It’s midday in Porto-Novo, Benin. The sun is at its high point in the small agricultural village as a man flies across the dirt roads on a 100cc motorbike, leading 20 other riders. It would be harmless, save for the eight handmade containers holding up to 53 gallons of gasoline strapped to the vehicle which, if it crashed in the village, would trigger a chain reaction that could kill hundreds.

Today, nearly 150,000 barrels of gasoline are pilfered each day to feed the illicit trade, supplying more than 75% of gasoline that Benin consumes. Beninese traffickers buy petrol in Nigeria, where it is cheaper. They sell it in roadside stalls around the entire country at sometimes half the usual price.

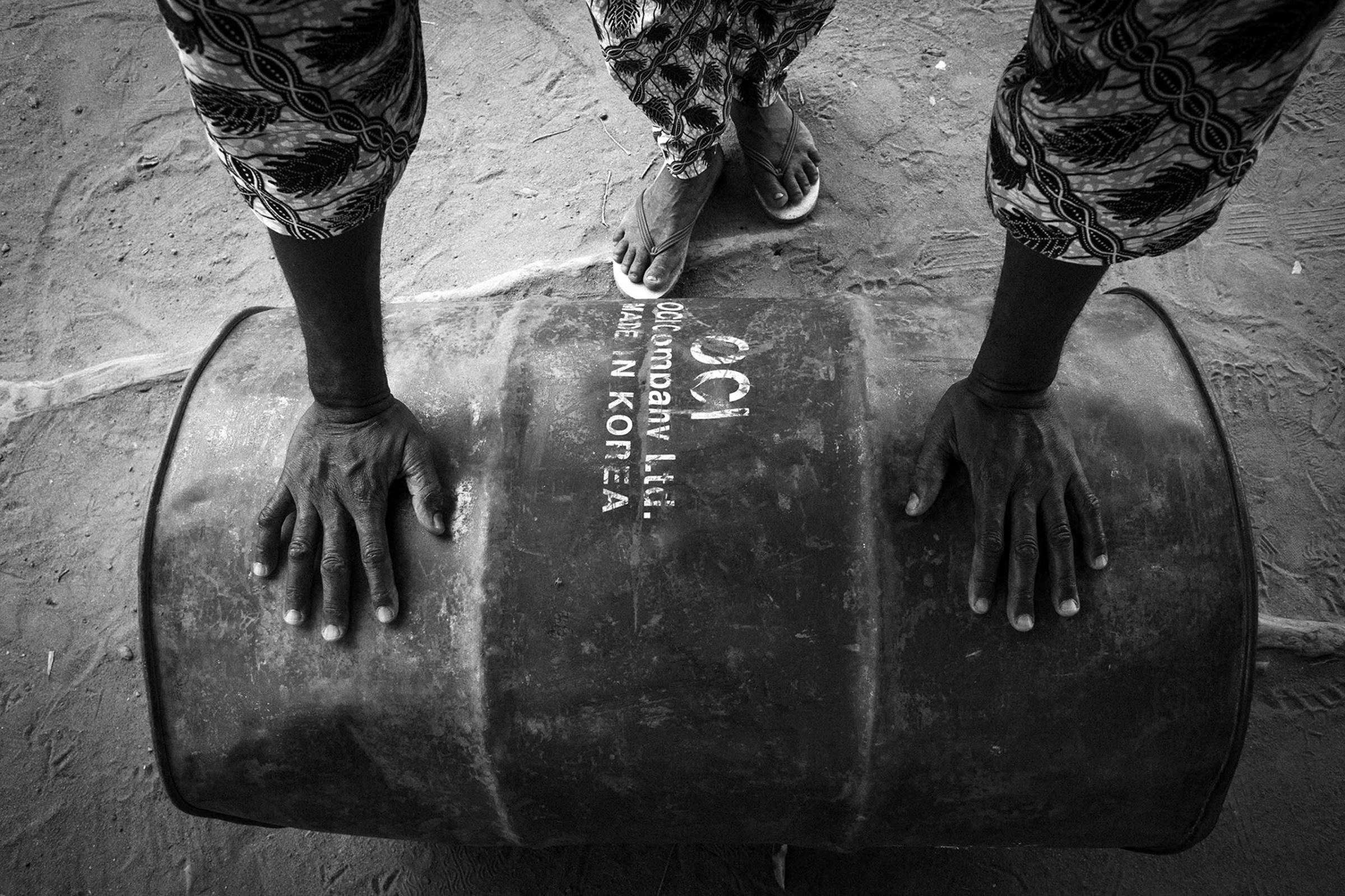

Spanish photographer Javier Corso traveled to Benin to investigate the vast network of gasoline smuggling from Nigeria to Benin. His photo essay, Essence du Bénin (gasoline, in English), is part of the first venture for the newly launched Oak Stories agency—a collaboration with journalist Neus Marmol and videographer Lautaro Bolaño.

Corso followed Kamikazis or human bombs, as they are called, from the Nigerian gas stations; to the road or lake as the fuel was transported; all the way to the stations manned by women and children in Porto-Novo, Benin.

Corso’s high contrast black-and-white images offer an unfettered glimpse into the day in, day out of Beninese citizens living in a poor agricultural country with high unemployment rates. Many who work in the fields depend on additional employment to feed their family. With few other alternatives, illegal trafficking of petrol is necessary to survival. “We cannot wipe away this illegal trade without starving thousands of families in Benin,” Marmol tells TIME. “The problem is so intertwined with all parts of the population that to end it overnight would both paralyze the nation’s economy and spur a revolution.”

Javier Corso is a documentary photographer based in Spain. Neus Marmol is a producer and journalist. Both are founding members of OAK Stories Agency.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com