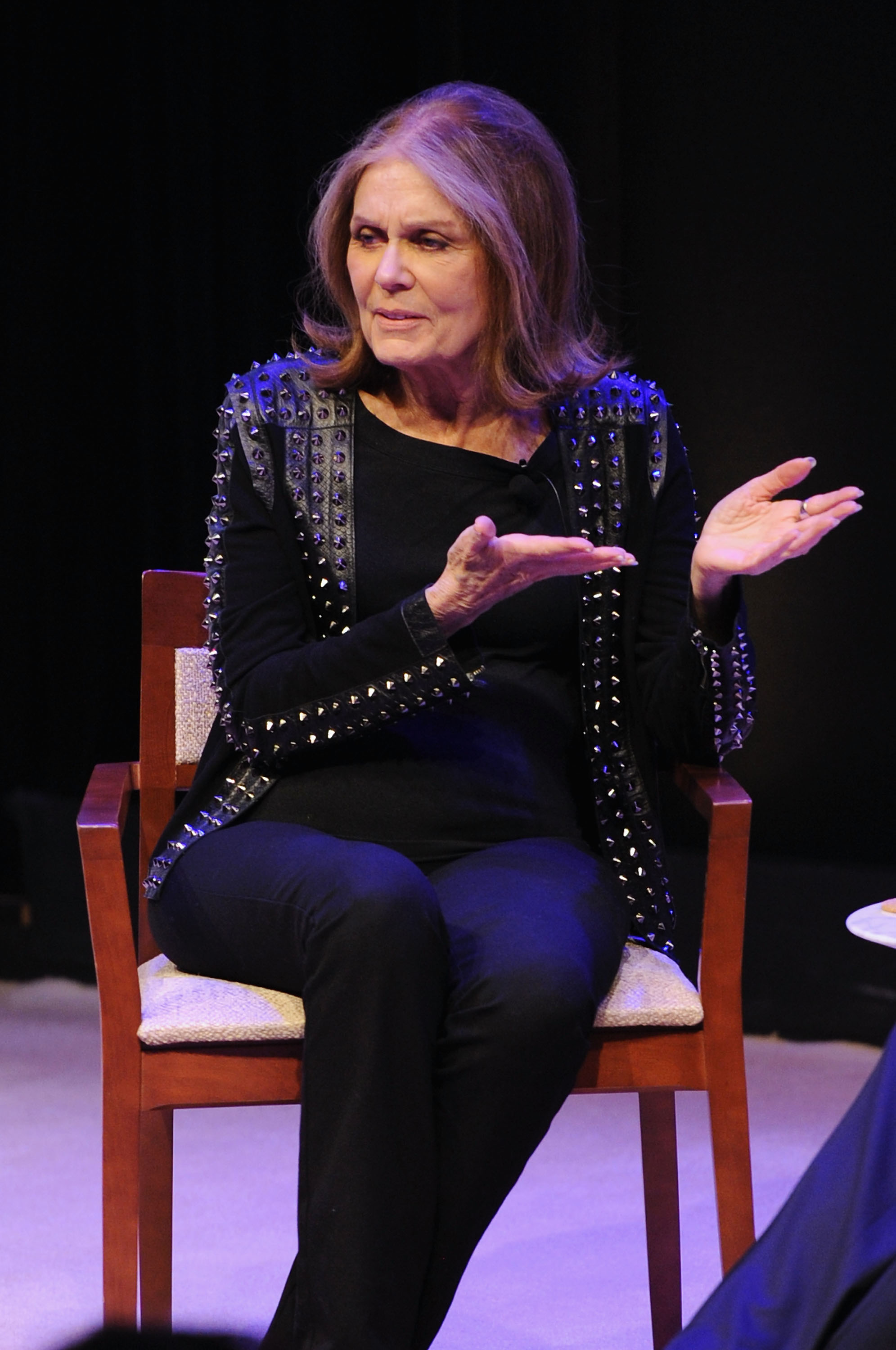

After the Wednesday night premiere of WOMAN With Gloria Steinem, a new Viceland docu-series about violence against women around the world, a young woman in the audience stood up to ask a question. Facing a small crowd that included Meryl Streep, Jennifer Lawrence, and Mariska Hargitay, the woman, who didn’t identify herself, began to cry.

She was an aid worker who had spent years working in the Democratic Republic of Congo, she said. She was crying because someone was finally paying attention to the mass rapes that were happening to women there.

Gloria Steinem asked the woman about her organization. She described the work they did but didn’t offer the name. “No,” Steinem said, “What’s the name of it? So people can help.” The woman quietly said the name of her organization, but it escaped the ears of this reporter.

Steinem has long been the grand dame of modern feminism precisely because of moments like this: she is unfailingly supportive of other women down to the most casual gestures, like helping a nervous young aid worker effectively pitch her organization to a room full of people. She once famously offered an extra room in her apartment to a young woman who needed a place to stay in New York City. Which is why many women found it so jarring in February when Steinem told Bill Maher that young women voters supported Bernie Sanders because “the boys are with Bernie.”

That comment, she tells TIME in an interview, was taken wildly out of context. “I didn’t understand that he had taken it a different way, otherwise I would have stopped him,” she says. “I was just talking about how angry young women were that they were graduating in debt. But the second part of the sentence got cut out.”

She calls the backlash to her comments “an ass kicking,” but says she understands why young women reacted the way they did. “If I had only said what the Twitter-length version said I’d said, I’d be mad at me too,” she explains. “It was very frustrating, to put it mildly. Especially because if you’d been saying the same thing for years, you can’t believe that people think you think what you don’t think.”

Even at 82, Steinem says the experience taught her something: “It made me understand the dangers of excerpting a few words.”

But it hasn’t kept her from continuing to voice her support for Hillary Clinton, especially in the face of Donald Trump as the presumptive GOP nominee. “What’s important about [Clinton] is not only that she’s walked around all her life experiencing life as a female human being, but also that she represents the needs and issues of a majority of women and men,” she says. “If she loses, it will mean that the majority either did not vote, or is prevented from voting.”

Younger women, who criticized Steinem over her Bill Maher comments, are key to Clinton’s success, she says. “I’m greatly encouraged by, inspired by, admiring of younger women,” noting that she admires how young women have elevated the issue of campus sexual assault and work to remove the taboo from topics like menstruation. And despite the fact that young women seemed lukewarm about Hillary Clinton throughout the primary, Steinem says she thinks women are actually more likely to vote for a woman candidate than they were in the 1970s.

“In the ’70s, the firm belief of many people in politics was that women would not vote for other women, that it was a negative,” she says. “We’re all more likely to be raised by women, so we associate female authority with childhood and emotionality … We have not been allowed to associate authority outside the home with being female. Now there are many more women who will vote for a woman than ever before, but there’s still the real-life situation that it’s hard for us to imagine female authority at the highest level.”

And then there’s Trump, who makes Steinem “as shocked and angry as you can imagine.” She says the movement that made Trump the presumptive Republican nominee is a “backlash” to the social changes happening in this country, but she sees his rise as an encouraging piece of evidence about how far the country has come.

“If we hadn’t had a frontlash, we wouldn’t have a backlash,” she explains, adding that Trump supporters are overwhelmingly white and male, and “resentful because they feel privilege has been taken away from them.” “The force of the backlash is in some ways a tribute to the success of the frontlash,” she says. “That doesn’t mean the backlash will win.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com