On the night that Donald Trump effectively won the Republican nomination for President, Hillary Clinton observed radio silence. She had lost Indiana to Bernie Sanders, a small embarrassment in a year of galling humiliations. Indiana was a stubborn reminder of her weaknesses after a series of powerful victories in the Northeast–the sort of victories that Bill Clinton never won in 1992 until the general election. By contrast, his New York primary victory in ’92 over Jerry Brown was Pyrrhic, even though it pretty much clinched the nomination for him; he was battered by the tabloids, he seemed exhausted, his unfavorables were stratospheric.

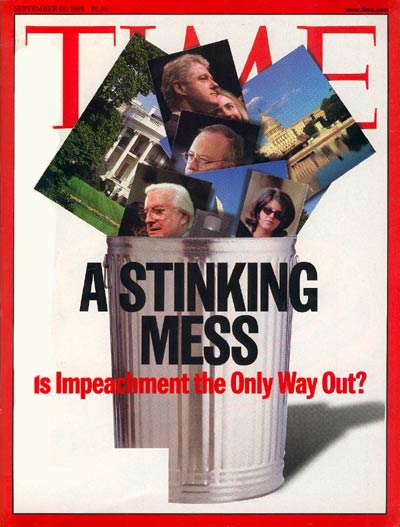

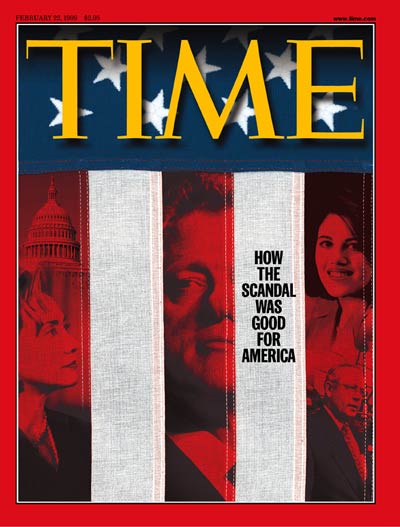

He had larger problems than an email server: he had recently been found out as a Vietnam draft dodger and a womanizer. People called him Slick Willie. Within weeks, he would be in a deeper, darker hole than Hillary has experienced this year–he would be running third, behind George H.W. Bush and the independent Ross Perot. By June, only 13% of the public thought him trustworthy. He was toast.

This is old news, but it’s living history for the Clintons. It is what keeps Hillary buoyant, even as the most glamorous Democratic constituencies–celebrities, idealistic college kids–have flocked to Bernie Sanders. More than any other politicians I’ve covered, the Clintons have a perfect sense of chronology. They know that politics moves more slowly than the daily media frenzy, that new story lines–comebacks, especially–are catnip to cable networks. They know that polls can change, that Trump will have his day, that the general election will be Armageddon. But they are confident she’ll win.

Bill Clinton had help in his 1992 comeback. Perot proved to be something of a loony: he dropped out of the race in July and then dropped back in for the debates that fall. Bush was uninspiring throughout. But Clinton also made his own luck. His choice of Al Gore as Vice President was unconventional: Gore seemed a Clinton clone, young and moderate and Southern, rather than the usual ticket balancer–and his campaign team’s sense of tactics was refreshing. When Clinton and Gore took off on a celebratory bus tour through America right after the Democratic convention, the election was all but over. (Clinton’s domination in the fall debates sealed the deal.)

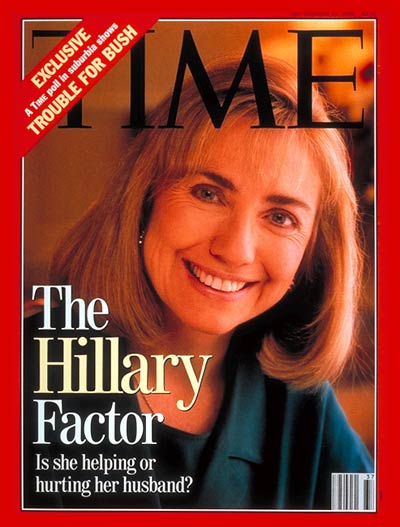

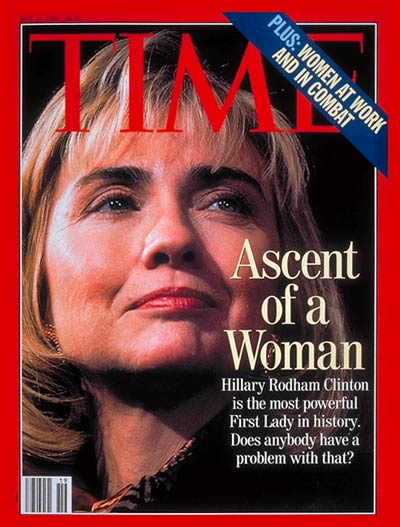

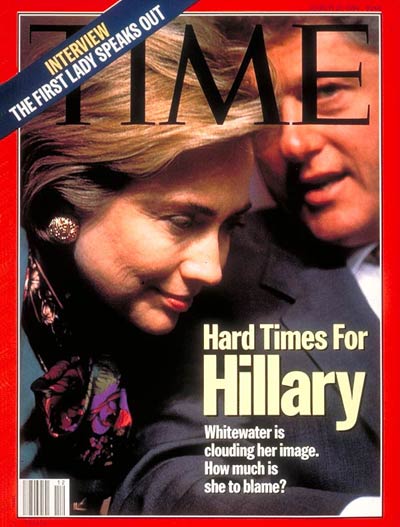

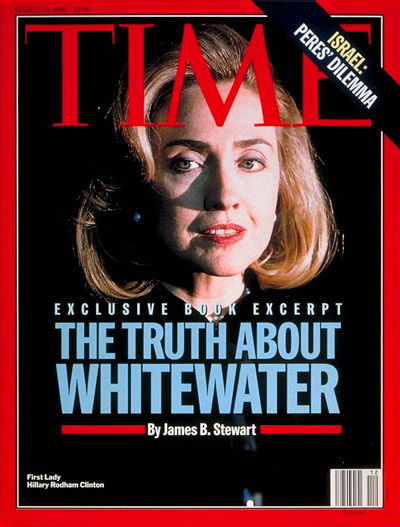

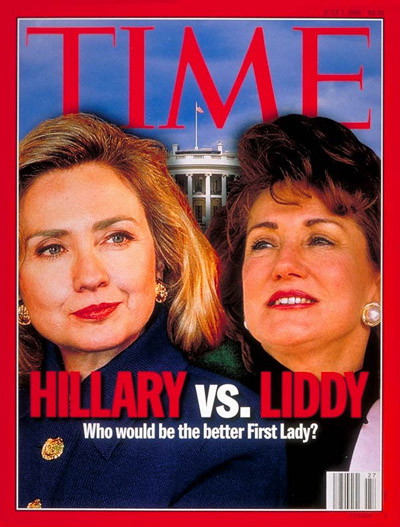

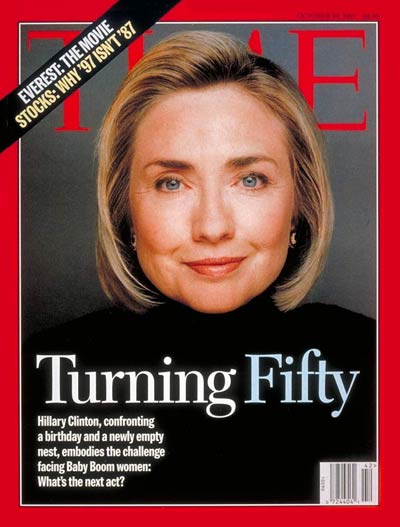

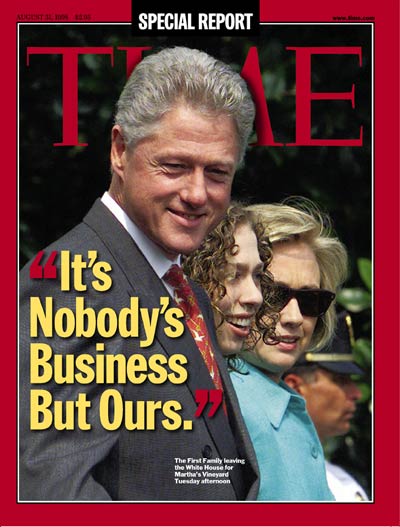

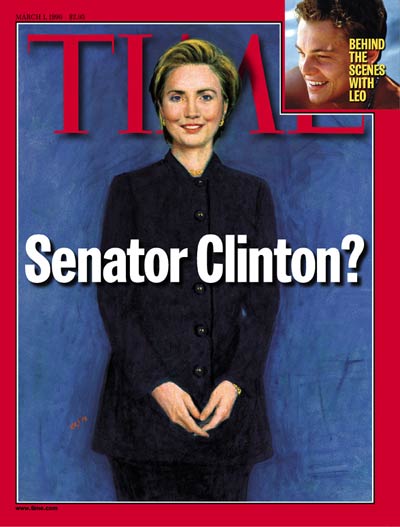

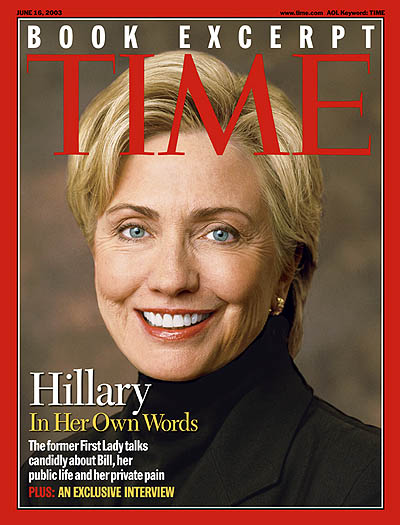

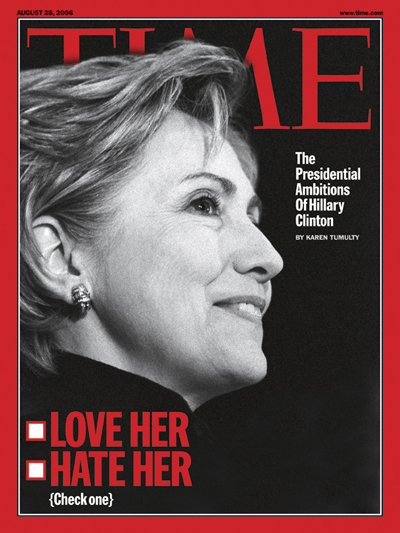

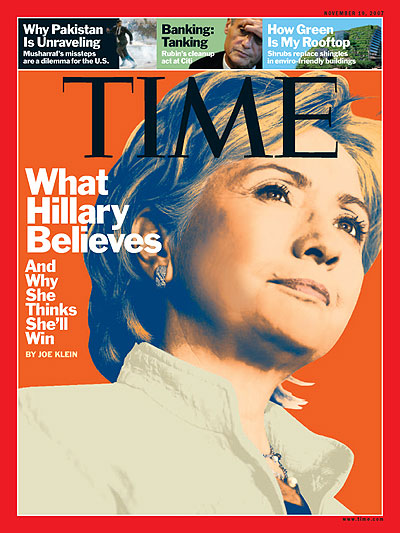

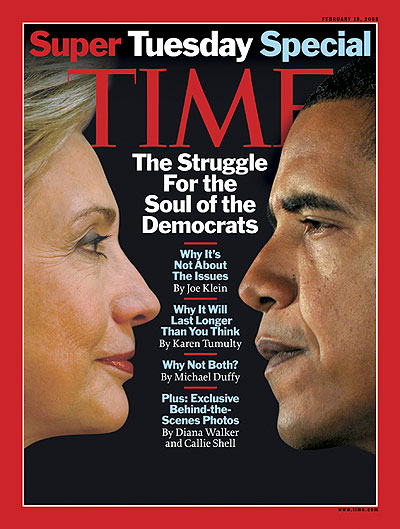

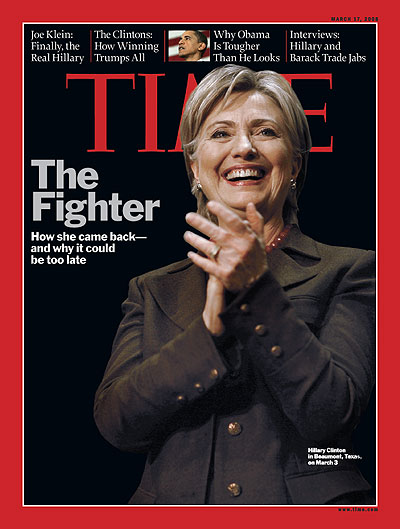

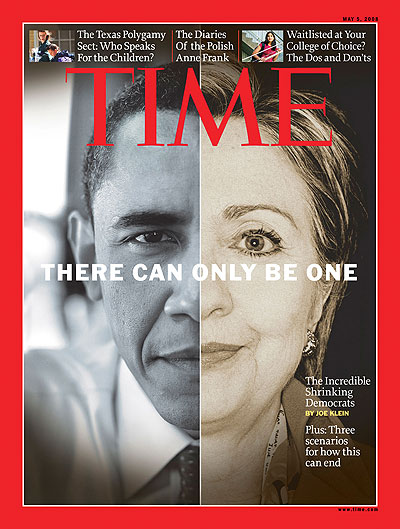

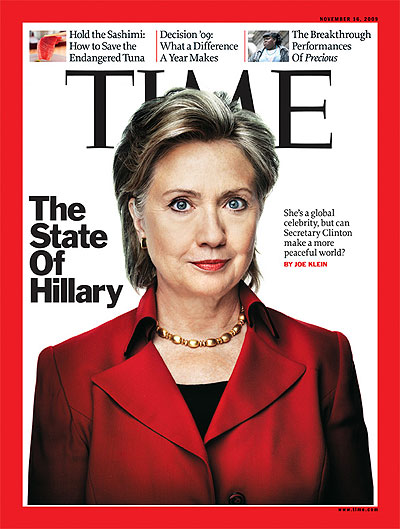

See Every Hillary Clinton TIME Cover

In some ways, Hillary faces an easier task. Donald Trump is an implausible President of the United States. But she has a problem that Bill never had. He swept to the presidency on a wave of pure energy and enthusiasm–this was something new, the baby boomers were taking over! Hillary is the George H.W. Bush of this campaign, selling stability–which may prove to be a marketable asset, given the craziness on the Republican side–but momentum feeds on excitement. Core polling perceptions like “trustworthiness” can turn, but they need some impetus.

Her vice-presidential choice will be important. A traditional pick would be someone young and Latino and male, but Hillary’s equivalent of an Al Gore would be … Elizabeth Warren. Another woman, but an outsider; a candidate who could rally Bernie’s legions of new voters, and who would be an excellent attack dog (a crucial vice-presidential function). I know, I know: the Clinton camp mistrusts Warren. She’d be a loose cannon, a risk. Her presence on the ticket might limit Hillary’s attempts to woo moderate Republicans and foreign policy hawks, which raises another possibility: Why not pick a moderate Republican woman–Condoleezza Rice, South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley–to stem the barbarian tide? That would be unthinkably new.

Inevitably, the vice-presidential selection will take a backseat in the general election. The presidency is won in discrete moments, as the public gauges the humanity of the candidates. Donald Trump is more a brand than a person; given the spray tan and egregious comb-over, he looks more like a panjandrum in The Hunger Games than a regular guy. How many spontaneous, empathetic human interactions has he had with individual voters? None that I can remember. He is all facade.

There is a basic rule of politics in the television age: warm always beats cold (with the exception of Richard Nixon). Hillary Clinton’s ultimate trump card will be not her gender but her relative humanity–an ironic twist given her public awkwardness. Her decision to sit down with West Virginia coal miners and apologize for her harsh, but realistic, prediction that they’ll be losing their jobs is the sort of thing that would be unimaginable for Trump. In the amped intimacy of a presidential campaign, such moments matter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com