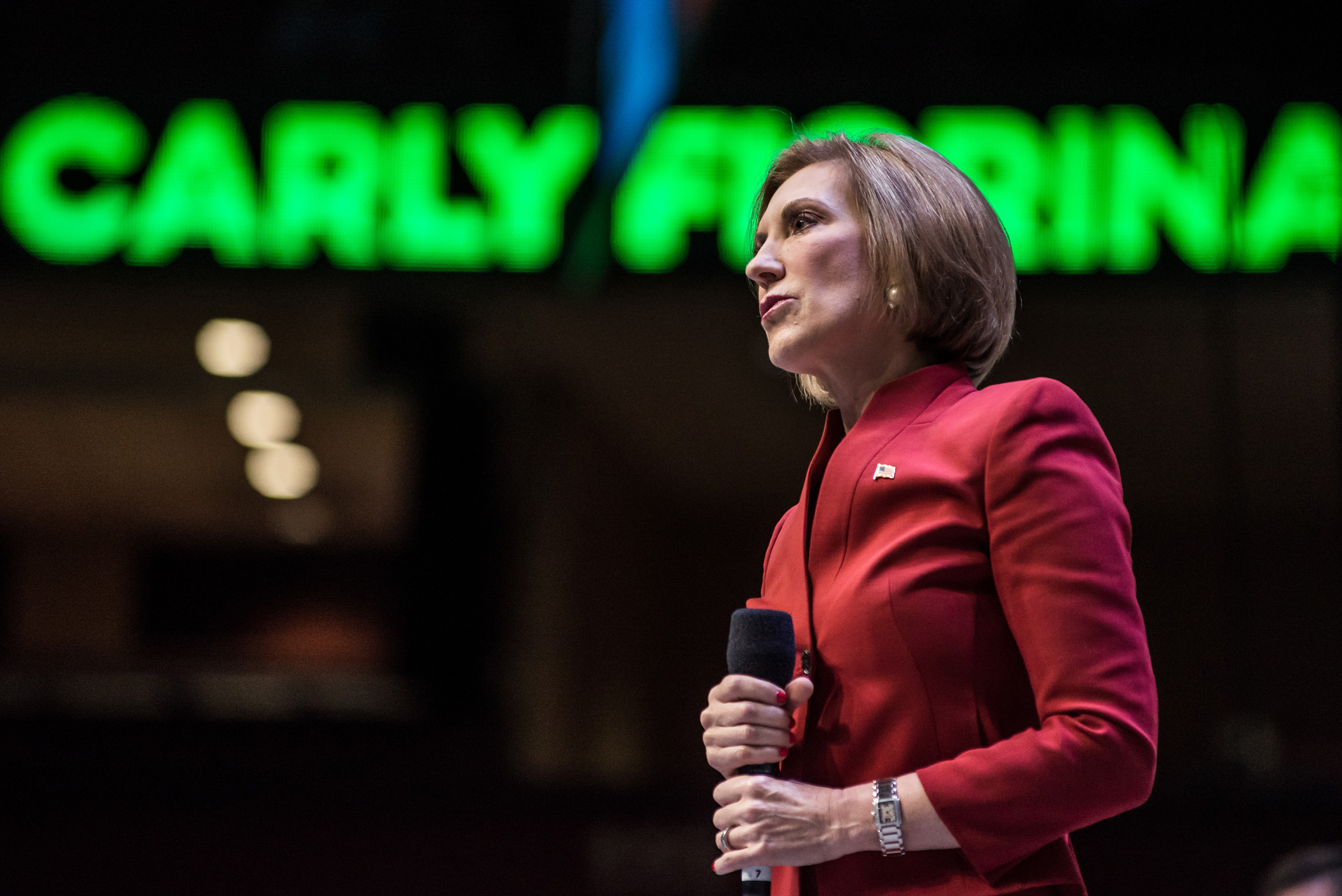

The news that Ted Cruz will select former rival Carly Fiorina as his running mate should he win the Republican nomination for the presidency means that Fiorina would join an elite group. The list of women who have been nominated for vice president by a major U.S. party numbers just two: Geraldine Ferraro, who ran on the Democratic ticket with Walter Mondale in 1984, and Sarah Palin, who ran with John McCain on the Republican ticket in 2008.

But not that long ago, when Ferraro was first introduced to TIME readers in 1978, as she sought a seat in Congress, it was with a sadly familiar trope: she was frying eggs for her family’s breakfast, trying to be a “good mother and wife” while doing something that “few women in Queen—or elsewhere—have considered.” More than a decade of feminist activism had only produced a relative handful of women in Congress.

The reasons for the lack of progress were many. Women lacked an in at the literal old-boys’ clubs where politics took place, they tended not to have union support and they had trouble raising money because they were seen as unelectable. (As TIME pointed out, there’s a vicious cycle at work with that last component: raising less money actually can make a candidate less likely to be elected.) And, just as importantly, old stereotypes about women’s proper roles were still very much in play. Case in point: Ferraro frying the eggs.

So what changed between 1978 and 1984?

For one thing, putting a woman on a major ticket had started to seem like what DNC political director Ann Lewis called “the logical next step.” Lewis wasn’t just talking about making strides for women; she was also talking about the logic of politics. Women making up slightly more than half of the population wasn’t new, but by the early 1980s they were turning up on Election Day just as often as men were and, among some age groups, more often. And though there were still far fewer women in elected office than would have represented their share of the population, there were a couple of high-profile women (like Ferraro) who would be possibilities. More philosophical observers posited that the post-Vietnam War world had soured on masculinity. Meanwhile, as President Reagan’s popularity among women suffered during his first term, many women—especially Democrats—were starting to feel their specific needs did make them a “special-interest group” worth acknowledging when he was up for reelection.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

And secondly, there were the specific needs of the Mondale campaign. In the run-up to that summer’s nominating convention, Mondale’s candidacy was seen by some as unexciting and stale. (TIME said that June that his campaign “so far has sounded like a large, heavy suitcase being tumbled, slow motion, down an interminable flight of stairs.”) Analysts guessed that if he got to the point of selecting a VP and was polling close to the incumbent Reagan, he would make a safe bet to select a man whose home state might swing to the Democratic side; if he were lagging, he would cross his fingers and pick a woman, in hopes that the history-making angle would inject some interest into his campaign.

Ferraro herself admitted that she knew she was being considered primarily because of her gender, but said she didn’t think that meant she couldn’t do the job. It was Ann Lewis, once again, who summed up the feeling among Ferraro’s supporters: “Your token,” she said, “is my pioneer.”

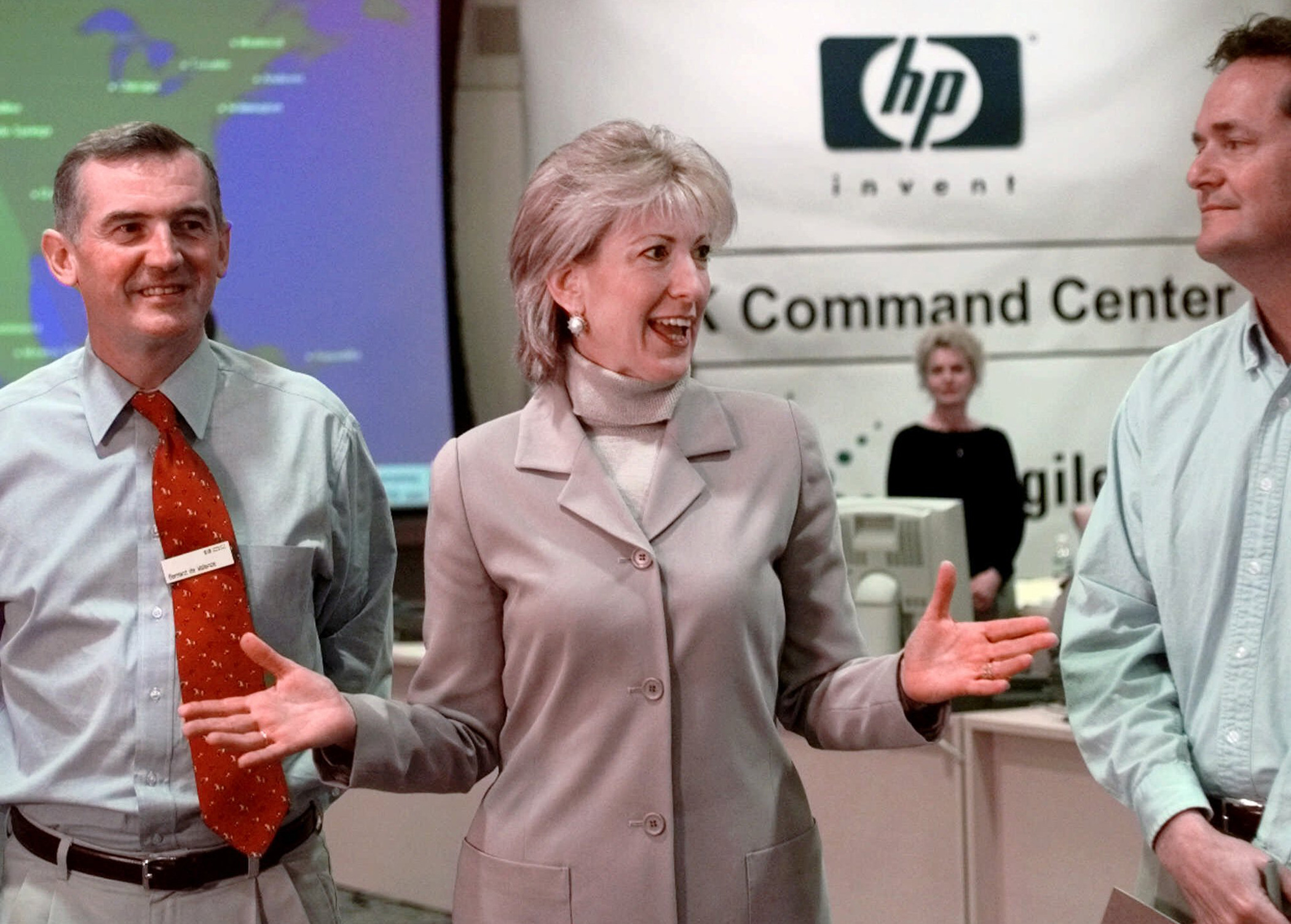

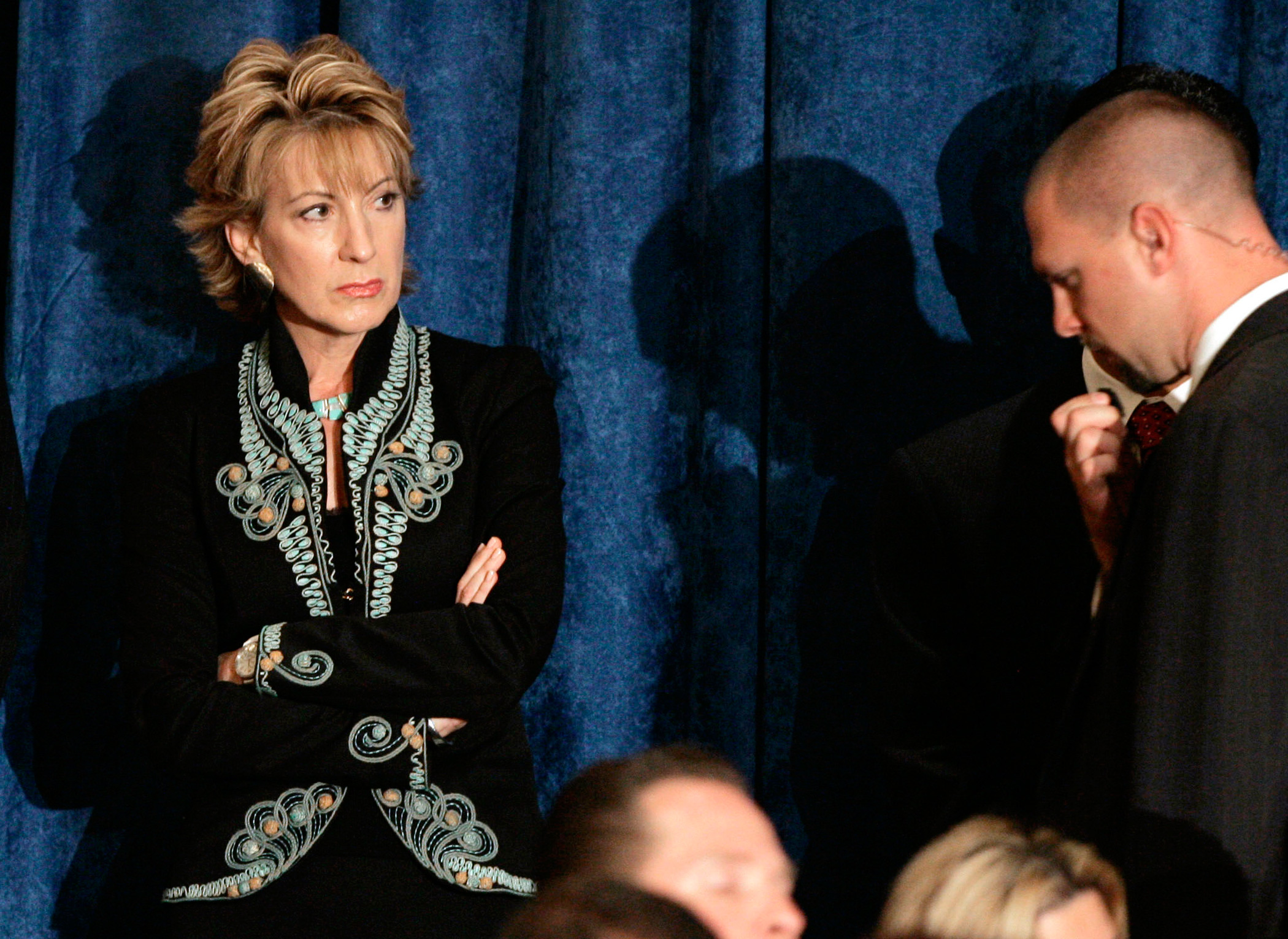

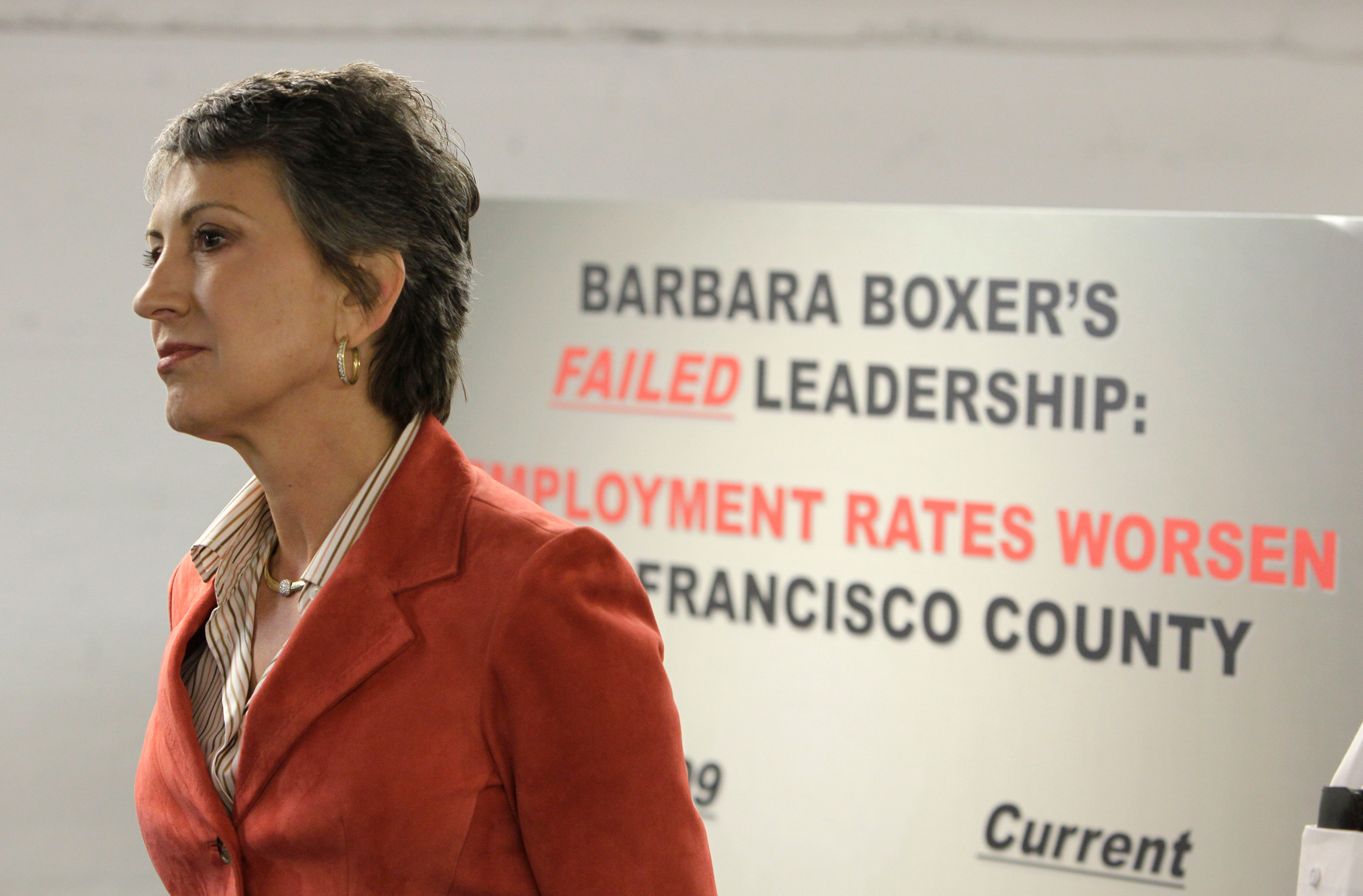

See Carly Fiorina's Career in Photographs

And sure enough, the choice of Ferraro did earn headlines and accolades for the Mondale campaign. The headlines didn’t pay off on Election Day (especially after Ferraro’s husband’s finances became a distracting scandal) but, from the beginning, her supporters had said that she would be be a successful symbol of progress even if she were a failure in that particular race. After 1984, though any number of pros and cons might figure into the choice of a running mate, the first step had been taken. Win or lose, Ferraro had broken a significant barrier.

That’s a feeling that is likely familiar to Fiorina. When she was mentioned in the pages of TIME, in 1999, it was thus: “Pay no attention to the noise, Carleton (Carly) Fiorina was saying last week, as she was crashing through the highest of glass ceilings to become the CEO of computer maker Hewlett-Packard. Although her appointment has not been so ballyhooed as Sandra Day O’Connor’s becoming the first woman Supreme Court Justice or Geraldine Ferraro’s running for Vice President—or, for that matter, America’s women winning the soccer World Cup—it is arguably more important than any of those milestones.”

Read a 1984 interview with Geraldine Ferraro, on being the first woman chosen as a first major-party vice-presidential nominee: An Interview with Ferraro

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com