In the documentation of U.S. history through photography, a fundamental component has long been overlooked by the art and media world: black photography by black photographers. For a long time, magazines, museums, galleries and art institutions have been unable or unwilling to acknowledge it or grasp its essence.

With few outlets and publishers, and little support or public attention, black photographers have had to achieve some visibility for themselves and their art, bringing the spirit of blackness to the public through paths that were often more complicated.

“Blackness in photography has been overlooked, but that has not deterred us,” says Jamel Shabazz, a legendary street photographer who has made an incomparable contribution to black culture. “Actually it has propelled many to take a proactive position and do for self, despite the many obstacles and roadblocks.”

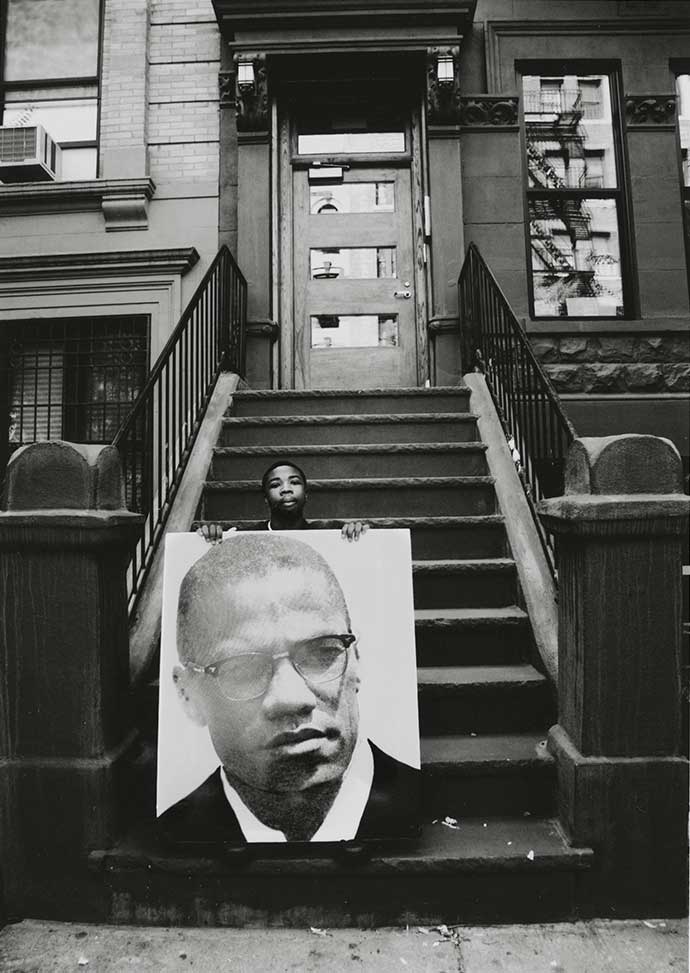

That “proactive position” was the monograph “The Sweet Flypaper of Life”, the first to be published by a black photographer, Roy DeCarava, in 1955, three years after Aperture magazine was founded. The second monograph by a black photographer, “House of Bondage” by Ernest Cole, came more than a decade later. It was Kamoinge, a NY-based collective of African American photographers – of which Shabazz is a member – established in 1963, six years before the Metropolitan Museum of Art presented James Van Der Zee’s “Harlem on My Mind”, that put together the first retrospective on a black photographer’s work, bringing scenes of life on 125th street to a prestigious and international stage.

More than five decades later, Aperture is publishing an issue dedicated to blackness and black culture in photography – a first for the publication – with conversations between photographers, authors, artists, historians and experts under the masterly direction of distinguished guest editor Sarah Lewis, a professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard University.

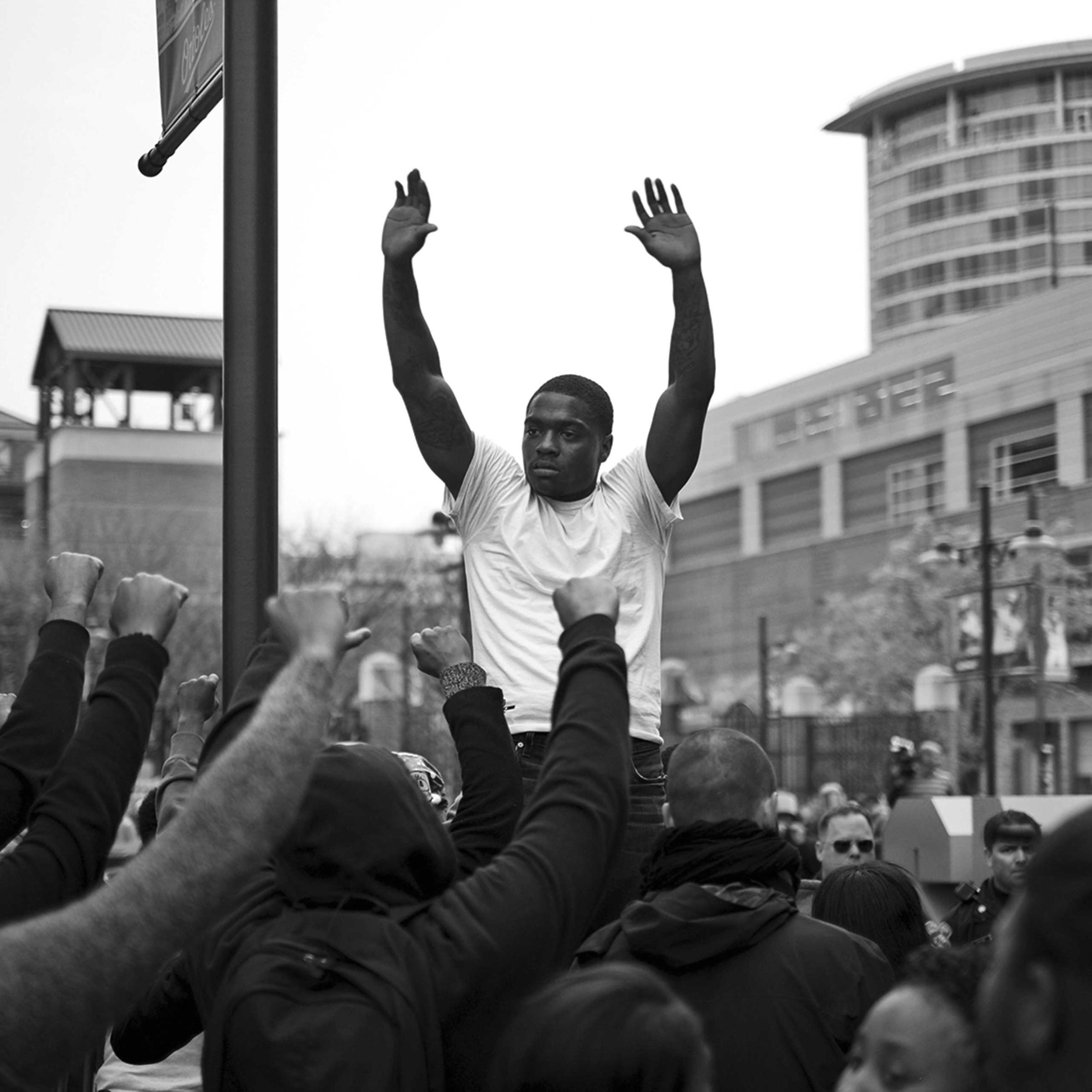

The issue, called “Vision & Justice,” comes at a time astir with thoughtful considerations about black culture and a new quest for self and identity: The Obama administration coming to a close, concerns over rampant social injustice and civil rights, and debates about equal opportunity and discrimination (with #BlackLivesMatter and #OscarsSoWhite trending in the public opinion), not to mention Beyoncé’s latest album bringing black womanhood to mainstream attention.

Inspired by Frederick Douglass’ 1864 speech in “Picture and Progress”, the diptych of vision and justice entails “not just the power of art but the power of how [art] shifts perception,” and what happens “in us as a result,” Lewis says.

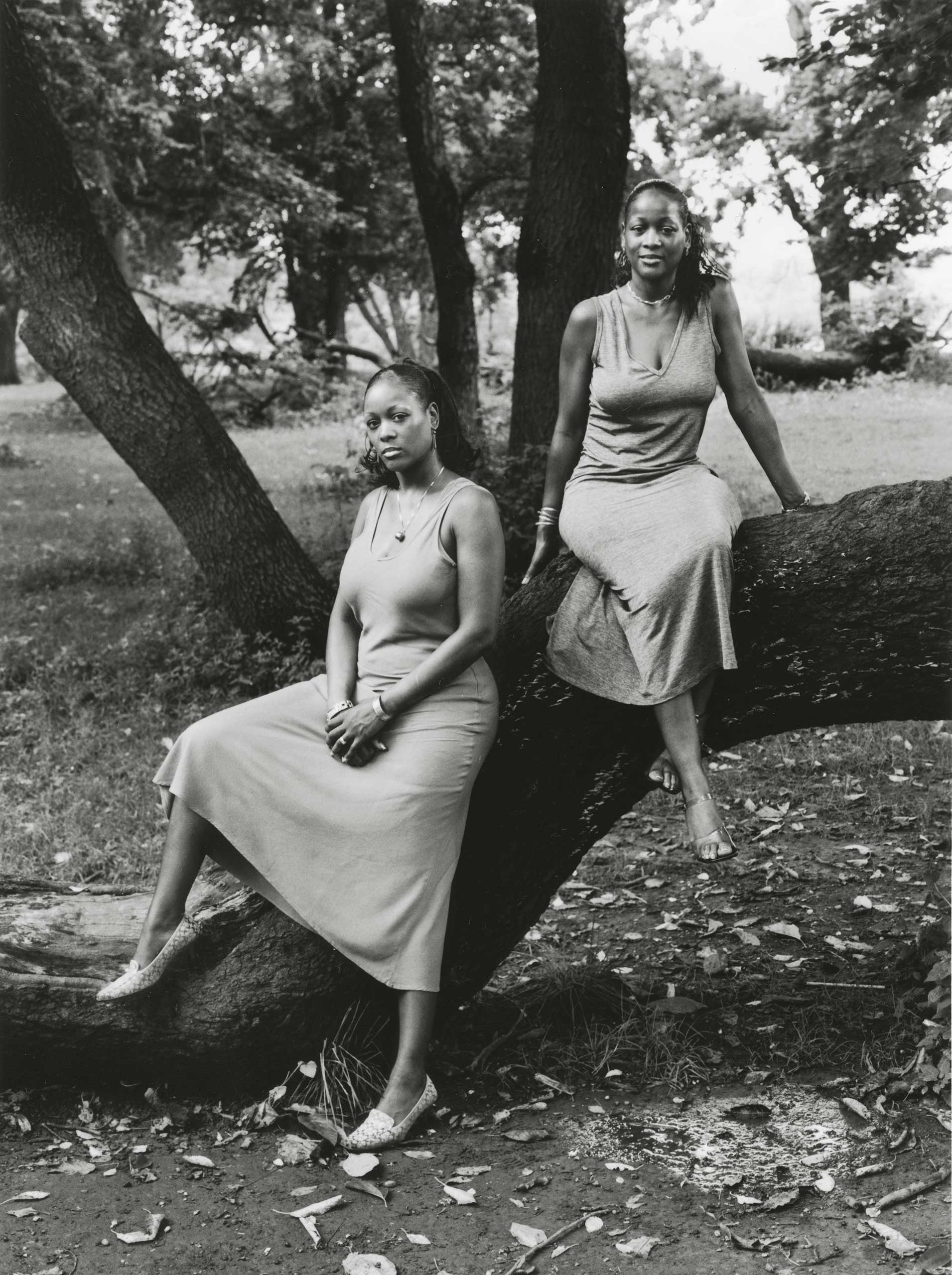

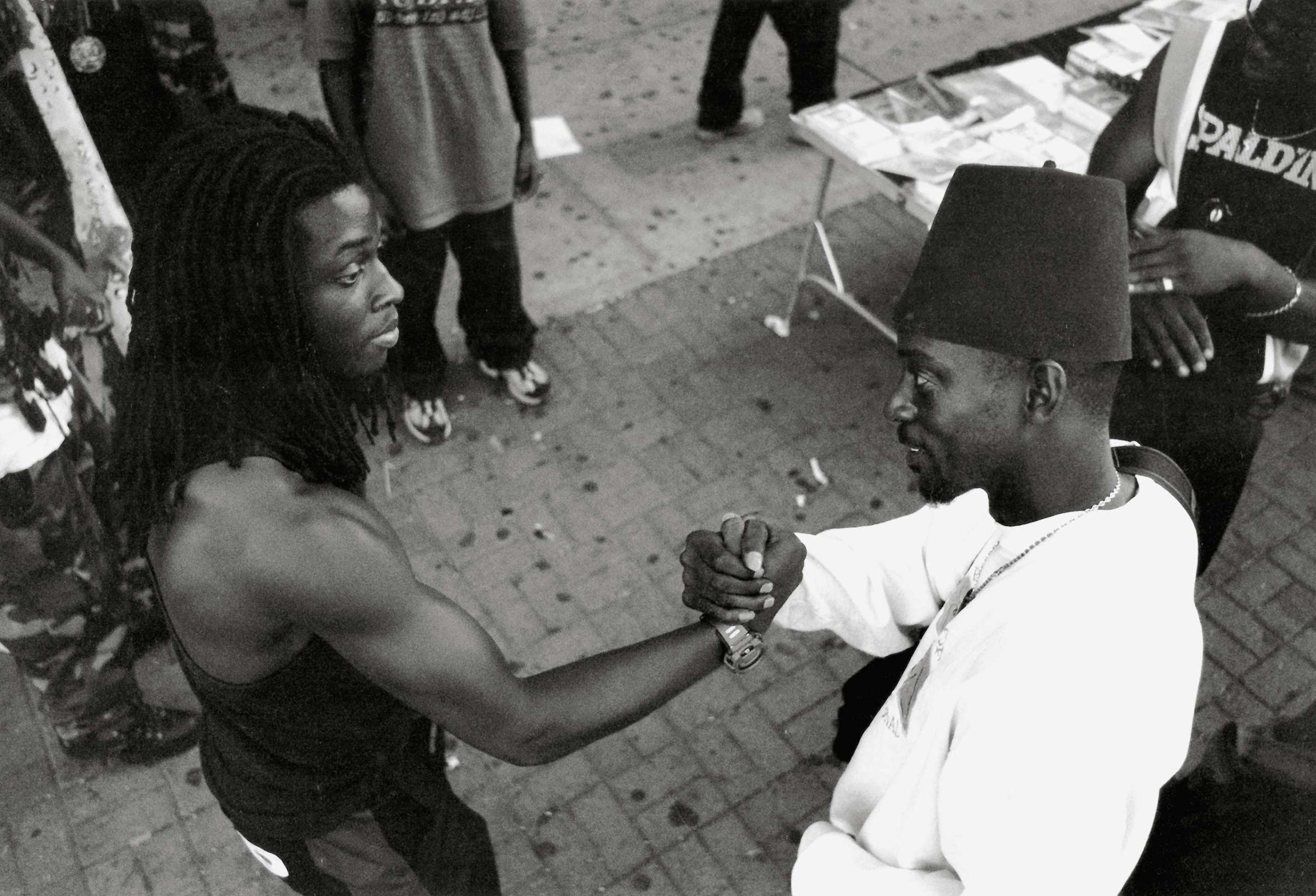

To give full representation of blackness and Afro-American culture, the issue brings together the work of a broad range of photographers who, in different times and places, have chronicled the resilience, beauty, and values of black people. It’s an extensive exercise in “retrospective” and correction where the breadth of the works restores a plurality of topics necessary for full representation of the black experience.

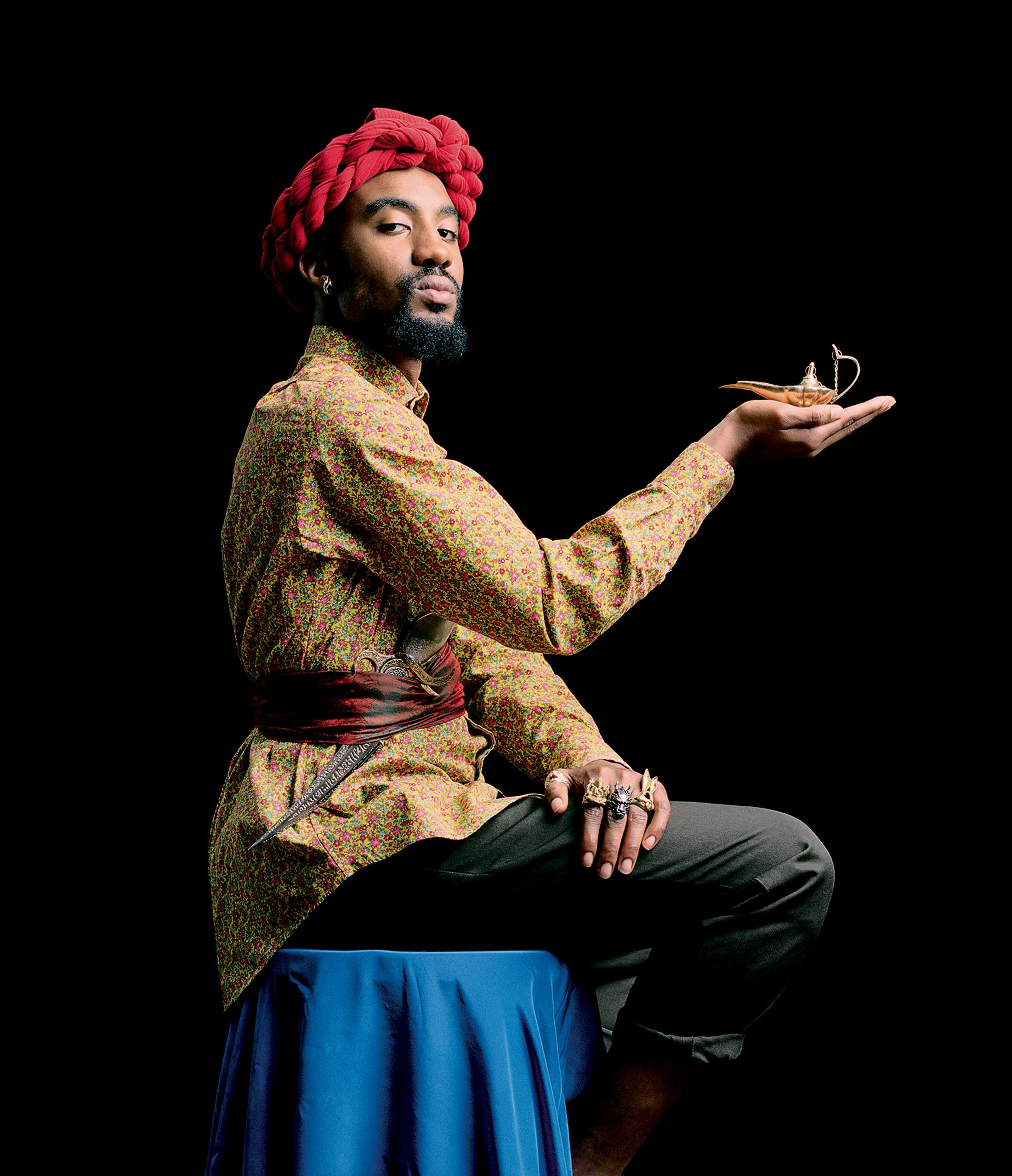

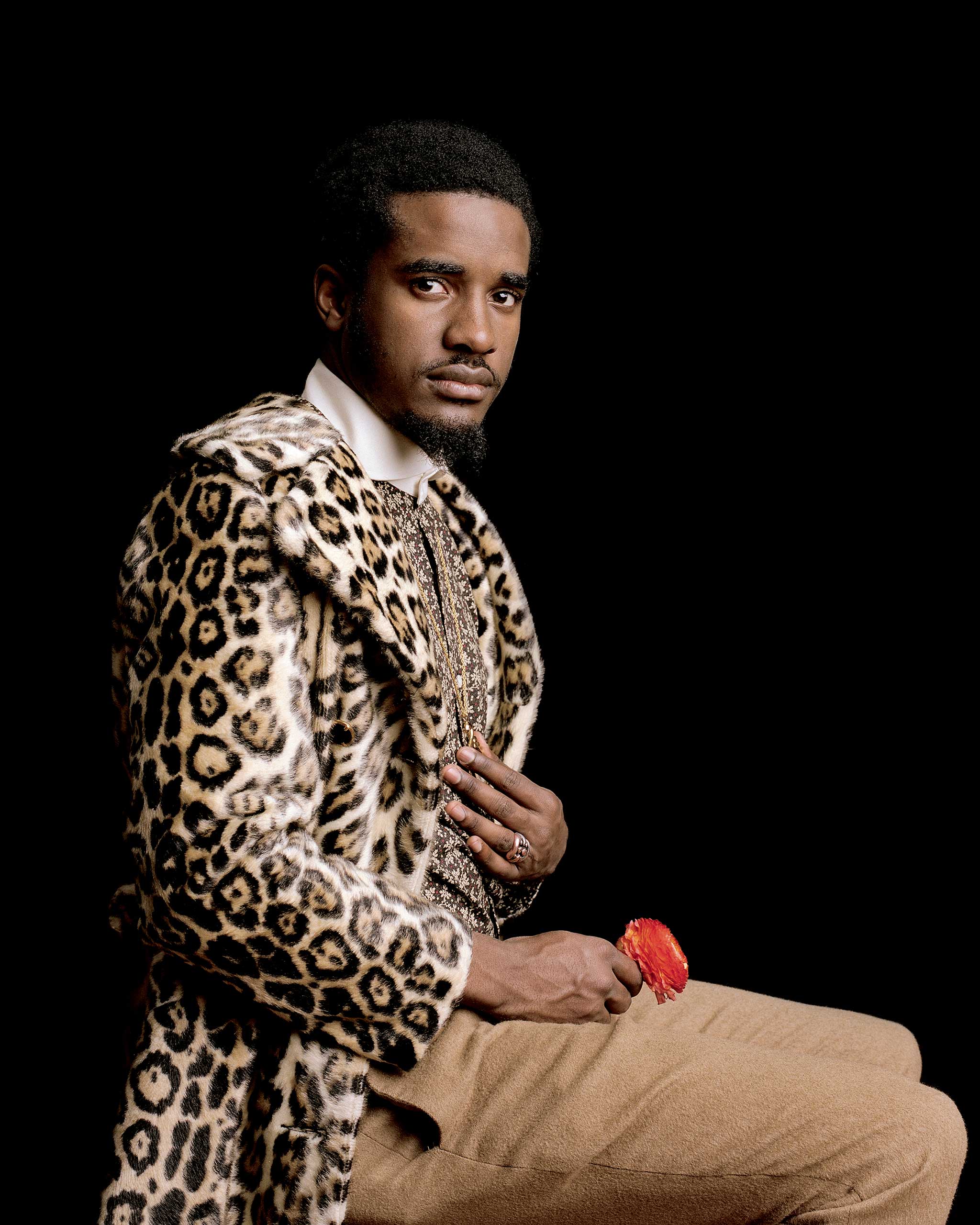

Douglass called for images to “show the variation in forms of black subjectivity,” historian and intellectual Henry Louis Gates explained in this issue, in order “to display individual black specificity,” an aspect mostly dismissed by mainstream representation which has promoted instead a stereotypical black imagery of violence and illiteracy. Discussing visual representation, Douglass attempted both to “display and displace,” longing for a disruptive and creative action not too dissimilar from what American-Ethiopian artist and photographer Awol Erizku achieves in his work.

By alluding to the Dutch painting “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” and transfiguring that girl into a young black woman with a heart-shaped bamboo earring, Erizku aims to confer upon her black aesthetic the same universality that the white aesthetic has held for a long time, addressing that gap in representation and self-expression. His groundbreaking work – not only “Girl with a Bamboo Earring”, but also “Reclining Venus” inspired by Manet’s Olympia – bring attention to the black body, which is “still a very powerful device in the art world,” according to Erizku, who aims to make it something as “universal and ubiquitous” as the white female body in art. “All these things have a cultural significance,” Erizku explains, and the minimal approach in his photographs hides their layered complexity, which brings us back to Douglass’ aim to “display and displace.”

A black model boasting an Afro-punk hairstyle shot by Erizku graces the cover of this issue of Aperture, along with Richard Avedon’s shot of three generations of Martin Luther Kings dated 1963 – a very contemporary and historical approach for a double cover that signals “the polysynaptic breadth of works [and] honors the complexity of the work in the issue,” Michael Famighetti, editor of Aperture magazine, explains.

The issue is composed of many accomplished photographers including Shabazz, Erizku, Deborah Willis, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Deana Lawson, Lyle Ashton Harris, Ruddy Roye and Devin Allen, to name a few. It also features prose by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Carla Williams, along with essays and columns about cinematic representations, Obama’s legacy and jazz musicians, among others.

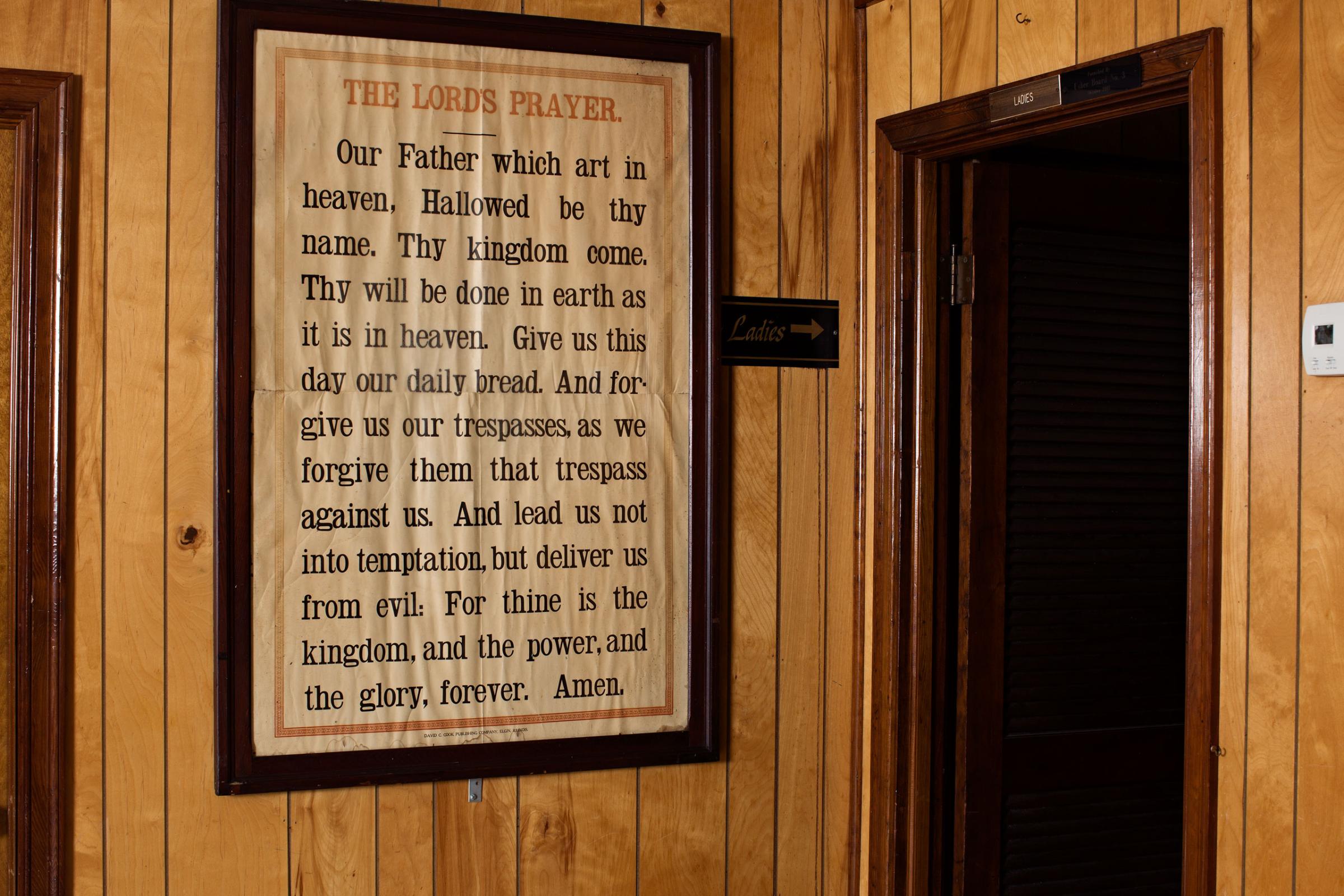

Telling Charleston's Story in Photographs

Altogether, these contributions manifest that groundbreaking idea of visual plurality that Douglass envisioned as leading to a more comprehensive representation, a conscious vision that will serve as the foundation of representational justice. “A broader representation of black life” is the plurality that renowned author, photographer, and historian Deborah Willis sees photographers pursuing.

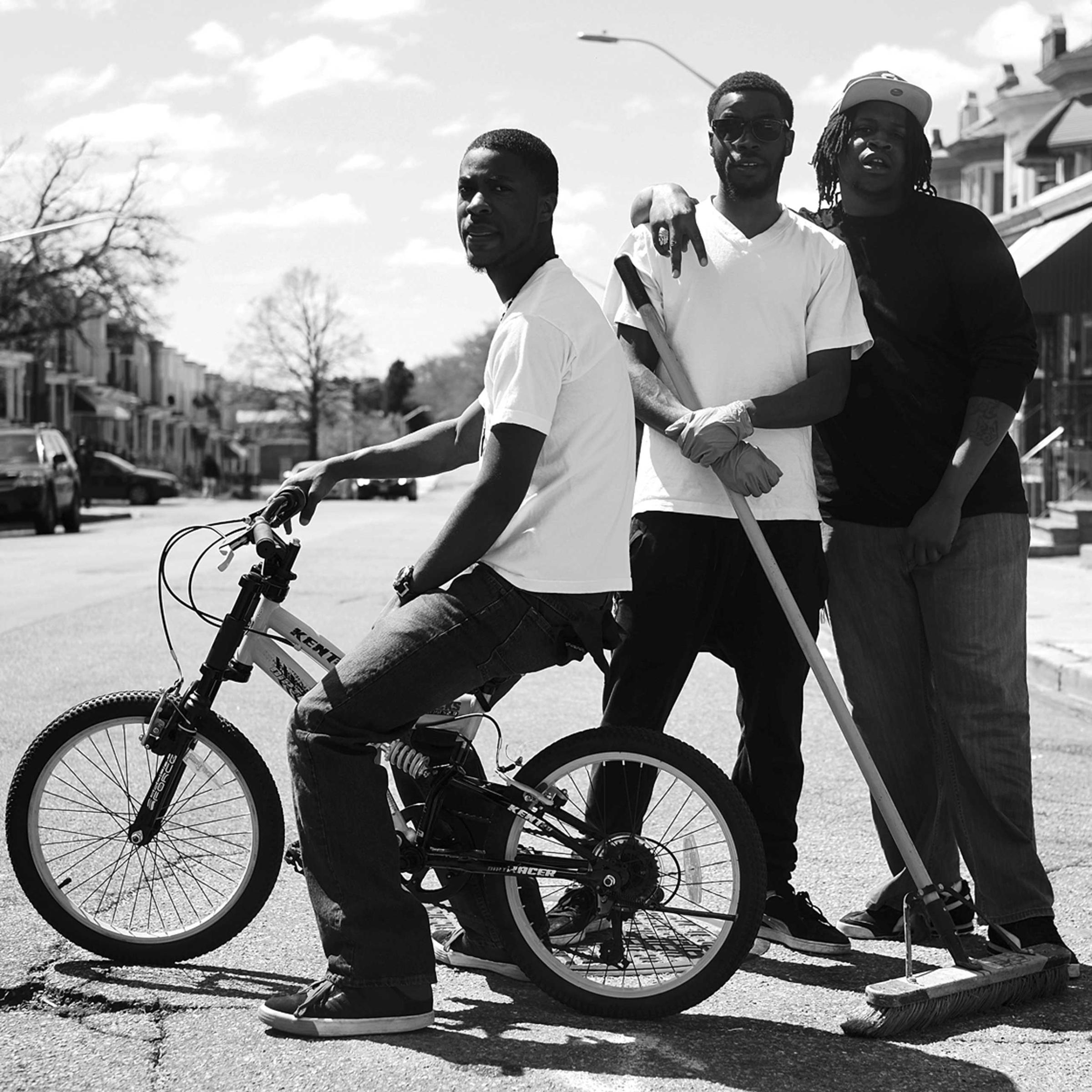

One of the great difficulties is learning how to disrupt a single narrative and understanding that there are multiple narratives in black life, Willis adds, praising the renewed sense of self-empowerment that drives photographers to follow their passion. “[T]hey are focusing on the joy that is in their communities. They are focusing on the injustices that are part of their communities,” but they are also discovering new selves, she adds. “Photographers are doing a lot of self-portraits and […] also looking in the mirror and performing different identities that they like to see about themselves,” Willis says.

Go Behind TIME's Baltimore Protest Cover With Aspiring Photographer Devin Allen

However, a gap still persists when it comes to the representation of and by black figures in the art world, Erizku notices. “There is a landslide in comparison,” the artist says about white representation and featured artists. Shabazz echoes Erizku’s feelings, referring to the original message he tried to convey in the 1980s: “that we are a beautiful and culturally rich people who have endured extreme hardships, yet we still persevered.” Shabazz adds, “I was also trying to make people aware that our communities were at risk of being dismantled and our men were being demonized and targeted. Sadly, the message has not changed nor the conditions.”

However, the fabric of black culture – its strength and grace – remains strong. “The seeds of that great endeavor continue to flourish today,” Shabazz says, “inspiring a new generation of photographers whose work reflects honor and dignity.”

Aperture will release “Vision & Justice” on May 24. An exhibition will be on view at the Harvard Art Museums from August 27, 2016 to January 8, 2017.

Lucia de Stefani is a freelance writer and frequent contributor of TIME LightBox.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com