When President Obama visits Hiroshima later this month, the trip will be the first time a sitting President has ever visited the site of where the U.S. dropped an atomic weapon in 1945. The visit will highlight the President’s “continued commitment to pursuing the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” the White House said in a statement on Tuesday, and the administration has stressed that such a visit is not meant to imply an apology.

The trip will come a full 42 years after the first Presidential trip to Japan drew calls for a visit to Hiroshima as well. But, despite generally positive relations between the two nations in the last few decades, the idea never actually came to fruition—until now.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The State Department’s records of official presidential visits to Japan begin in 1974, with Gerald Ford. Every President since then has made at least two visits to the nation, but as TIME reported during Ford’s trip, there was a reason why Ford was the first: “Dwight Eisenhower planned to go in 1960 but canceled the trip at the last minute because of massive protests by Japanese leftists. There were demonstrations in advance of Ford’s trip too, including firebombings of the American and Soviet embassies by extremists.”

MORE: See What the Only Hiroshima Building to Outlast the Atomic Bomb Looks Like Today

In fact, Eisenhower’s trip had been more than “planned”—it was already underway when Japan told the President to avoid Japan during his ongoing Asia trip. It was seen as, TIME noted in a cover story about the decision, “a stinging slap to U.S. pride and prestige” by “the hand of organized Communism” that had made the demonstrations in Japan intense enough to warrant fears for Eisenhower’s safety.

But, though Ford did set into motion a precedent of presidential visits, his trip only took him to Tokyo and Kyoto. Not that Hiroshima wasn’t considered: a 2009 investigation by the Japanese newspaper The Asahi Shimbun and the Investigative Reporting Workshop at American University found evidence in Ford’s presidential papers that he had been encouraged to make the trip Obama will now make. (The U.S. also dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki at the end of World War II.)

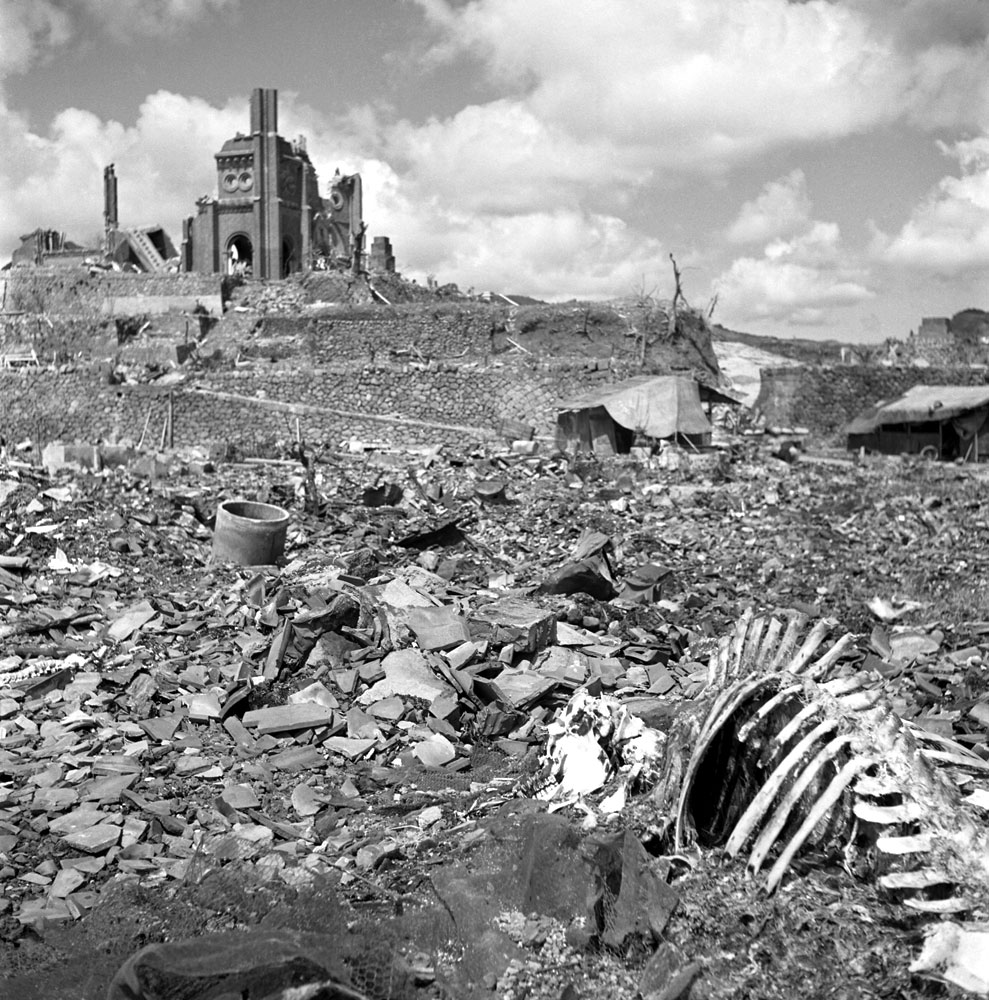

Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Photos From the Ruins

About two months before Ford’s trip, the investigation found, White House official William J. Baroody Jr. sent the President a memo urging him to go to Hiroshima to “provide indisputable assurance of your intent to heal wounds, both national and international.” At a time when Cold War nuclear proliferation was of concern, the visit would be both meaningful and useful, Baroody posited—in particular because Ford hoped “to receive assurances that the Japanese Diet would ratify the nuclear nonproliferation treaty,” as TIME put it back then. Others at the White House, however, felt that such a visit would be adding a dose of negativity to an otherwise positive trip, and that it would risk opening old wounds.

That view won out in the end, and Ford skipped Hiroshima.

MORE: See the Original Operations Orders for the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Similar concerns prevented later trips to Hiroshima. As recently as 2009, Japan discouraged Obama from including the city in a trip to Japan, because “the public’s expectations” for such a visit would be too complicated to manage.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com