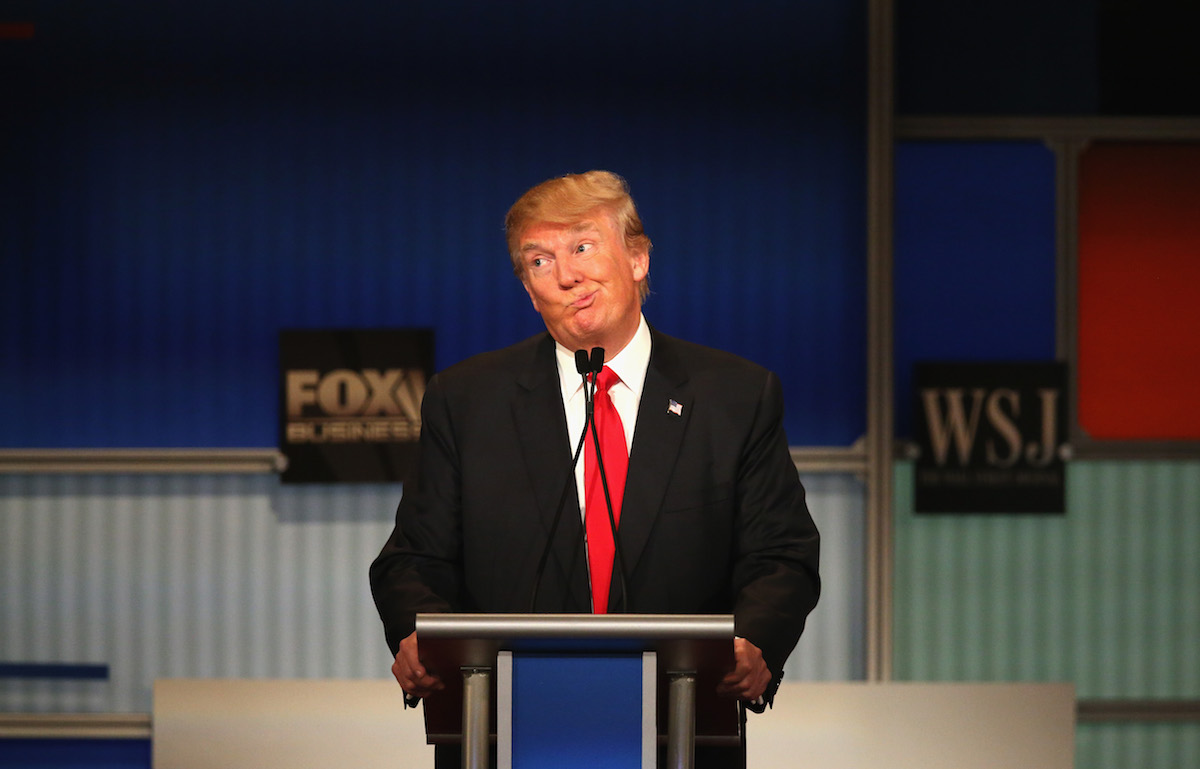

The news on Tuesday that the Rolling Stones have asked Donald Trump not to keep using their music at campaign events will come as no surprise to anyone who has followed the recent history politics and entertainment intersecting.

Not only is this not the first time Trump has used the music of the Rolling Stones without permission from the artists, it’s also just one of many examples of an artist complaining about their music’s use for by a political candidate. Musicians such as Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen and Jackson Browne have all spoken up about politicians using their music.

And, despite what can seem like an imbalance, it doesn’t just happen to candidates from the GOP: The Rolling Stones were also upset about Angela Merkel using the song “Angie,” and in 2008 Barack Obama was (very nicely) asked by Sam and Dave to stop using the song “Hold On, I’m Comin’.”

MORE: Running for President? Skip These Songs

People running for President are usually eager to seem law-abiding, but music permissions can be complicated.

As NPR explained in 2012, many places where politicians hold rallies already hold “blanket licenses” to play music for live without individual permissions. (Television commercials are a different story, which is perhaps why fewer of them rely heavily on pop songs.) The other complicating factor is that, even when everything is squared away on the licensing side, a musician can still object to the song’s usage. On a legal side, she may be able to argue that the song’s use for a cause with which she disagrees is tarnishing her brand. Or, even without involving lawyers, a musician could make her views known, on social media for example. in a way that embarrasses the candidate.

As the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP)notes in its guidelines to political campaigns, “It has become increasingly significant for political candidates in the public spotlight to conduct their campaigns within the copyright law.”

Though this antagonism between musicians and politicians isn’t limited the the modern political age—Barry Goldwater had to stop using the tune to “Hello, Dolly!” in 1964, after rival Lyndon Johnson secured exclusive rights to it—the phenomenon does seem to be getting a lot more common.

But why is this happening?

“It’s basically a reflection, for the most part, of the change in the type of music that’s used—and the fact that the technology permits the music to be played very easily without the artist being there,” says Eric T. Kasper, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. “The instances of this have gone up exponentially, accordingly.”

MORE: See Vintage Photos from the Early Days of The Rolling Stones

The technological side is pretty simple to understand. It’s not only easier to play whatever song you want whenever you want, it’s also easier to see who’s playing what. It used to be that a song played at a community lodge that lacked a music license, for example, would only be heard by those at the rally. But when the rally goes up on cable TV or YouTube, the rest of the world—including the person who wrote the song—can find out more easily.

But this is not just a matter of finding out about something that’s been going on forever.

As explained by Don’t Stop Thinking About the Music: The Politics of Songs and Musicians in Presidential Campaigns, which Kasper co-wrote with Benjamin S. Schoening, it was in the mid-19th century that candidates figured out they would do well to use music, which spread quickly and required no literacy skills, to attract voters. Even so, the songs used by those candidates were usually written—or at least modified—for specific use by the candidate. These were like jingles, setting campaign promises to music, rather than pop songs that blared to amp up crowds. The first presidential candidate to have his campaign notably associated with an already-popular song was Franklin Roosevelt, who used “Happy Days Are Here Again” in 1932. Kasper and Schoening argue, however, that the world events that followed FDR’s election prevented that decision from becoming a trend, as the catchy music would not have been appropriate for the times.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that political music entered what the authors call the “pop era.” In the decades just before, the scope and role of popular music in America had changed. And, as music historian Robert Greenberg has pointed out, the sound changed too: it was easy to change the words to Frank Sinatra’s “High Hopes” to be about JFK, but a rock song was less malleable. As a result, politicians wanted to play the original recordings.

As the age and demographics of the voting population changed, the people who were used to the music of the 1960s and ’70s—baby boomers—became a more important voting bloc. It’s no coincidence that Ronald Reagan’s use of Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” often comes first in lists of conflicts between musicians and politicians. (He was able to use Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” at the 1984 convention without trouble, though.) Nor is it a coincidence that Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign use of “Don’t Stop (Thinking About Tomorrow)” is often cited as an early major success in this field: Clinton was, after all, the first baby-boomer President.

Even as new generations come to power, Kasper sees the trend continuing. Kasper says that, legally, artists have more recourse than ever—though the “implied endorsement” claim many many has yet to be tested in court, to his knowledge—but that campaigns are unlikely to stop using the pop songs they like.

“What counts as popular music and what will appeal to potential voters, that’s going to switch,” Kasper says. “We see some of that already. But it’s going to be a while before we switch to something beyond pop music as the main music used in these kinds of campaigns.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com