Given the opportunity he was presented—a candid conversation with the Attorney General of the United States—federal prison inmate Tony Moses took a chance.

“I could get a call tomorrow saying that, ‘Hey, Moses, the Attorney General says let you go,’” he said. “Just thought I’d throw that out there.”

It could have been an awkward moment, but the Attorney General kept it light. She and the Bureau of Prisons staff that joined her on her mid-morning tour of the Federal Correctional Institution at Talladega, let out friendly laughs. “Now wouldn’t that be a call,” Attorney General Loretta Lynch said.

Moses, whose official “out date” is 2041, was one of five inmates selected to join the Attorney General for a round table discussion about their experiences in the prison. Each sat in cushy blue chairs arranged in a half moon shape at the center of the brightly lit, white tiled room at the sprawling Alabama facility. Two ferns were placed on either side of the chairs, nestled at the base of white painted pillars. Lynch sat before them in her own blue chair, positioned close enough to keep the dialogue intimate, but just far enough to send a clear message: before you sits a very important person.

Hallways and entryways staff members regularly pass through make it clear that she’s the boss. A framed portrait of the AG sits just below a portrait of President Obama on the walls of several FCI Talladega corridors. But from the fences to the multiple security rooms one has to pass through to enter and exit them, you get a sense the over 900 inmates housed in the medium security facility there don’t get the opportunity to see Lynch’s face on those walls. The average sentence in the prison is 174 months. Forty-two percent of the inmates are imprisoned on drug charges, 33% are in for weapons crimes, and another 8% are immigration offenders.

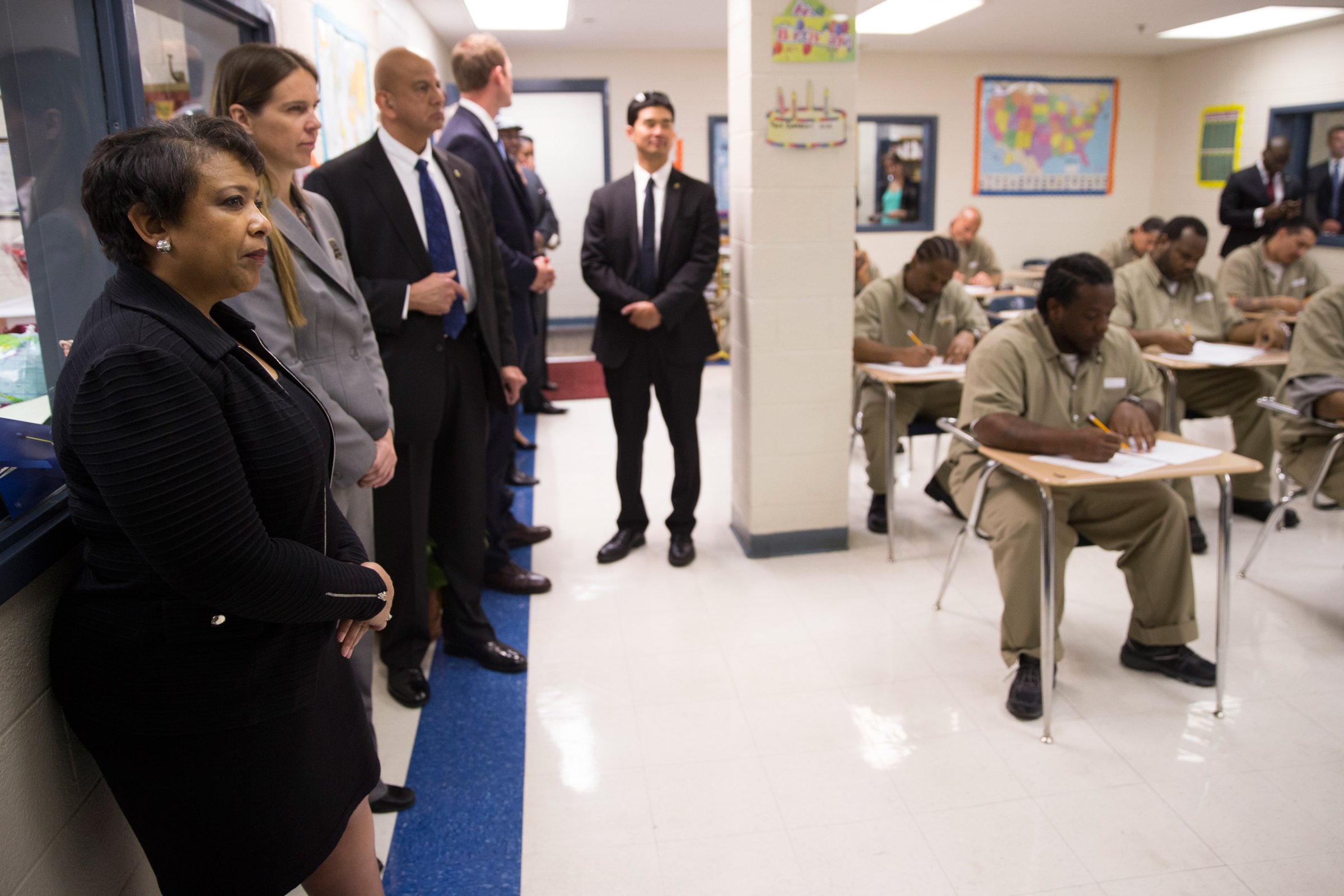

Before the roundtable discussion, the Attorney General experienced firsthand some of the programs available to inmates in the prison. She stopped by a GED class where 12 students were studying arithmetic. She walked the floor of a UNICOR facility where her presence induced a temporary stay of production. As she exited, the inmates stood and applauded—before getting back to work. In UNICOR, one of few remaining in federal facilities, the inmates are paid for what they produce, which in this case is military uniforms.”Driving toward reentry one down at a time,” a wall of the warehouse is painted to read. Below it, a football field with “reentry” painted in the endzone. Just outside of the field, “team” helmets with words like “UNICOR” religious services” and “rdap,” sit where a team logo would on a regular helmet. This is a prison; the goal is to get out.

“I’m happy to meet you all here, but I don’t want to come back to see you,” Lynch told inmates at the roundtable discussion. “Unless you’re just about to leave. That’s the only time.”

The tour of FCI Talladega culminated a week’s worth of events and announcements from the Obama Administration marking “Reentry Week,” which highlighted programs and policies in place to help returning citizens better adjust to life outside of prison. As TIME has reported, the adjustment from life in prison to life outside can be stressful. Former inmates face issues ranging from the overwhelming number of toiletries available for purchase to securing stable housing and employment. The administration announced a number of steps they’d taken to reform re-entry this week, including a request that governors make it easier for returning prisoners to gain ID cards. On Friday, the White House announced a plan to “ban the box,” or prohibit questions about federal job applicants’ arrest histories until the final stage of the hiring process.

It was on the heels of that announcement that the Attorney General toured FCI Talladega, where she also sat in on a drug recovery program and spoke to inmates undergoing treatment.

The roundtable provided for the most intimate discussions. Lynch prodded inmates about their experiences in programs, their families, and how prepared they feel for life outside–no matter how far off that may be. Each shared personal tidbits. An inmate named Eric Milton bragged about his nephew who had just sent graduation photos from Florida A&M University. Milton told reporters after that he has applied for federal clemency. Another, Frank Yonker, gabbed with Attorney General about being a grandfather. They hope the experience, they said after, helped Lynch realize their humanity.

“Just because we’re in here doesn’t mean we’re bad people. We just made some bad choices,” said Moses, who is in prison on armed bank robbery charges. “We’re still human.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com