Now that Donald Trump is the presumptive Republican nominee for president, some members of his own party who opposed him are facing an unusual decision: What do you do when you disagree with your party’s nominee? Is it better to support him, in the name of party unity? To “denounce but not reject,” as the Atlantic put it back in December? Focus on down-ballot races? Wait and see?

Particularly for those who hope to run for national office on a Republican ticket in the future, the decisions they make about Trump now may have serious career consequences down the line. That’s just one lesson of the election of 1964.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

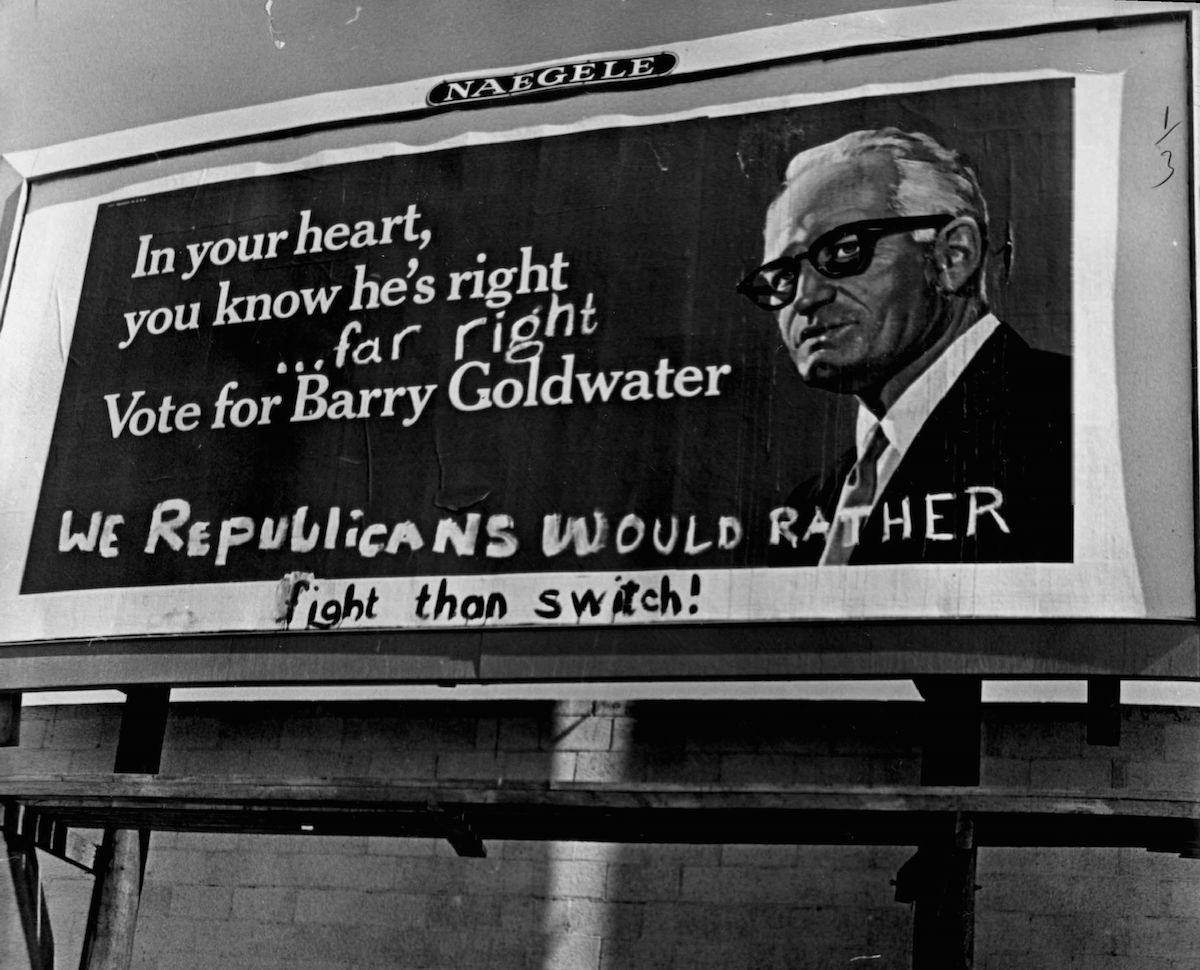

That year, the Republican party nominated the ultra-conservative Barry Goldwater, an Arizona Senator who would end up losing in a major landslide to incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson. The scales were already tipped against the party, as the country was still reeling from the assassination of popular Democratic President John F. Kennedy. But the nomination of a man the London Times called “so blatantly out of touch with reality, so wild in his foreign policy, so backward in his domestic ideas and so inconsistent in his thinking” that his nomination would be a “serious blow to American prestige” threw the party into further uproar.

Goldwater’s main rivals for the nomination, early in the race, were seen as Nelson Rockefeller, George Romney, William Scranton and James Rhodes. Richard Nixon’s name was also discussed.

MORE: See Barry Goldwater on the cover of TIME in 1964

Rockefeller’s reputation had been sorely damaged by a divorce and remarriage. In July of 1963, Rockefeller warned the party that it was “in real danger of subversion by a radical, well-financed and highly disciplined minority.” Goldwater was able to portray himself as the voice of party unity in response (something Trump is now trying too). Rockefeller fought hard throughout the primary season, pulling no punches in his attacks on his rival for the nomination. During the general election, Rockefeller said that he supported the Republican ticket but mostly abstained from public appearances outside New York, or even from mentioning Goldwater by name. Four years later, Rockefeller ran again, and again failed to get the nomination. As TIME pointed out back in 1968, “his failure to back Barry Goldwater in 1964 still rankle[s] among party workers.”

Romney refused to support Goldwater’s run in 1964, and Michigan Democrats even referred to Goldwater as an “albatross” around their governor’s neck. Romney succeeded in hanging onto the governor’s mansion but he, too, failed to secure the presidential nomination in 1968.

MORE: Watch History’s Most Infamous Political Ads

In July of 1963, Scranton had said that “the evidence against [the success of] a Goldwater candidacy is so devastating as to be incapable of complete error”—but that if Goldwater were nominated, he would “support him and work for him, whatever the long odds of his being elected.” After Goldwater cinched the nomination, Scranton didn’t quite follow through: he told crowds he would continue to fight to prevent the Republican party from becoming “some ultra-rightist society.” Even Ohio Governor Rhodes, who had eventually given his convention delegates to Goldwater, waited to see how his state’s Republicans would respond to Goldwater before he provided any significant support.

Having Goldwater on the ticket was also seen to hurt the chances of other Republicans, just by dint of association, and some down-ballot candidates decided it would be more in their favor to actively oppose the presidential nominee. Others up for reelection, like Maryland Senator J. Glenn Beall, took a halfway stand, asking Goldwater to clarify his positions. (Former president Dwight Eisenhower said in June of 1964—as President George W. Bush has said more recently—that he would not participate in any movement to push the nomination in one direction or the other.)

But not everybody was against Goldwater.

Richard Nixon, for example, publicly supported the idea that it was O.K. for people in the same party to disagree, which left room for Goldwater. And Ronald Reagan famously campaigned for Goldwater, with the speech that helped to launch not only his political career but also a new conservative movement.

They may not have been supporting the future president in 1964—but, perhaps not coincidentally, they ended up future presidents themselves.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com