On the stormy night of Sept. 26, 2014, police from the Mexican city of Iguala pursued a bus full of student teachers, firing shots until it was forced to a halt. The officers then smashed the bus windows with batons and stones and threw in tear-gas canisters to force the students out. When they had them face down and in cuffs, an officer said the detainees wouldn’t fit in the patrol cars. His companion said not to worry, as more police were coming from the nearby city of Huitzuco. Minutes later, three police cars arrived and the students were loaded in — the last verified sighting of them alive.

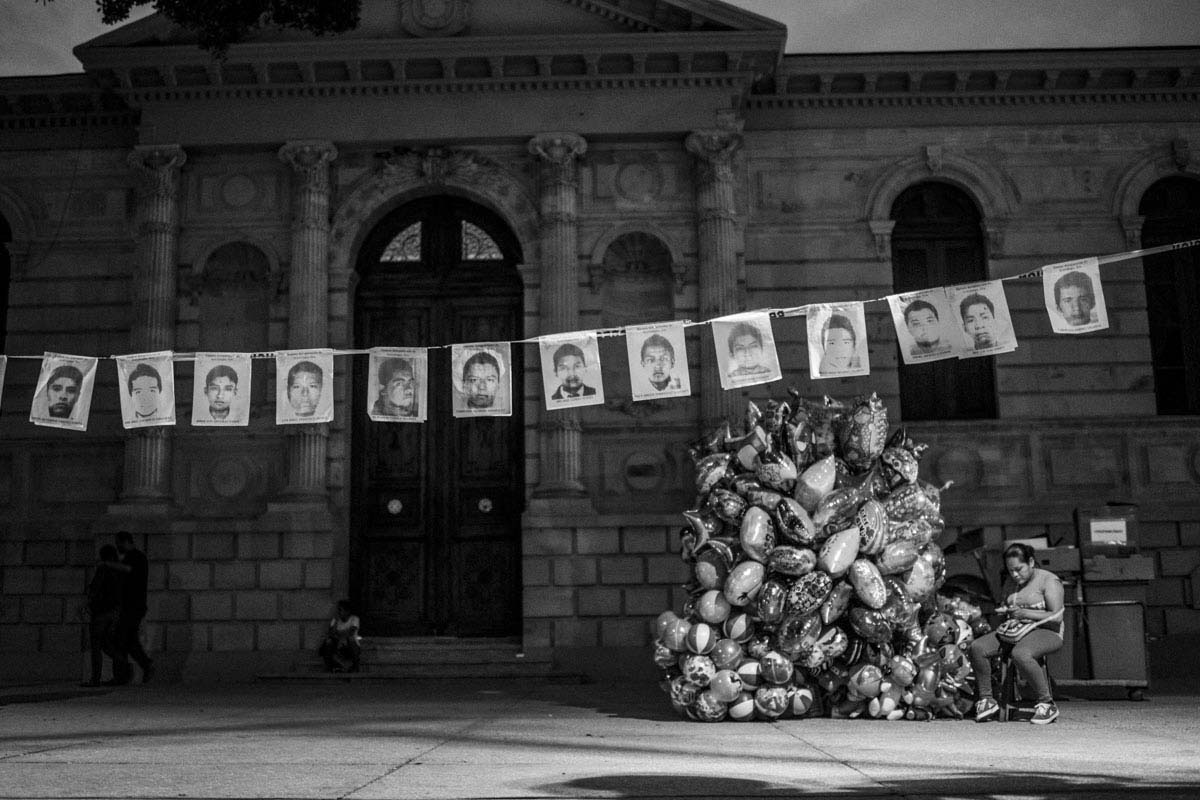

This description of the abduction, given by the bus driver, is among the evidence examined in a new report on the Iguala attacks released Sunday by an independent group of experts, who had been appointed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The 608-page document raises crucial questions about the fate of the students in what has become the most high-profile crime in Mexico in recent years. On that night, a total of 43 students disappeared after traveling on several buses, and another six students and passersby were murdered. Hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets to demand justice following the attacks. Under pressure, the Mexican government agreed to work with the independent experts on the investigation.

The experts’ report, the second they have released, pokes various holes in the government’s case. In 2014, the Mexican attorney general claimed that corrupt police handed students to assassins from a heroin cartel called Guerreros Unidos, or Warriors United. The cartel burned all the missing students at a garbage dump near a town called Cocula, he said. However, the experts argue that evidence shows a fire of the size needed to burn 43 bodies never happened there.

Families of the students have long rejected the attorney general’s account and called on the government to keep searching for the students in other places, including in Huitzuco. More recently, federal investigators have changed their line to say that only some of the students may have been burned at the Cocula dump.

The problems in the investigation have become a central focus of criticism for President Enrique Peña Nieto, whose approval ratings fell to a new low of 30% this month. “For Mexico’s civil society, the case of Iguala has become symbolic of the larger failures in Mexico’s justice system,” says Raul Benitez-Manaut, who heads a think tank on security issues. “In the Iguala investigation, there are cases of torturing of suspects and the mishandling of evidence. These are problems we see everyday in Mexico. The government is failing to confront these issues.”

Confronting Mexico’s Latest Cruel Massacre

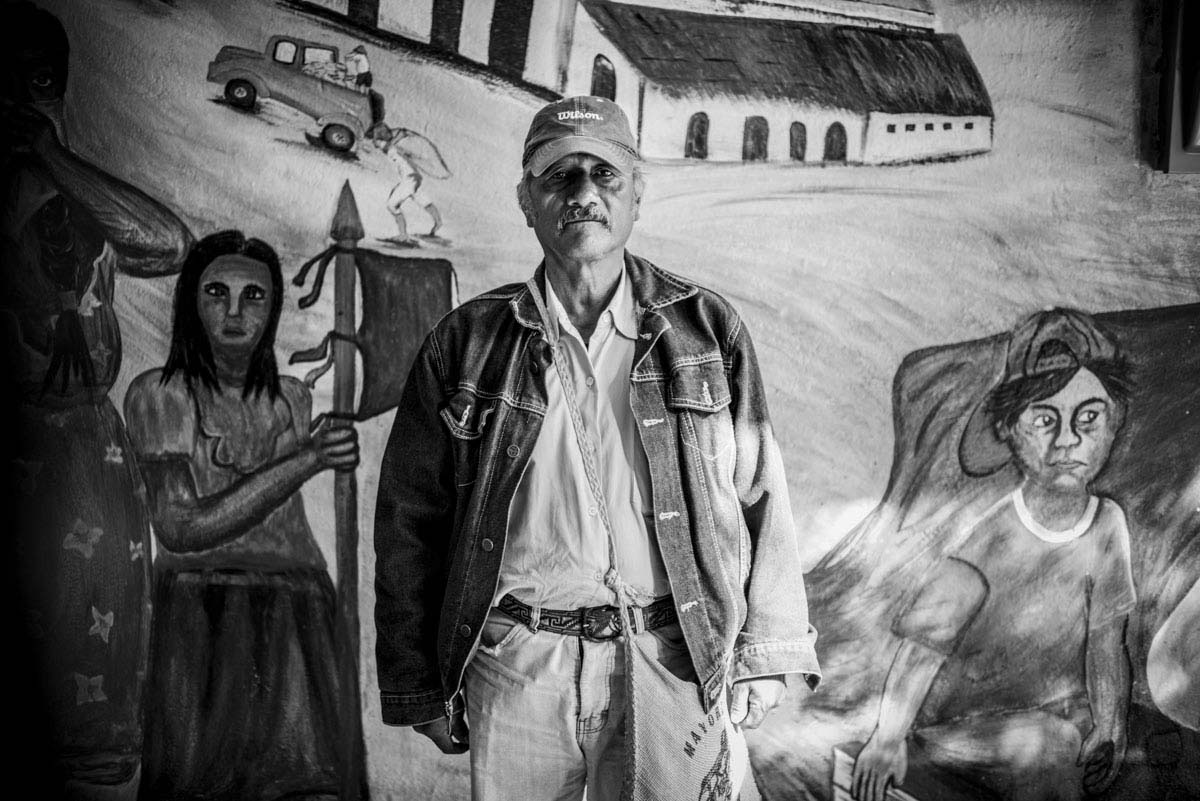

The new report documents signs of torture on at least 17 of the more than 100 suspects who have been arrested over the student disappearances, among them police officers and alleged cartel gunmen. While the suspects could have been involved in the crime, the torture allegations raise doubts about their testimonies. “We never defend criminals, but we also know that thanks to torture, they say what is convenient for the attorney general’s office,” Mario Gonzalez, the father of one of the missing students, said Monday following the release of the report. (The issue of torture in Mexico has been in the news following the emergence of a recent video that showed soldiers and police suffocating a suspected kidnapper with a plastic bag, prompting the nation’s defense secretary to offer a public apology.)

The report also examines the mishandling of crime scenes in the Iguala investigation. Key sites, such as the garbage dump where students were supposed to have been burned, were left unguarded. A charred bone fragment, identified though DNA to be one of the students, was found in a bag in a river near to the dump. However, the experts raise questions about the shady presence of federal officers by the river in the days before this bag was found. The parents of the disappeared students said Monday that there should be an investigation into whether evidence was moved or planted.

President Peña Nieto responded to the report with a tweet promising to take the experts’ findings into account. “The PGR_MX (Attorney General’s Office) will analyze the complete report to enrich its investigation into the tragic events of September 26 and 27, 2014,” he said Sunday. However, Mexico’s government has already said it would not renew the contracts of the experts after April.

Police have long worked with drug cartels across Mexico, exacerbating bloodshed that claims thousands of lives every year. The webs of corruption have hampered criminal cases, and the role of experts raised hopes that there could be a more open investigation into the Iguala attacks. However, Carlos Beristain, one of the experts, said Monday there is still much work to be done. “We are leaving with a bittersweet taste,” Beristain said. “The case is not closed.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com