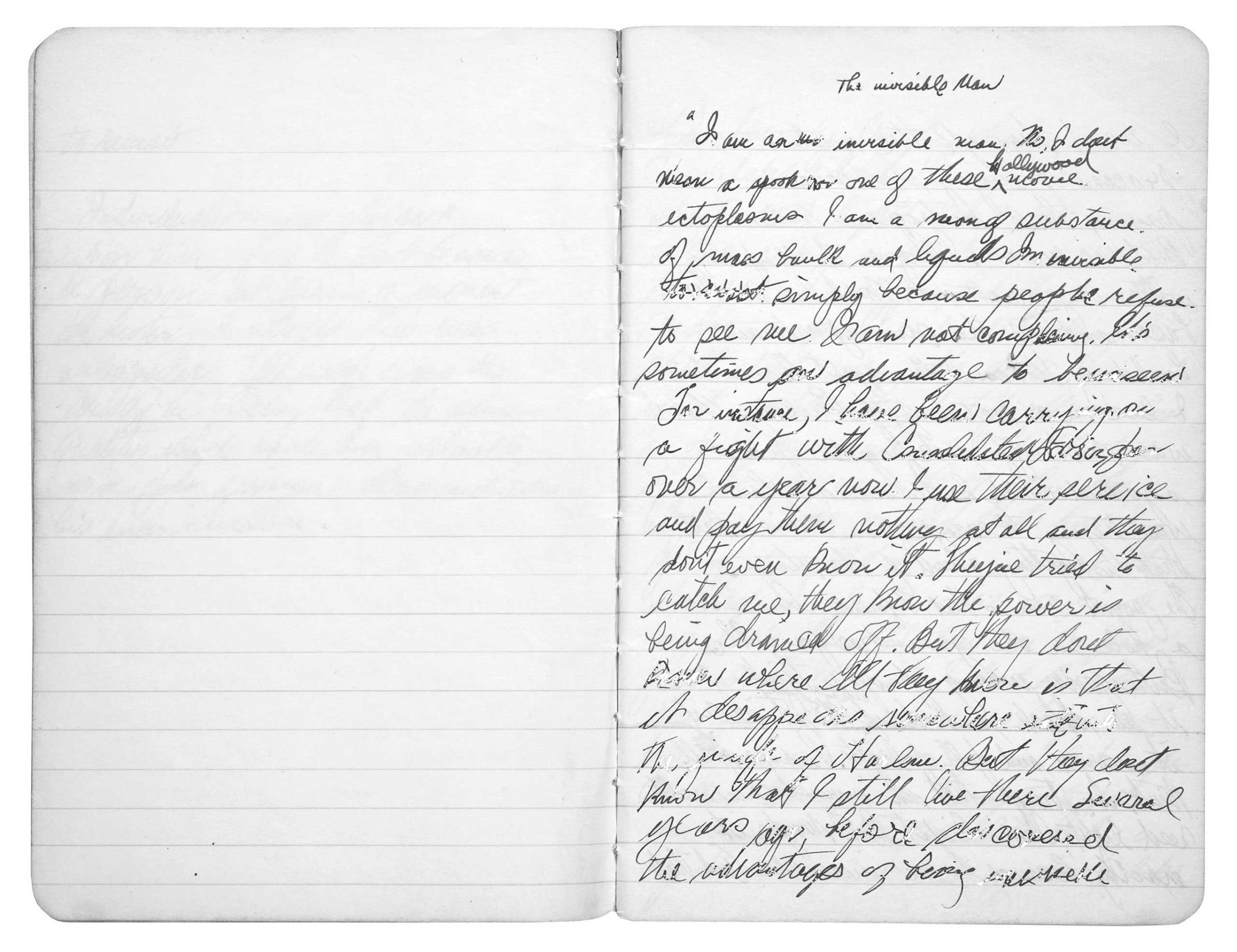

Gordon Parks, the renowned LIFE magazine photographer, and Ralph Ellison, the acclaimed novelist, shared a vision of Harlem — and that vision was grim. During the decade after the end of World War II, they collaborated twice on projects that were intended to reveal underlying truths about the New York City neighborhood that was sometimes called the capital city of black America. Their first effort, in 1947, was never published. In the second, “A Man Becomes Invisible,” which appeared in LIFE on Aug. 25, 1952, Parks interpreted Ellison’s recently published novel, Invisible Man, through images that were by turns surreal and nightmarish.

Parks and Ellison were friends as well as collaborators, and both were strangers to Harlem. Their roots, in Kansas and Oklahoma respectively, were culturally and geographically far removed from what Parks once called Harlem’s “shadowy ghetto.” While other African American artists celebrated Harlemites’ cultural achievements, Parks and Ellison both mourned the psychological damage that racism had inflicted on them. There was no room in their Harlem for a Duke Ellington or a Langston Hughes, or even for the ordinary pleasures of love and laughter. Instead Harlem was, in Ellison’s words, “the scene and symbol of the Negro’s perpetual alienation in the land of his birth.”

It is likely that the idea for the visual homage to Invisible Man came from Parks. The book was, after all, the work of a close friend—and had been partly written while Ellison was housesitting for the Parks family in 1950. LIFE’s editors would have been receptive to the idea. Invisible Man had been published to nearly universal critical acclaim and was one of the most talked about books of the year.

“A Man Becomes Invisible” was not LIFE’s first visualization of a book by an African American writer. For “Black Boy: A Negro Writes a Bitter Autobiography,” published in 1945, photographer George Karger recreated scenes from Richard Wright’s highly praised memoir. The images were dramatic but straightforward, illustrating the book rather than interpreting it. Parks, on the other hand, produced a self-consciously subjective interpretation.

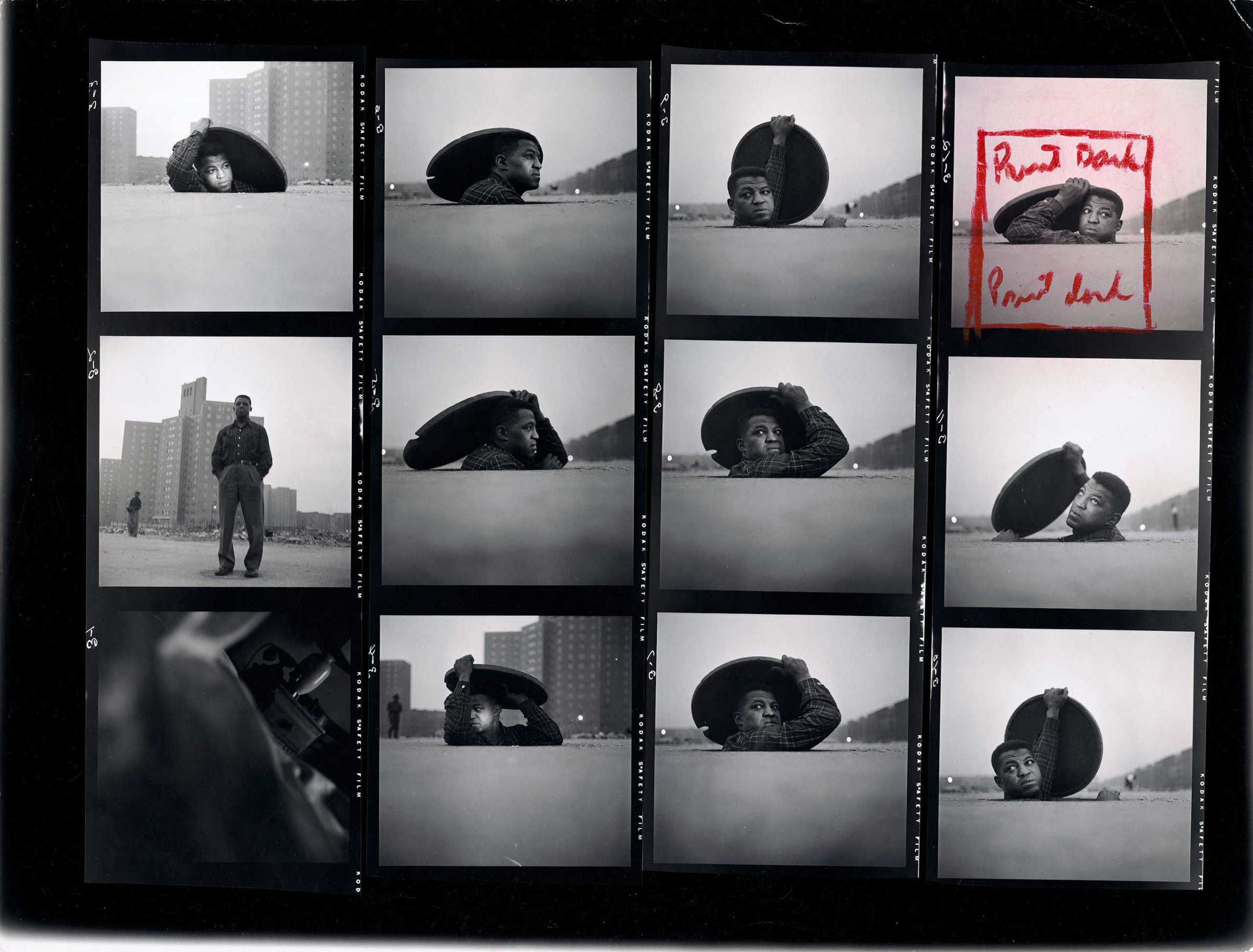

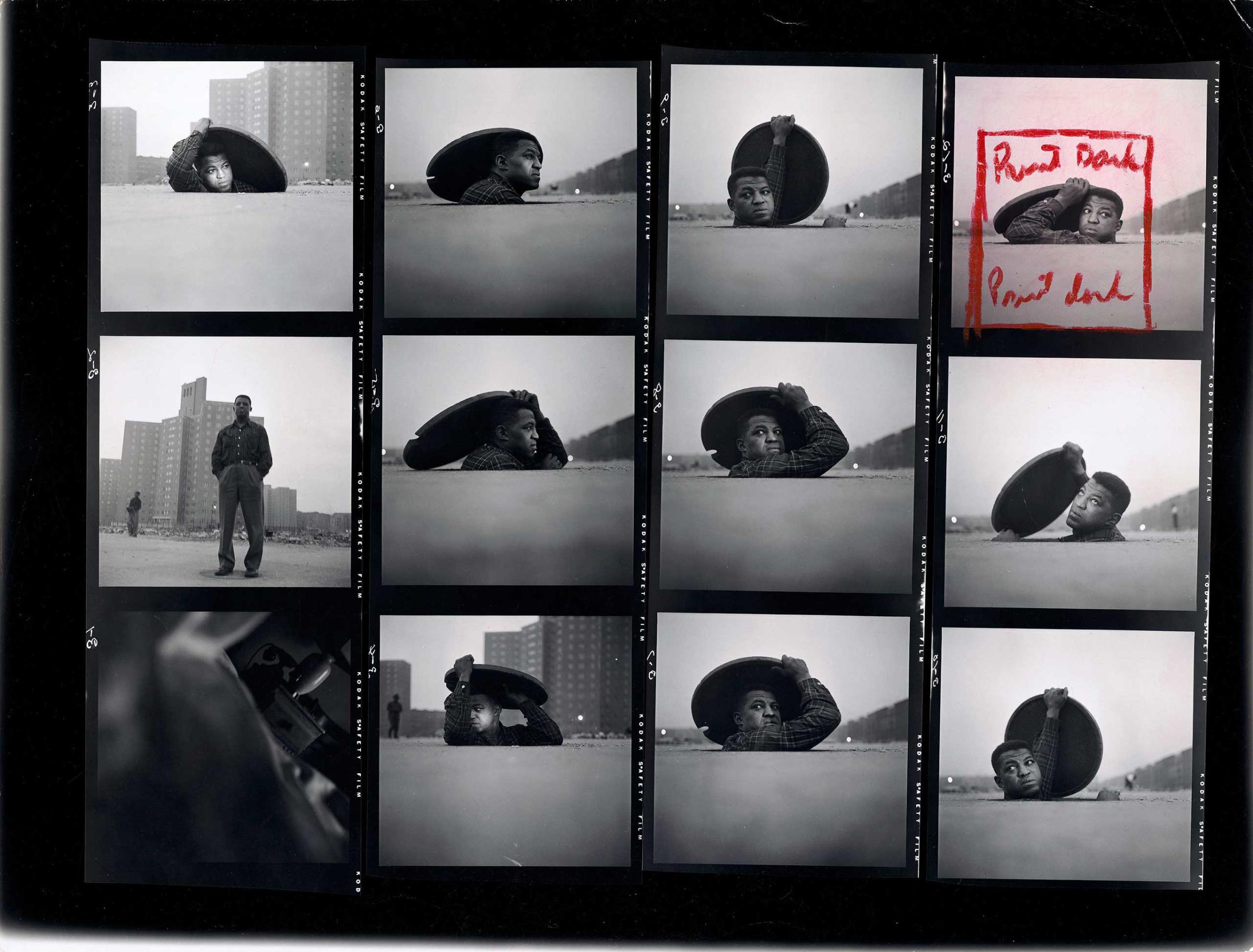

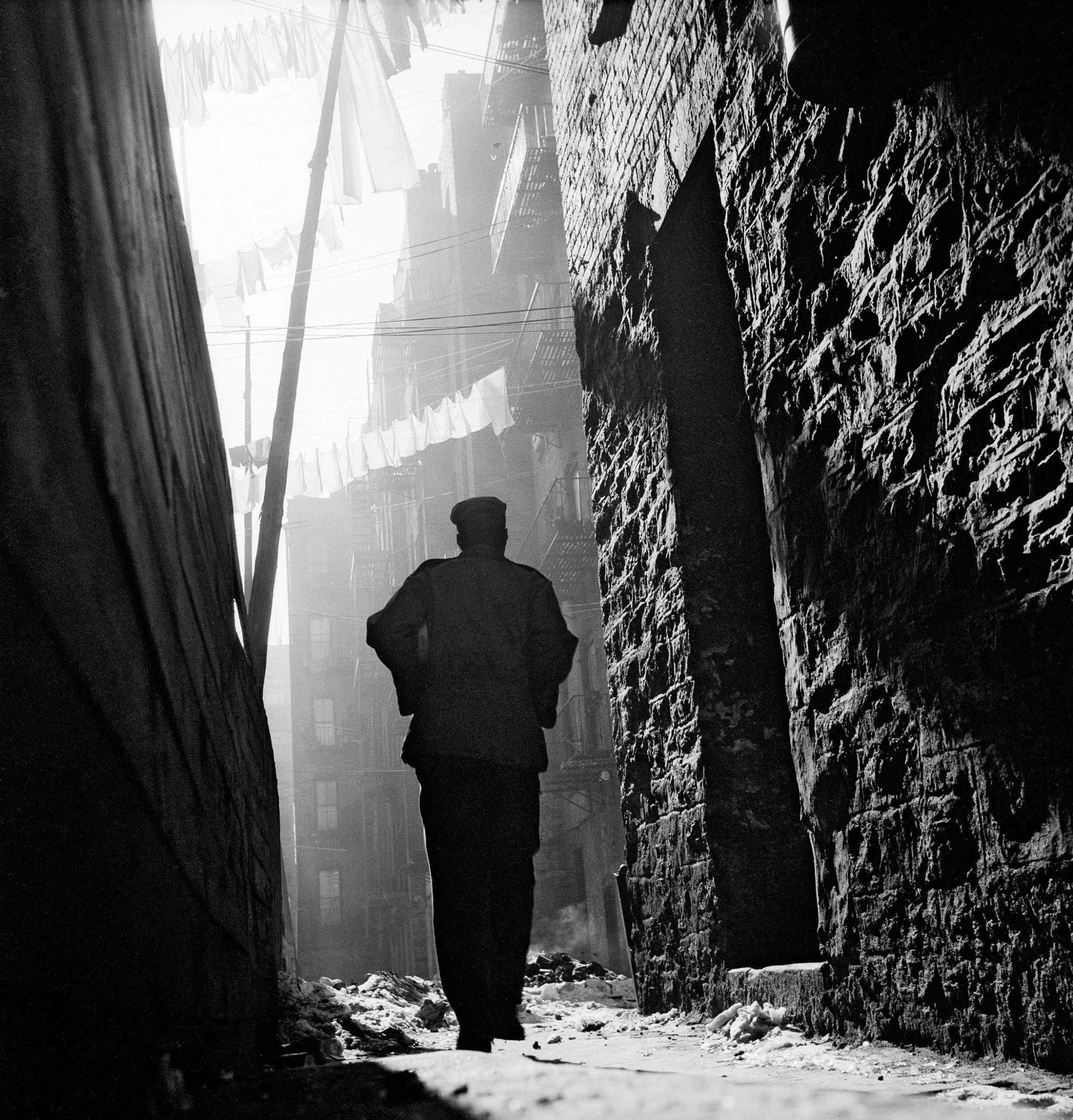

Both of Parks’ collaborations with Ellison are the subject of Invisible Man: Gordon Parks and Ralph Ellison in Harlem, an exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, which opens on Saturday and runs through Aug. 28. Writing in the exhibition’s catalog, curator Michal Raz-Russo notes that Parks made dozens of photographs for “A Man Becomes Invisible.” Many were gritty Harlem street scenes that Parks shot in a documentary mode. In others, he staged scenes in order to capture the surreal elements of Ellison’s novel. Raz-Russo argues that the photographic record suggests that Parks envisioned a more comprehensive interpretation than was possible in the three pages that his editors gave him. (Parks’ memoirs are silent on the matter.)

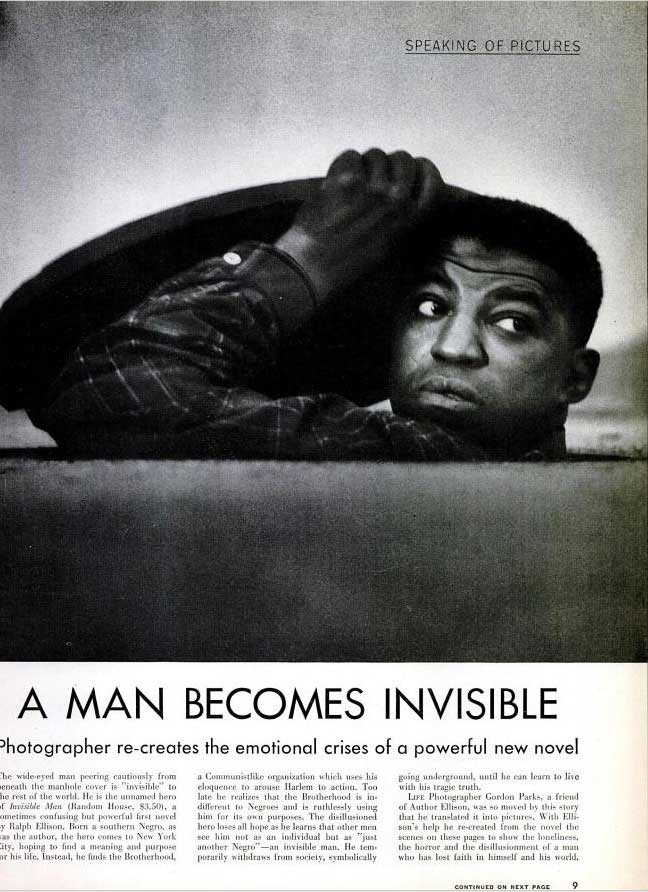

LIFE’s editors chose to publish only four of Parks’ photographs, all of them more surreal than documentary. The magazine’s most alert readers would have noticed that the first photograph in “A Man Becomes Invisible” did not depict a scene that appeared in Invisible Man. Instead it extended Ellison’s narrative, as Matthew S. Witkovsky, head of the photo department at the AIC, notes in his catalog essay. Occupying most of the page, it showed the novel’s unnamed narrator emerging through a manhole on a Harlem street. Below him was the sanctuary that had been his escape from the absurd and brutal forces of racism that had nearly destroyed him. Ellison had ended his story with his narrator preparing to reenter the world, but not having done so. Parks visualized the narrator’s reentry, capturing the wariness that he would have felt.

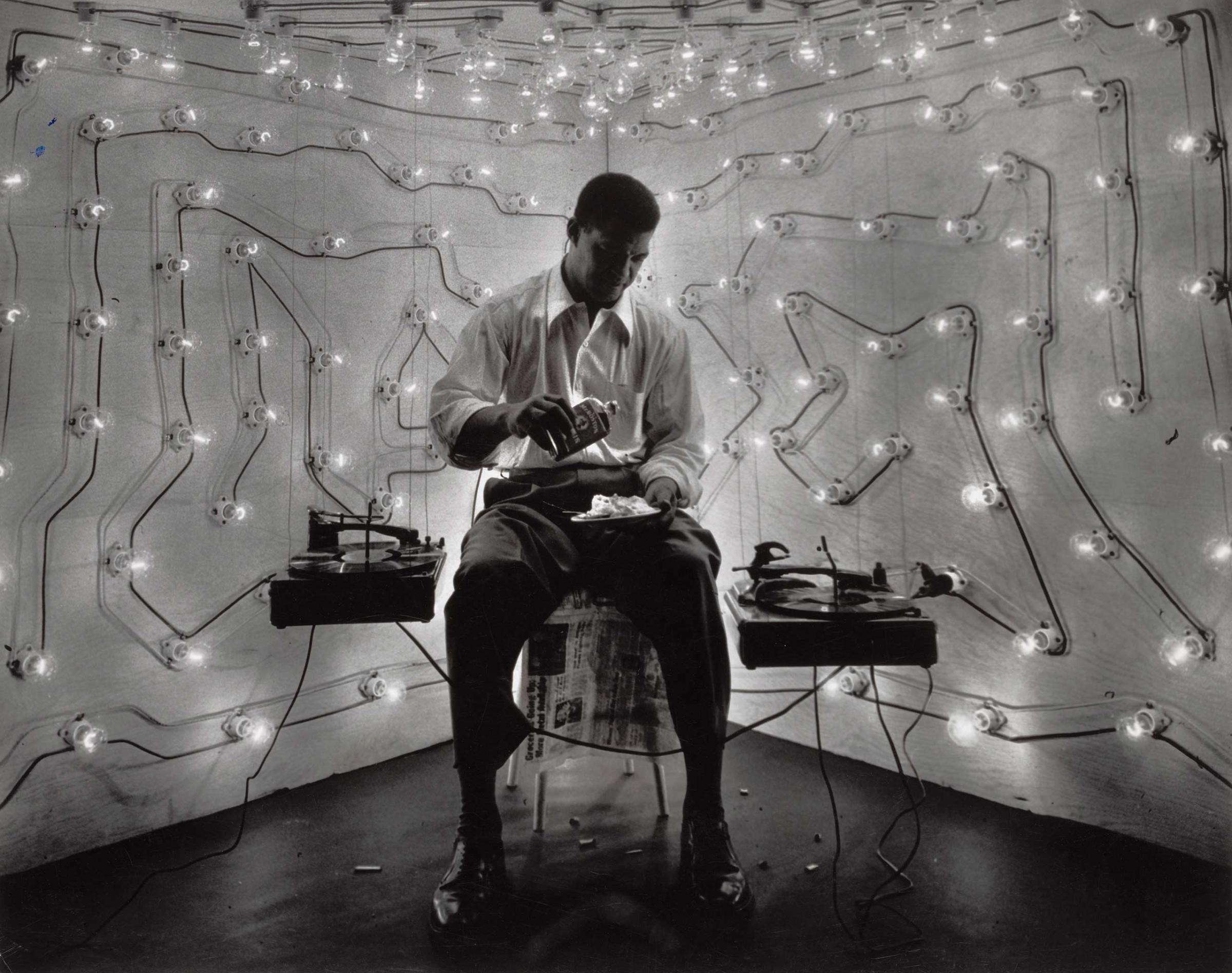

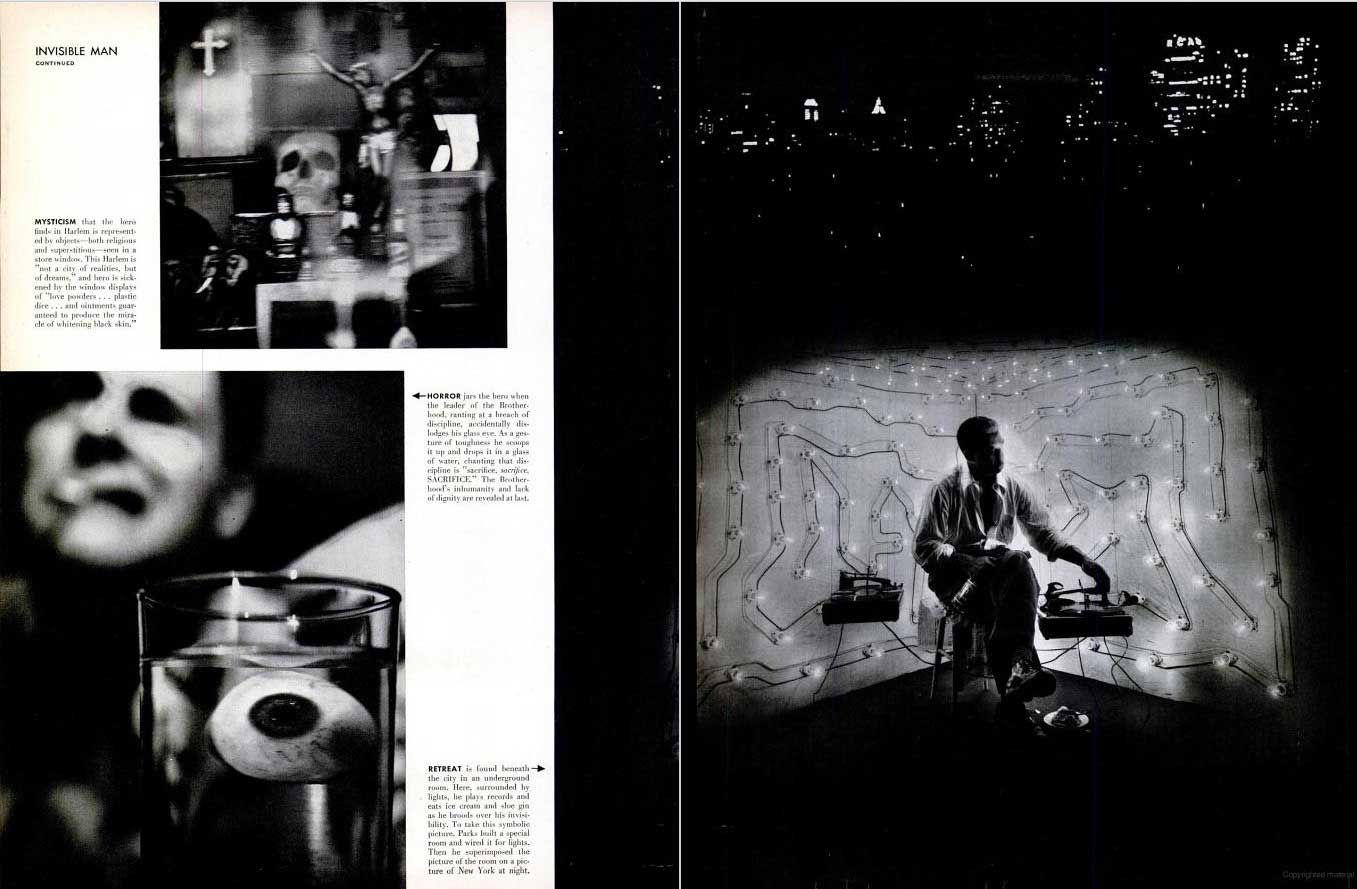

In the final photograph, Parks depicted the novel’s signature scene: the narrator in his underground lair, where he fought off his sense of invisibility in the glow of 1,369 lightbulbs, drinking sloe gin and listening to Louis Armstrong records. Above him burned the lights of New York’s nighttime skyline. A composite of two negatives, the image was a metaphor for the psychological damage that racism had inflicted on the narrator and, by extension, on all black Americans.

Two nightmarish photographs rounded out the photo-essay. In the first, Parks created a hallucinatory image out of what had been a straightforward documentary photograph of Harlem shop window filled with religious symbols and a skull. Farther down the page, he evoked a moment in which the leader of a stand-in for the Communist Party that Ellison called “the Brotherhood” attempted to intimidate the narrator, who had come to believe that the group was exploiting him, by removing his glass eye and tossing it into a glass of water.

The uncredited text that accompanied Parks’ photographs flattened the novel’s plot considerably, emphasizing its anti-Communist elements and downplaying its critique of American racism. Yet LIFE was undoubtedly correct when it said that Parks captured “the loneliness, the horror and the disillusionment of a man who has lost faith in himself and his world.” As Raz-Russo writes in her catalog essay, “A Man Becomes Invisible” “remains an important tribute to and interpretation of Ellison’s seminal novel.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com