The U.S. may be home to the oldest national park—Yellowstone became the world’s first in 1872—but Canada can lay claim to the oldest national parks system in the world.

The Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act received royal assent 105 years ago on May 19, 1911, marking the beginning of Canada’s new setup, while the U.S. National Parks System was only created five years later, in 1916. The act created a new Dominion Parks Branch—now known as Parks Canada—that began its operation the same year, overseeing a handful of parks with a budget of $200,000 and seven employees. As in the U.S., the first land reserved for parks had predated centralized administration. Banff National Park got its start when land was set aside in 1885, and two years later the Rocky Mountains Parks Act made it Canada’s first national park.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Though the conservation movement was gaining ground at the time, the creation of the Dominion Parks Branch was more about what historian Claire Campbell has called a “minor bureaucratic shuffle” than about any grand goals for preserving nature. Administration of the existing parks had been transferred to the Forestry superintendent in 1908, but the number of people making use of the parks was increasing such that they needed their own governance. The new centralized management could do just that—though the act didn’t give much in the way of specific instructions. (The head of the new parks system, James B. Harkin, admitted he knew nothing of parks, and wrote to the U.S. Department of Interior for advice, as described by historian Alan MacEachern.)

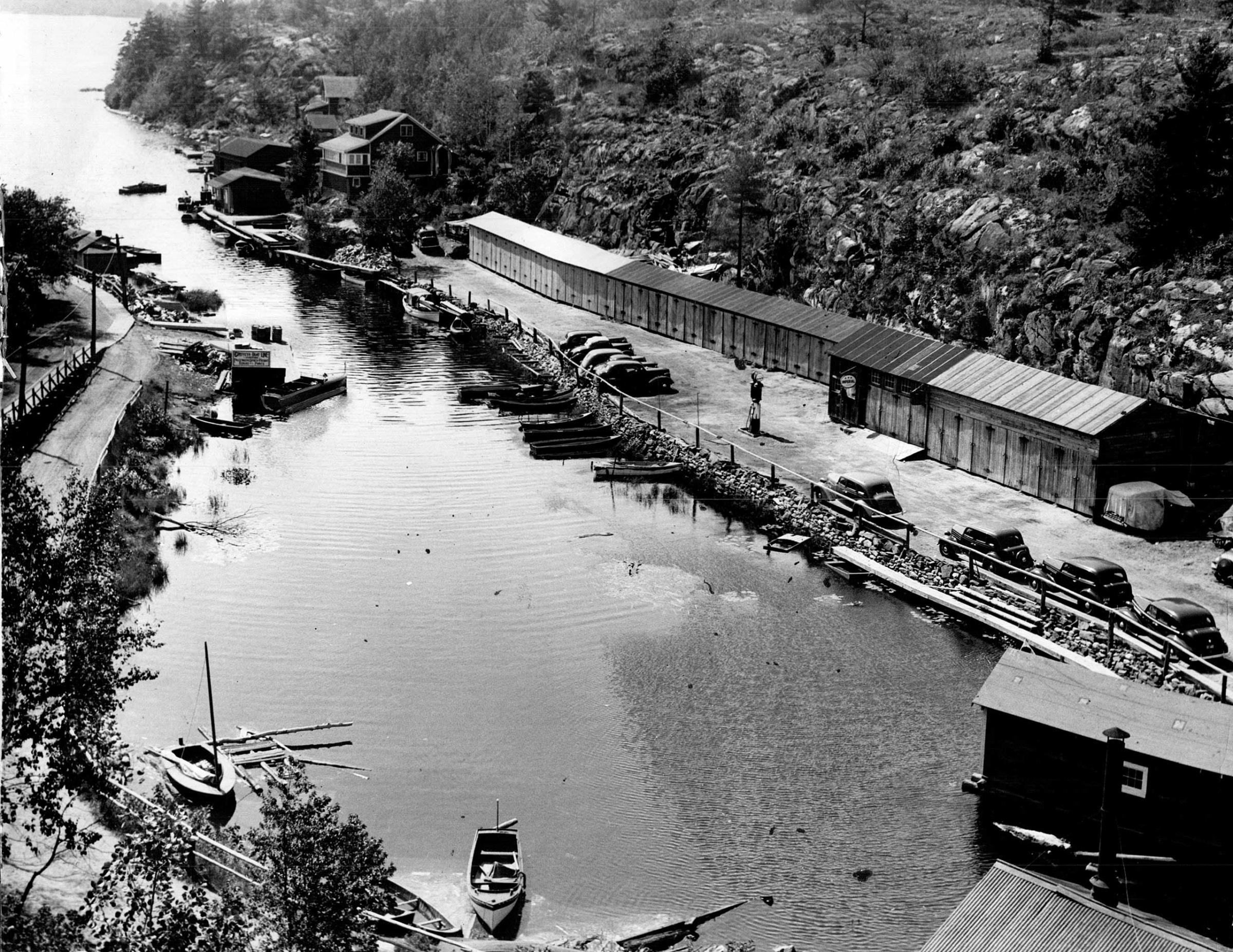

In fact, political discussions of the 1911 act focused on the timber in the forest reserves more than the parks themselves. It allowed loggers and miners to continue operations within the parks, and even recreational usage—which would lure tourists and their money—was intended to be more along the lines of hunting and fishing than gazing out at the surroundings in awe. “National parks were not imagined as a way of preserving nature from people,” Campbell writes, rather “reserving nature for the people’s use.”

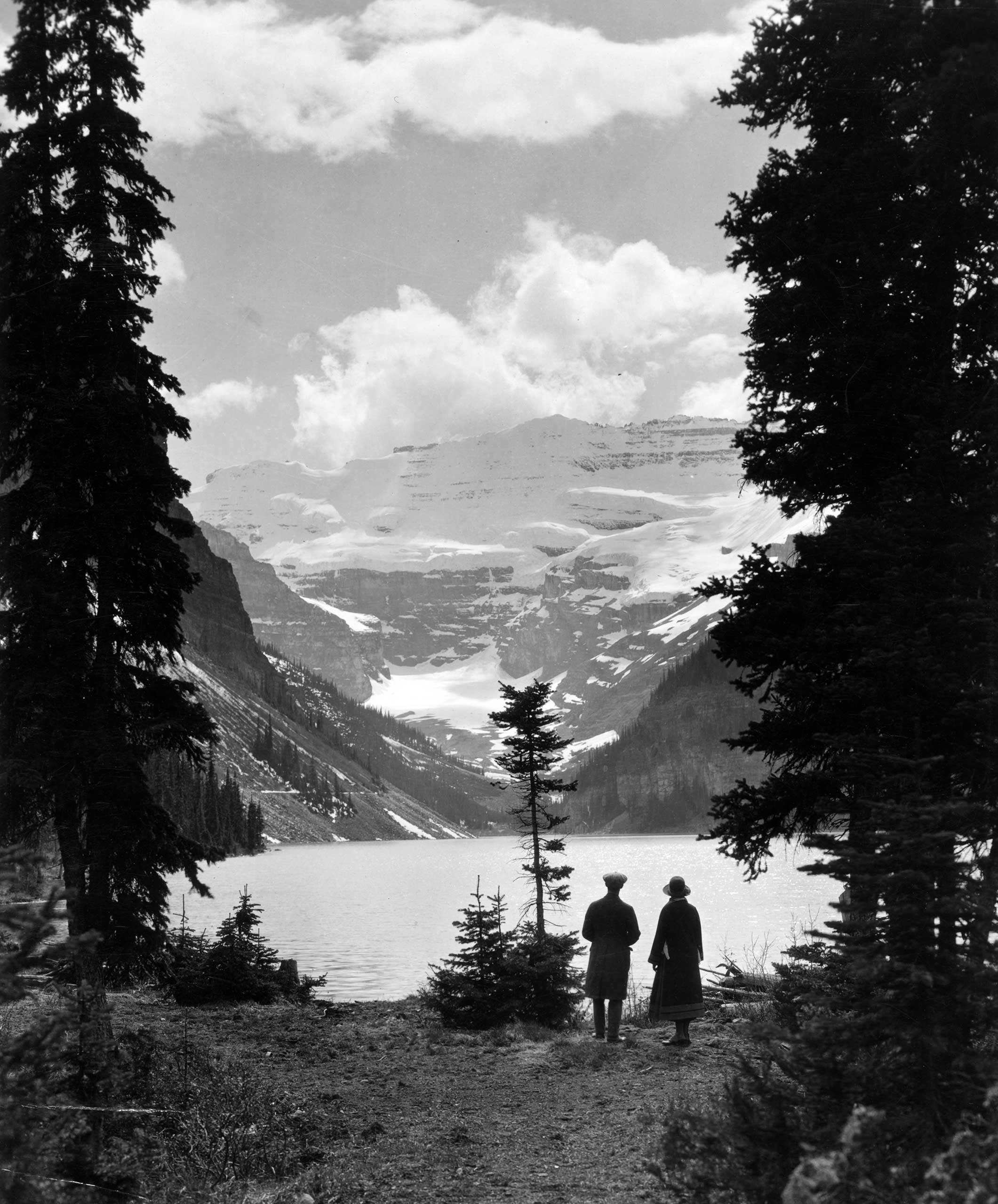

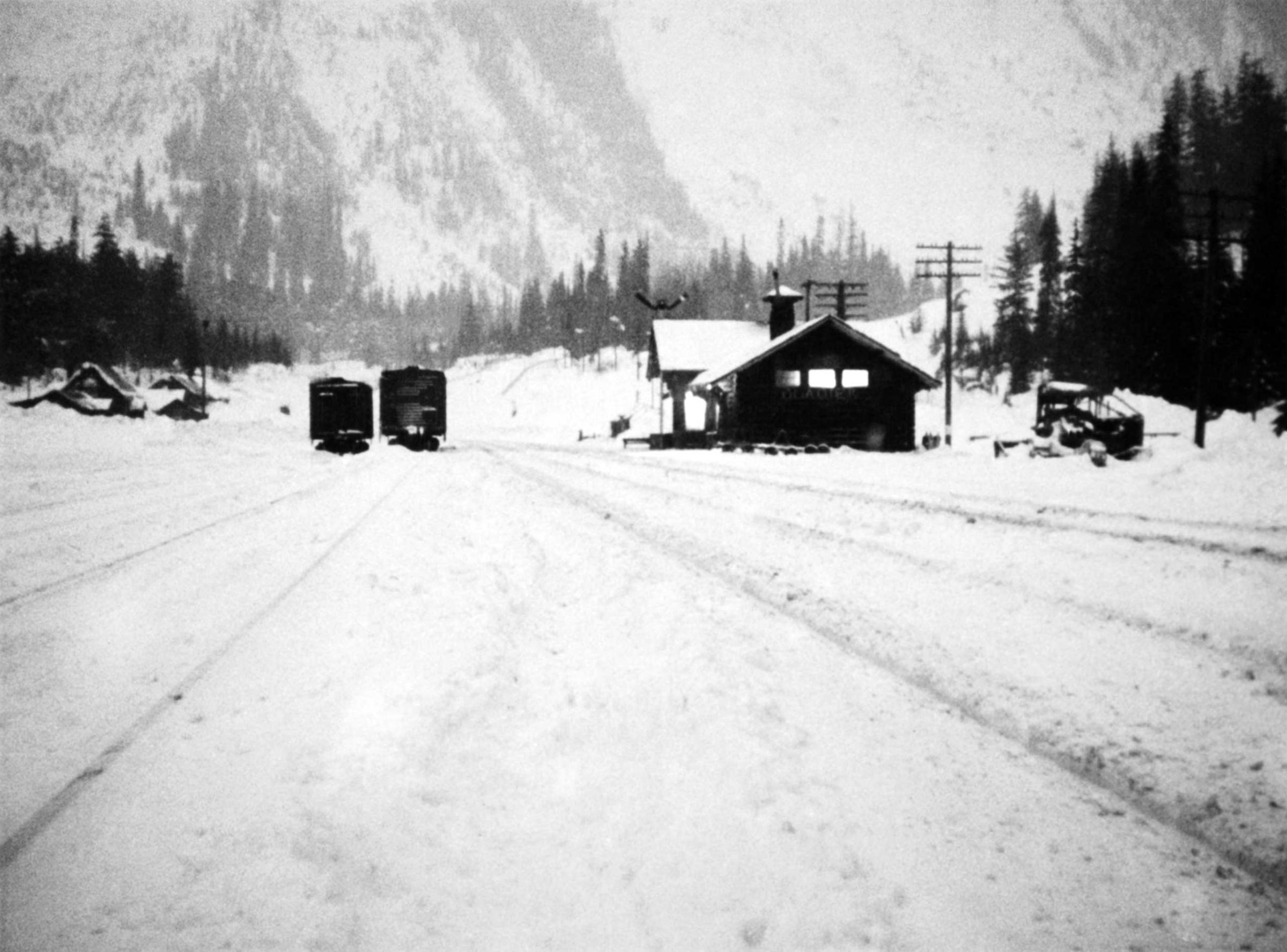

Nevertheless, as these photos show, there was plenty to gaze at. Since then Parks Canada has expanded significantly: it now oversees 46 national parks, plus more than 150 national historic sites.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com