In New York City last month, I was walking down Columbus Avenue when I stopped short in front of a billboard for the high-end fitness chain Equinox. It pictured a shouting, half-naked young woman, her chest painted with the circle-and-cross symbol universally understood as “female.” Her fist was clenched in protest, though what exactly she was demonstrating against was unclear—in the background, some distance behind her, a small phalanx of suited male figures guarded the steps of what looked to be a museum or a government building.

“COMMIT TO SOMETHING” commands the copy that stretches from one end of the image to the other, and below that, in smaller text, is the gym’s tagline: “It’s Not Fitness. It’s Life.”

What’s this mystery woman’s cause? Ten years ago, amidst a growing drumbeat of climate-change awareness, she would have been an environmental crusader. In 2016, all we need to know is that she’s a feminist. Well, that—and that she’s in great shape.

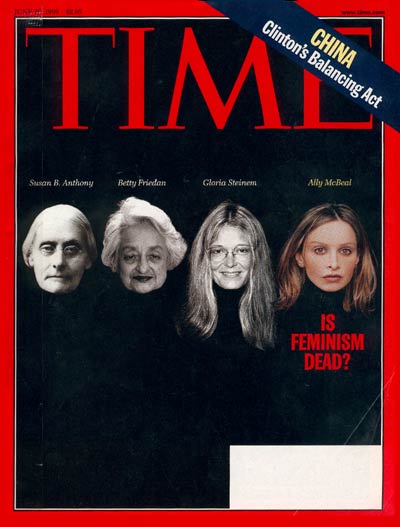

For someone who has spent the past 20 years studying and writing about feminism’s long, symbiotic and often combative relationship to media and pop culture, the past few years have been a revelation. For decades, feminists and feminism were almost exclusively evoked by newspapers, magazines and punditry as an ideological punching bag; TIME’s 1999 cover blared “Is Feminism Dead?” using an image of pouting, miniskirted TV lawyer Ally McBeal to tacitly answer in the affirmative. These days, the word is deployed with a breathless thrill of zeitgeist, whether the topic is advertising (CoverGirl’s #GirlsCan campaign), celebrity culture (Taylor Swift! Emma Watson!), or electoral politics (play that woman card, Hillary!). Feminism, for better and for worse, has become trendy.

The moment when feminism broke into mainstream America like the Kool-Aid Man busting through a wall was arguably Beyoncé’s 2014 performance at MTV’s Video Music Awards, where she struck an indelible pose in front of huge neon letters spelling out the word “FEMINIST” as she quoted Nigerian writer Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie. But that moment didn’t come out of nowhere: it happened as part of a groundswell of awareness that had built over the preceding two decades via zines, blogs, grassroots organizing and social media—as well as via current events that brought intrinsically feminist ideas to audiences who’d only heard of feminism as something that came and went in the 1970s.

The are positive benefits to feminism’s rising profile. Take the high-school rape case in Steubenville, Ohio, for instance, which brought the concept of “victim blaming”—something that had percolated in feminist discourse for decades—into view. Or consider the Bechdel Test, a measure that looks at whether two women in a film speak to one another about something other than a man, which we now see referenced in film and TV criticism. And don’t forget Bill Cosby: it’s not a coincidence that the combination of feminism activism and social media was what finally brought down an alleged predatory comedian who’d been operating in plain sight for decades.

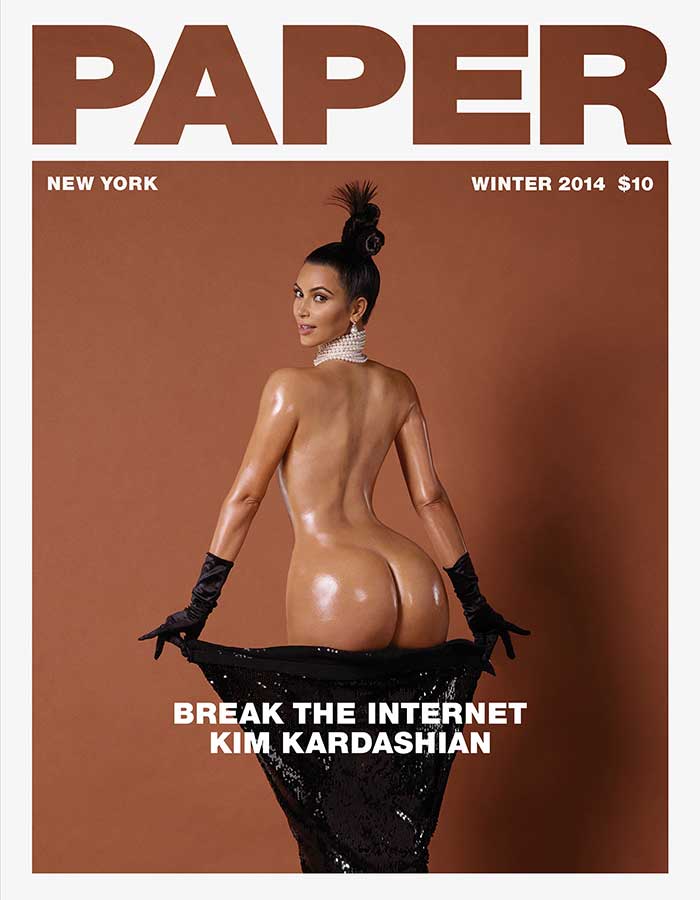

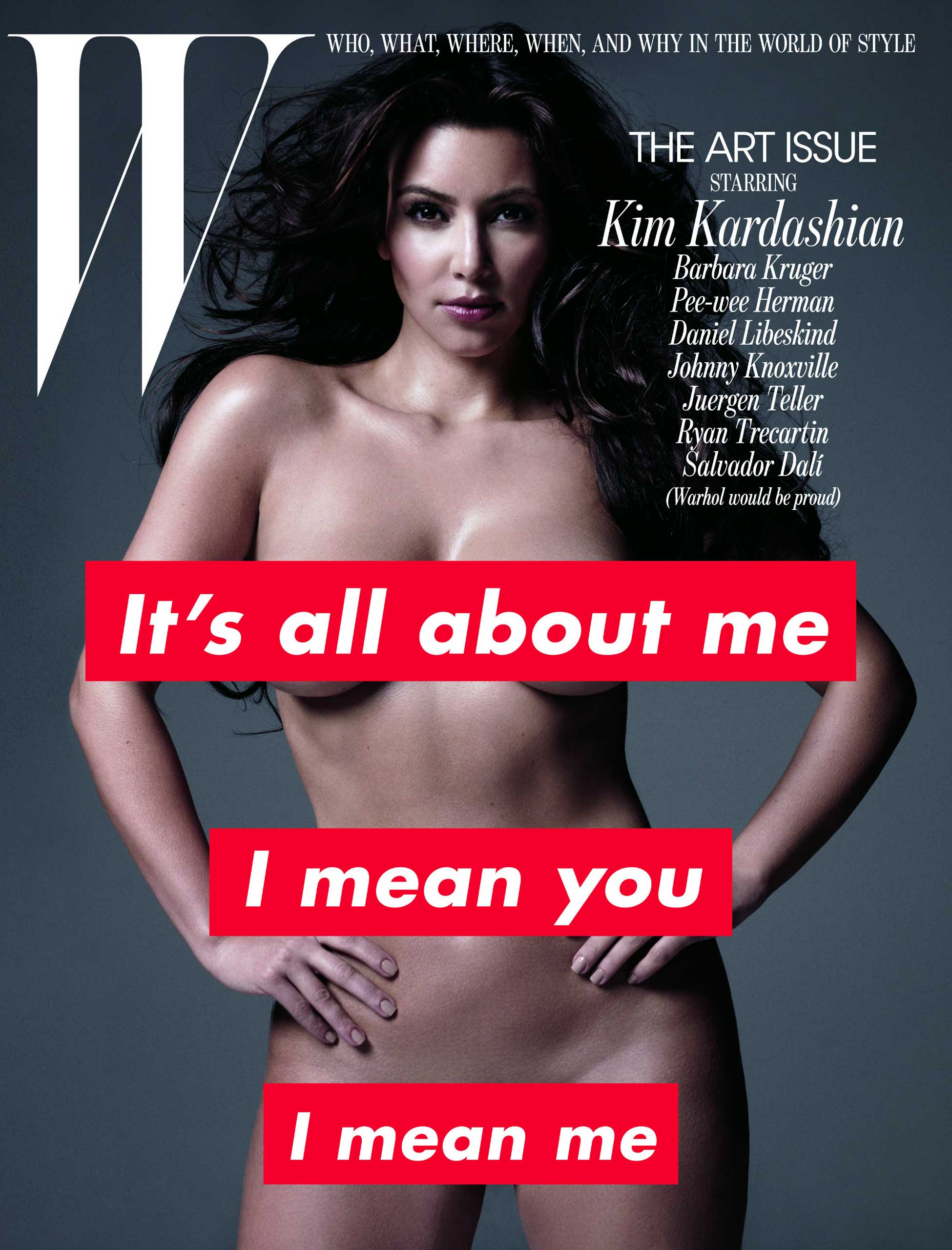

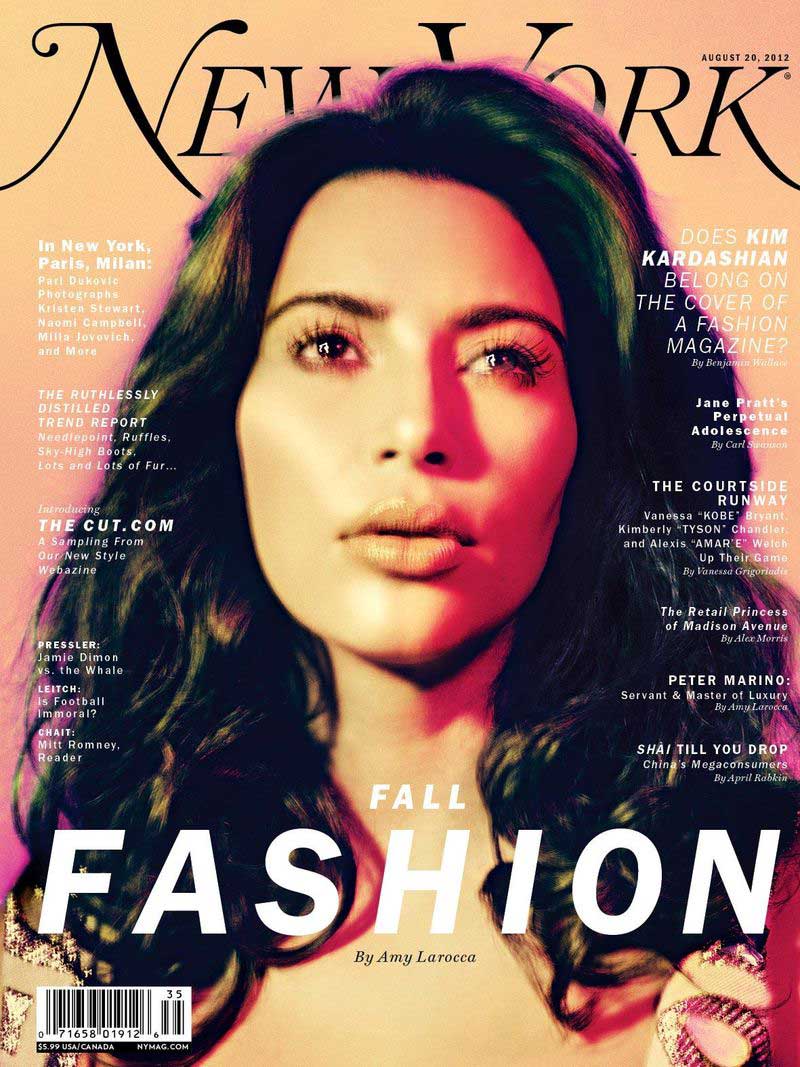

And yet feminism’s recently skyrocketing profile is a reminder that the best way to constrain the power of a social movement is to commodify it. Just ask Dove, or Verizon or Always, brands that in the past few years have seemed to suddenly realize that flattering women with overtures to and images of female empowerment could offer a better return than classic ad tactics of appealing to feminine shame and insecurity. Ask Kim Kardashian, who hijacked the coverage of International Women’s Day—a day meant to draw attention to women’s economic, social and political status worldwide—with a blog post about a nude selfie that she universalized into a grand statement of body pride.

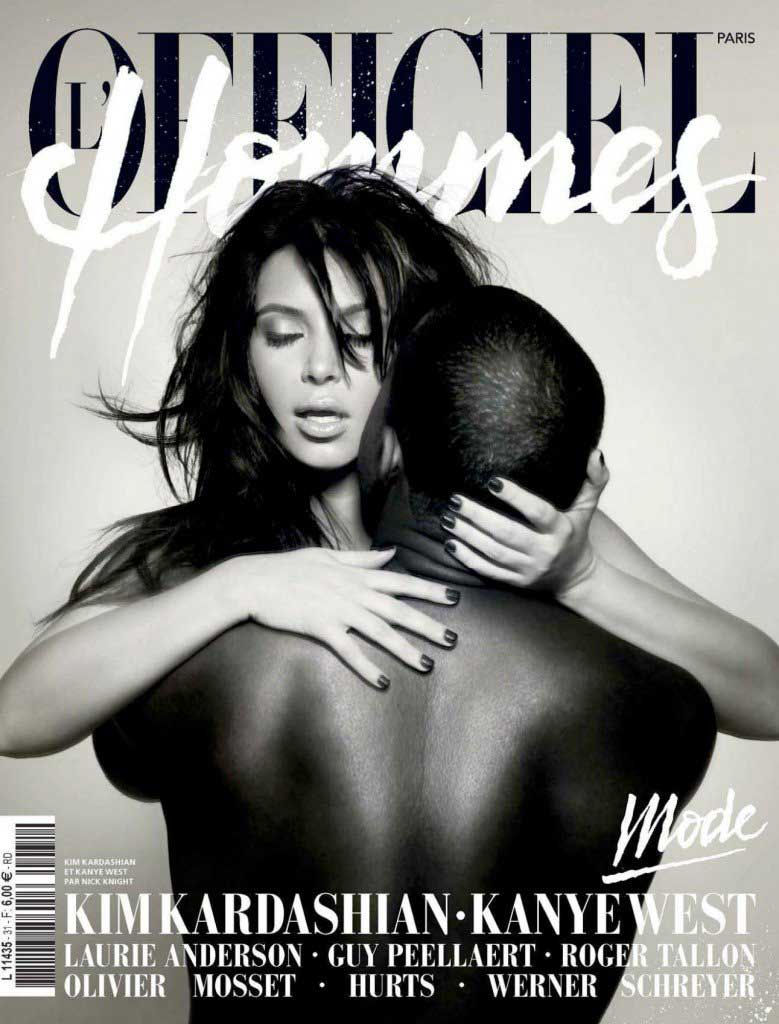

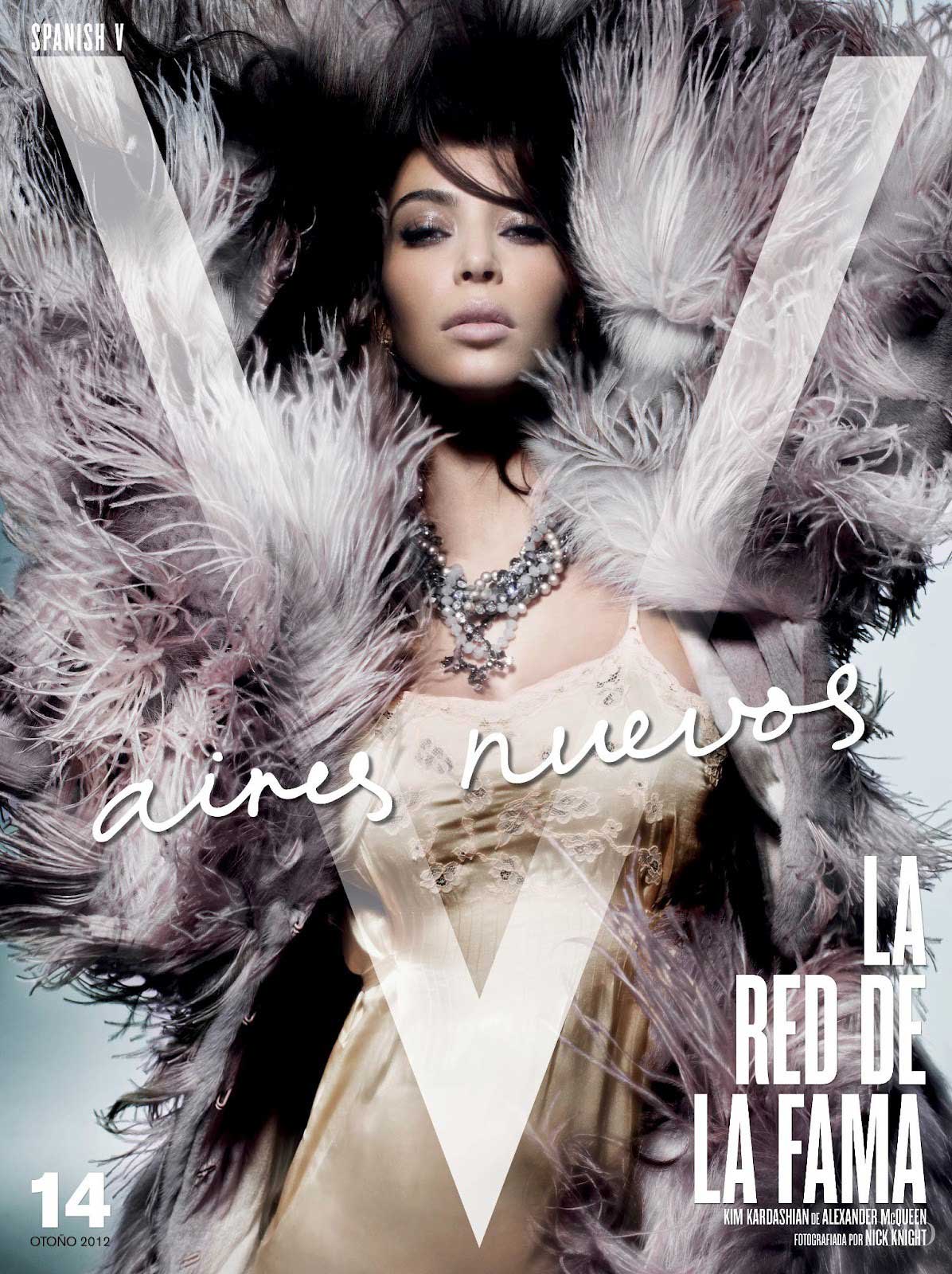

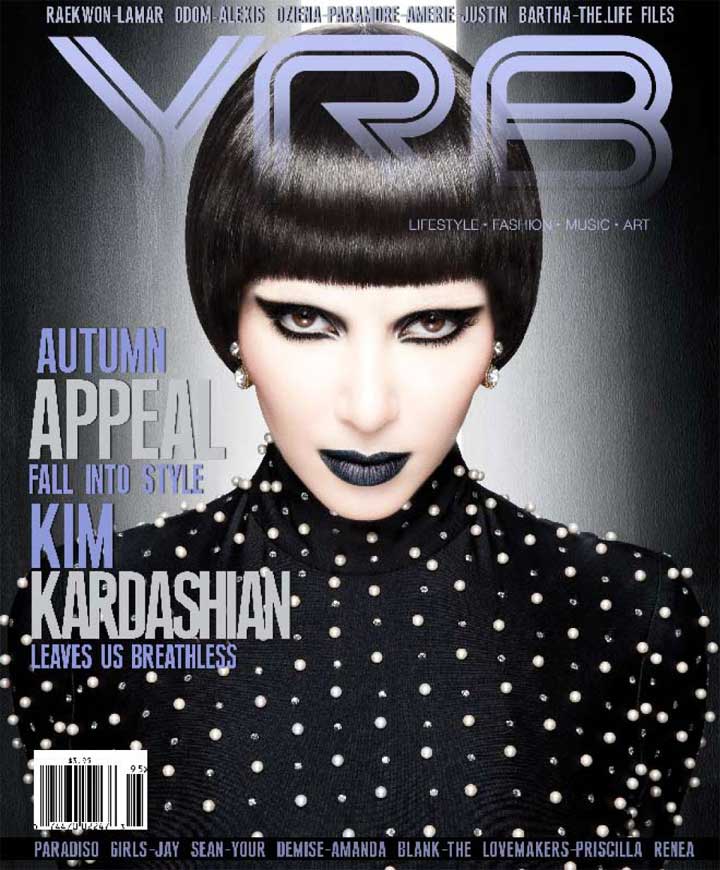

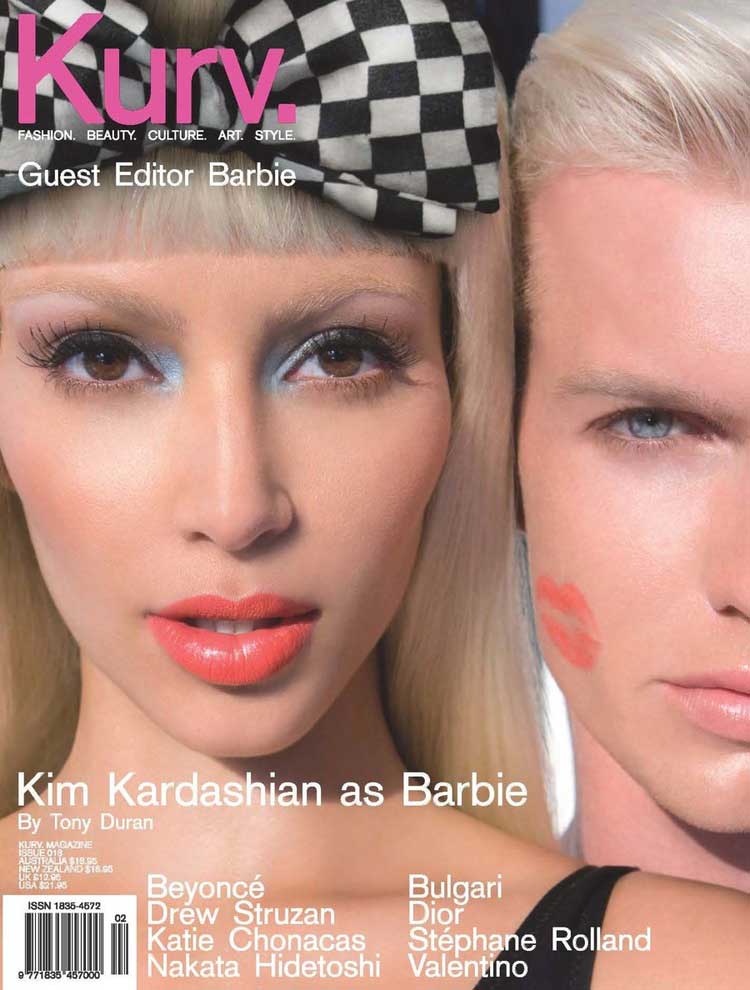

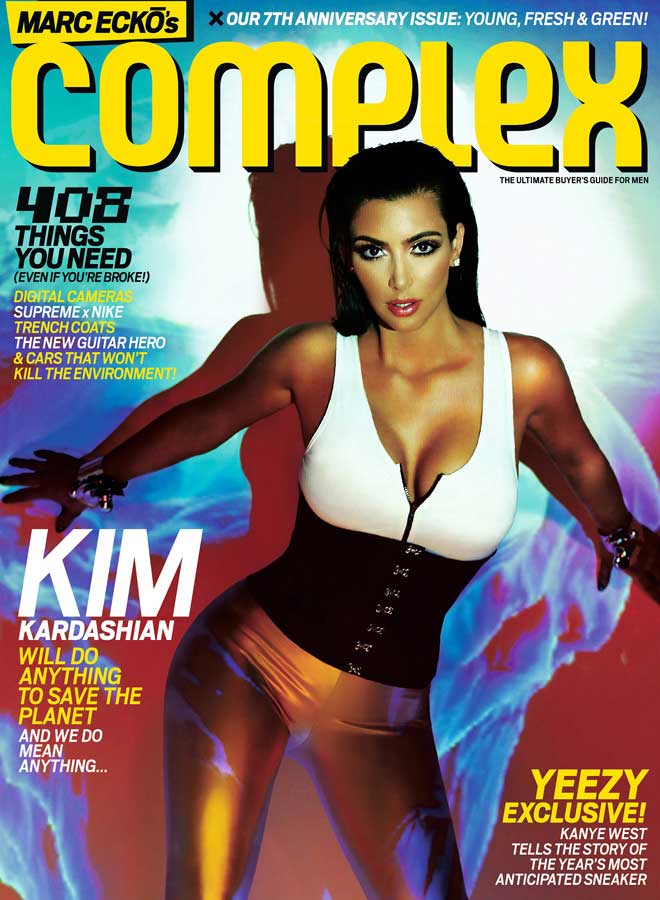

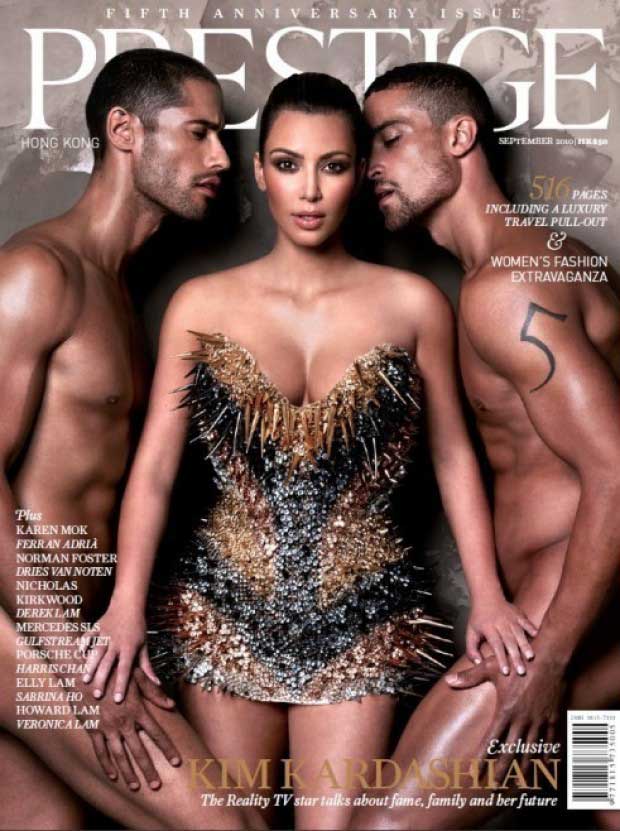

See Kim Kardashian's Most Memorable Magazine Covers

This kind of marketplace feminism is welcome not just because its optics are considered a media-friendly improvement on past feminist movements—more cleavage, less anger—but also because it draws focus away from the systemic and places it firmly in the realm of the individual and the personality-driven. It’s easy to see Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg, for instance, urging women to lean in, and forget that leaning in puts the onus on women themselves—rather than on the corporate systems and values that shortchange all workers regardless of gender. It’s equally easy to nod along with Taylor Swift (or Madeleine Albright, for that matter) referencing that special place in hell for women who don’t support other women and assume that we’ve got the basic tenets of gender equality squared away. A look around the country at everything from the state of reproductive rights to the language of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign confirms that we don’t.

What does it mean when a movement that is fundamentally unfinished is fashioned into a trend, a commodity, something to put on and/or take off at will? Marketplace feminism isn’t new: For as long as there have been feminist movements, Madison Avenue, Hollywood and more have been there to co-opt and cash in on them. But there’s a difference between making feminism attractive and making it meaningful to the millions of people who are more worried about earning a college degree or a living wage than they are in angling to get a heel into the C-suite. The appeal of marketplace feminism is that it doesn’t ask much of consumers.

But to make the world itself more feminist—safer, saner, more equitable, more sustainable—requires asking more of each other and ourselves than the market can answer. It involves asking difficult, complex and uncomfortable questions about what and who we value. It requires confronting the reality that the world has not evolved nearly as much as we’ve been led to believe it has. It needs us to admit that making us feel good about what we buy is not the same as making us feel purposeful about what we do. If we’re going to follow Equinox’s lead and commit to something, I propose we start with that.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com