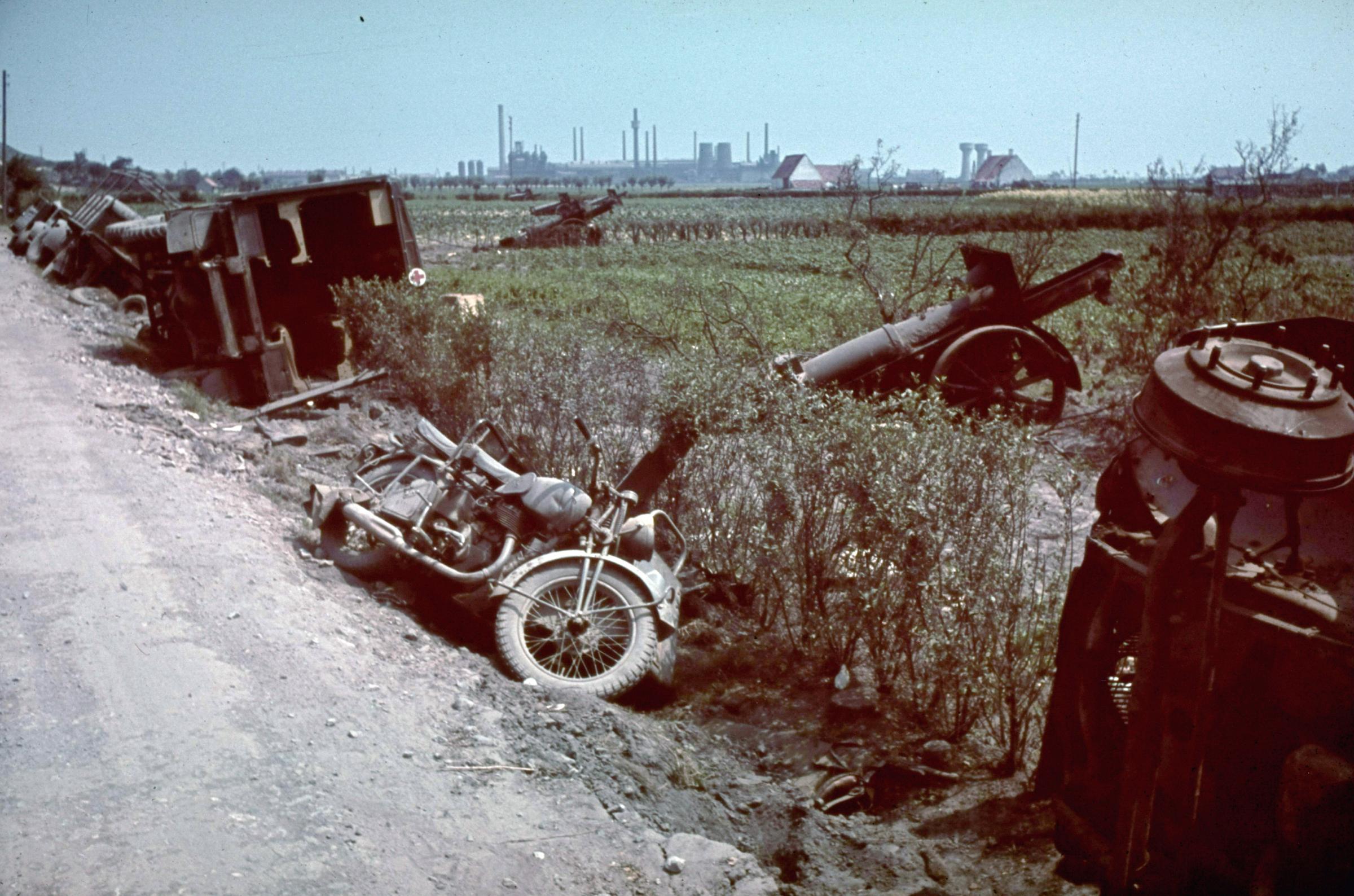

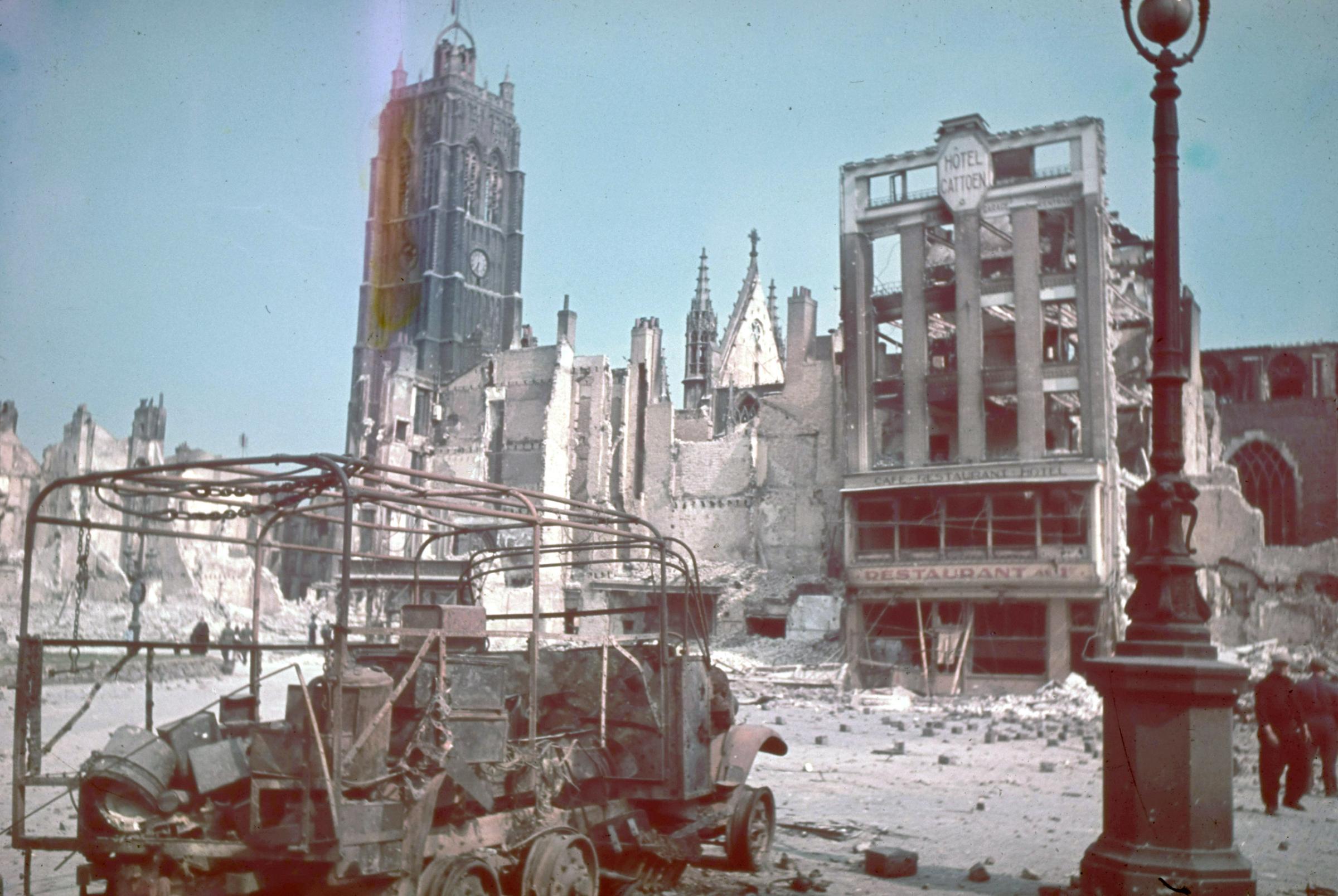

On May 26, 1940, the boats came for the Allies at Dunkirk. Over the course of a little more than a week, more than 330,000 troops had been evacuated from France, bound for England. The Germans were coming—they had moved through the Netherlands and Belgium that month—and had broken through the French defenses. Soon, they would reach the beleaguered Allied forces. Under cover of bombardment by the Royal Air Force, those forces managed to escape. But, though the aerial fighting helped those on the ground get out, it took its toll. Dunkirk was left, as LIFE’s reporter John Fisher cabled the magazine shortly after, “a pile of rubbish.”

“Every building was destroyed, not a wall intact,” he reported. “Bricks and stones, many feet deep, jammed the streets. Flames were still crackling and smoke swirled through the town as fires spread unchecked.”

At the harbor, “Frenchmen lay where they fell, their bodies bloated, legs and arms blown off, guts hanging out,” and refugees wandered the streets “dazedly.” Meanwhile, the German columns were already marching to the south, “looking for new battlefields.”

Sometime in that period, however, a man named Hugo Jaeger passed through Dunkirk. Jaeger was one of Hitler’s personal photographers, taking pictures for the Nazi leader’s records and enjoyment throughout the war. These images show Dunkirk after the Allies left, all rubble and refugees.

MORE: See More From the Hugo Jaeger Archives

How the photographs came to be part of LIFE’s collection is a fascinating story. As LIFE would explain in 1970, near the end of World War II, Jaeger worried that his photographs would be destroyed when Allied forces got to Munich. So he hid them, along with his last bottle of brandy, in a coal pile. When American soldiers did show up, they were distracted enough by the brandy and a put-and-take top that was in the bag that they never gave the pictures a second look. Jaeger was able to smuggle the slides to the countryside outside Munich and bury them underground, where they stayed until 1955 (he even drew a map to remember their location). At that point he brought them to Switzerland for safe storage.

In 1965, he sold Time Inc. the rights to 2,000 color negatives for $50,000. That archive contained these undated images of Dunkirk, which have never before been published by LIFE.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com