As of Monday, the 69th edition of the Cannes Film Festival is almost exactly at midpoint, and already the pileup of terrific—or even flawed but fascinating—films is astonishing. If the first five or so days is any indication, this may be the strongest competition lineup in years. Cannes at this time of year is a place filled with professional complainers—in other words, critics—but if there’s any grousing to be heard at all, it’s simmering at a very low roar. For the most part, the mood around the Croisette is cheerful, though the lack of rain (generally a Cannes staple) certainly hasn’t hurt.

The first film to send critics here into communal rapture was German filmmaker Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann, a seemingly simple story about a practical-joker dad, Winifred (played by Austrian actor Peter Simonischek), who launches an unusual plan to loosen up his high-strung consultant daughter, Inès (Sandra Hüller). Winifred is a long- divorced and extremely rumpled music teacher living somewhere in provincial Germany, with an ancient and very tired dog as his only companion. His shaggy crop of grayish hair looks as if it hasn’t seen a comb since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Inès, working on a tense assignment in Bucharest, comes home for a birthday visit but barely has time for her father. She’s a woman who, sometimes even in her leisure hours, dresses in trim, dark, boyish suits and extremely high heels, her blond hair wound into a tight French twist. In fact, everything about Inès is wound tight, and it’s clear she has very little patience for Winifred, who’s so freewheeling you almost wonder how he can survive in the world.

When Winifred’s dog dies, he shows up in Bucharest, at Inès’s door, with a rolly suitcase in hand and a set of giant false choppers in his breast pocket. Those crazy fake teeth go wherever he does—he pops them in whenever there’s a moment of tension, but more often just because. The funny teeth are old news to Inès, and she grudgingly tolerates them—and Winifred—before sending both back home. Or so she thinks.

Toni Erdmann is a comedy (mostly) that runs for nearly three hours. What sane person makes a two-hour-and-40-minute comedy? But Ade—who won the Silver Bear in Berlin in 2009 for her romantic drama Everyone Else—is in control every instant, and the minutes fly by. (The picture has been picked up for distribution by Sony Pictures Classics.) To say Toni Erdmann is funny doesn’t even begin to capture the out-there texture of the jokes, and of the actors’ timing. When Winifred shows up in a disguise even more outlandish than his normal undergroomed state, posing as a life coach in order to shock and amuse his daughter’s hoity-toity friends and colleagues, she snaps at him: “Do you have plans in life other than slipping fart cushions under people?” Winifred replies, huffily, “I don’t have a fart cushion.” And then gets one, pronto.

His antics wear her out at first, and then they wear her down. Eventually, accord is reached in the quietest and most believable way possible—it sneaks up on the characters, and on us. In the course of this strange and marvelous father-daughter cat-and-mouse game, Ade spins out dozens of luminous, shimmering ideas that speak to the way most of us live, and might even challenge us to rethink how we see our parents and our children. How far, really, does the apple ever fall from the tree? Are the flaws we see in our parents sometimes really a kind of strength? In a world that never slows down, let alone stop, how do we keep our work from sapping our lifeblood? Ade can’t answer any of those questions definitively, but the faces of her actors—sometimes quizzical, sometimes annoyed, ultimately alive with the kind of relief that comes only from jettisoning the BS of modern life—guide the way. The radiance of Toni Erdmann is no joke.

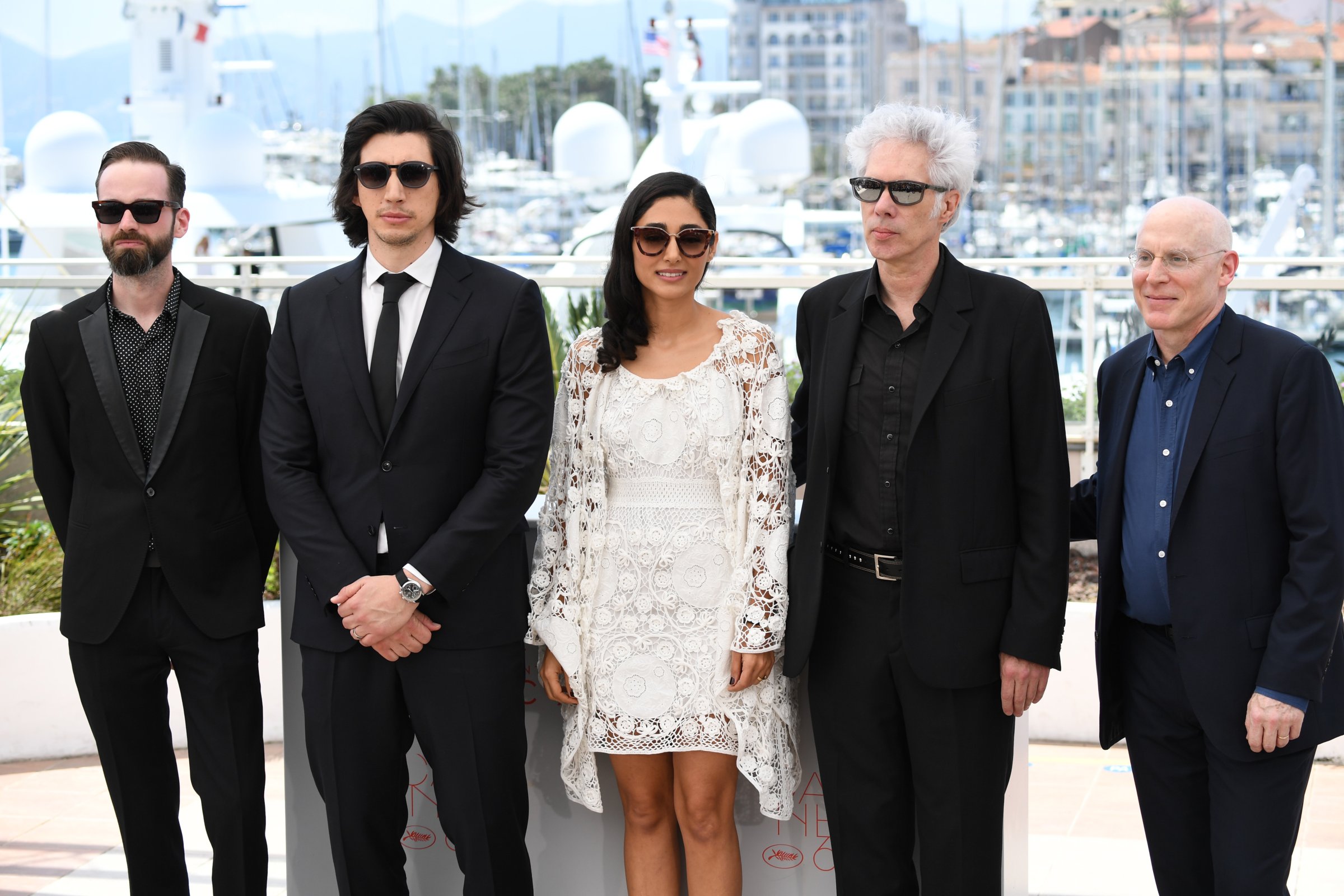

Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, also playing here in competition, is filled with another sort of light. It, too, is a joyous film, but it’s also brushed with melancholy shadows that cling. Almost a day after seeing it, I’m still thinking about it—and still laughing over some of its gently whirring wiffleball jokes—but also trying to parse its delicate, haiku-like beauty. Adam Driver plays a bus driver whose job is to navigate the streets of Paterson, N.J. He also happens to be named Paterson, and he’s lived in the city all his life. In the random spare slivers of his day, Paterson, quiet and thoughtful by nature, writes poetry. (His poems, as seen and heard in the film, were written by New York School poet Ron Padgett.) Anything can inspire him: A box of Ohio Blue Tip matches, his sense of the bus he drives pushing through air molecules. He catches scraps of conversation from his passengers—they don’t directly inform his poetry, but you get the sense they’re a subtle tapestry background for everything he thinks about and feels.

At the end of the day, he goes home to his wife, Laura (Golshifteh Farahani), whom he loves dearly, and to the couple’s crabby bulldog, Marvin, whom he tolerates. Laura is as exuberant as Paterson is quiet: He’s barely stepped through the door before she’s showing off the curtains she’s just made (the couple’s small home is a riot of DIY home decor, mostly in the black-and-white scheme Laura loves), or prattling on about the cupcake business she’s going to start, or articulating her dream of becoming a country-western star. (All she needs to do is buy a guitar. And then learn to play it.) But she adores her husband, and she loves his poetry, too: She urges him to share it with the world, even though he seems mostly to want to keep it only for himself.

Laura dreams big; Paterson is content to go from day to day, enjoying his routine of walking down to a local bar each evening to chat with his neighbors. But we can see there’s always some small sadness, or at least a wisp of confusion, tugging at him. Driver is turning out to be one of the finest actors of the moment, an understated star with a great, non-movie-star face. This is a wonderful performance: Driver conveys, with just the subtle flicker of an eye or the gentle curve of a smile, how much he enjoys the life of the city—it’s something he breathes in every day, like air.

This is also one of the most beautiful-looking films of the festival so far, even though it’s set, and was filmed, in a city that many may not think of as beautiful. Jarmusch and his cinematographer Frederick Elmes capture this place in all its cracked-sidewalk glory. As Paterson guides his giant boat of a bus through the city’s streets, he passes Rent-a-Centers and Footlockers, places we don’t usually see in movies unless the filmmaker is trying to make a statement about “urban” life, with all the color-line divisions those quotation marks imply. Paterson—the movie and the city—is a place where white people and people of color live together and think nothing of it, even though they may get on one another’s nerves at time, as people in all cities do. Jarmusch isn’t making a big pronouncement about that, which is just one of the reasons Paterson feels so fresh and unusual. It’s about so many things: The energy that keeps even an economically depressed city’s lifeblood thrumming, the closeness but also the inherent loneliness of couplehood, the way the things we do in our spare time can come to define who we are. It’s about love and poetry and dreams, and about the chance encounter that can close a wound with the magic efficiency of a tiny butterfly bandage. How you pour all of that into one movie is something of a mystery—but then, a good poem is always something of a mystery too.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com