Erik Kessels lives a fairly unorthodox life. The founder of the 25-year-old advertising firm KesselsKramer, he works alongside 30 other creatives in a repurposed church in Amsterdam with a built-in playground near his desk. Instead of elevator music, a caller put on hold is prompted, “For frivolity, press 6. For the not-quite-chief executive officer but one day you never know, press 8,” or “for a mildly unpleasant electric shock, press 92.” His work philosophy is simple: creativity is spawned by happy accidents.

“Today, everything points towards perfection,” he says. “Computer programs autocorrect misspelled words, phones photograph the light as light and the dark as dark and applications set straight even the slightest misalignment. There are no surprises on the journey, there’s no leverage for a chance misadventure.”

It’s the premise of his latest book, Failed It!, a pocket-size manual for successfully screwing up.

In the process of creative thinking, it’s good to sometimes do a little bit of a wrong thinking, Kessels says. “You might even deliberately point yourself in the wrong direction or make what at first glance seems a mistake to stumble upon a new idea that would not have been considered in a perfect world.”

Kessels in interested in how the mistakes of an amateur photographer can be inspiration for thinking differently about how to approach a subject. “The whole discipline has become very democratic,” he says. “Everybody is a photographer and people that are not directly professionals and not even gifted with a certain talent can make an unexpectedly beautiful picture.”

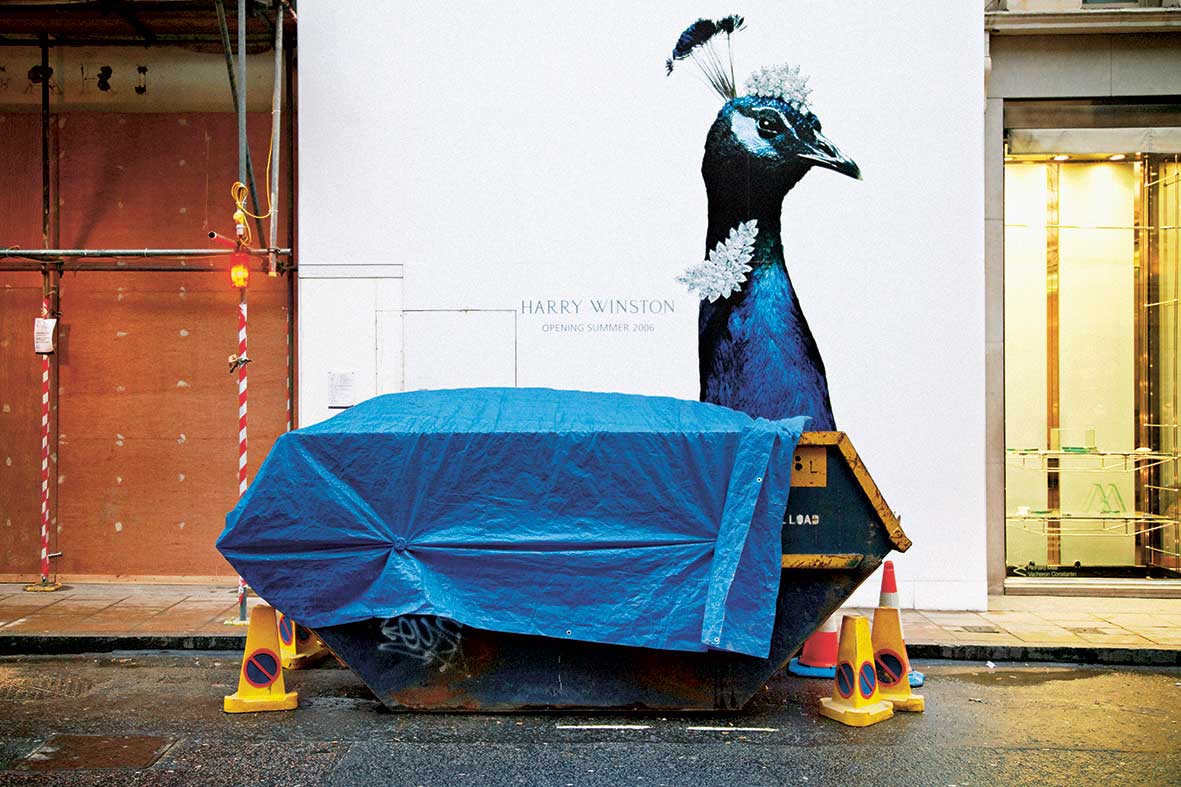

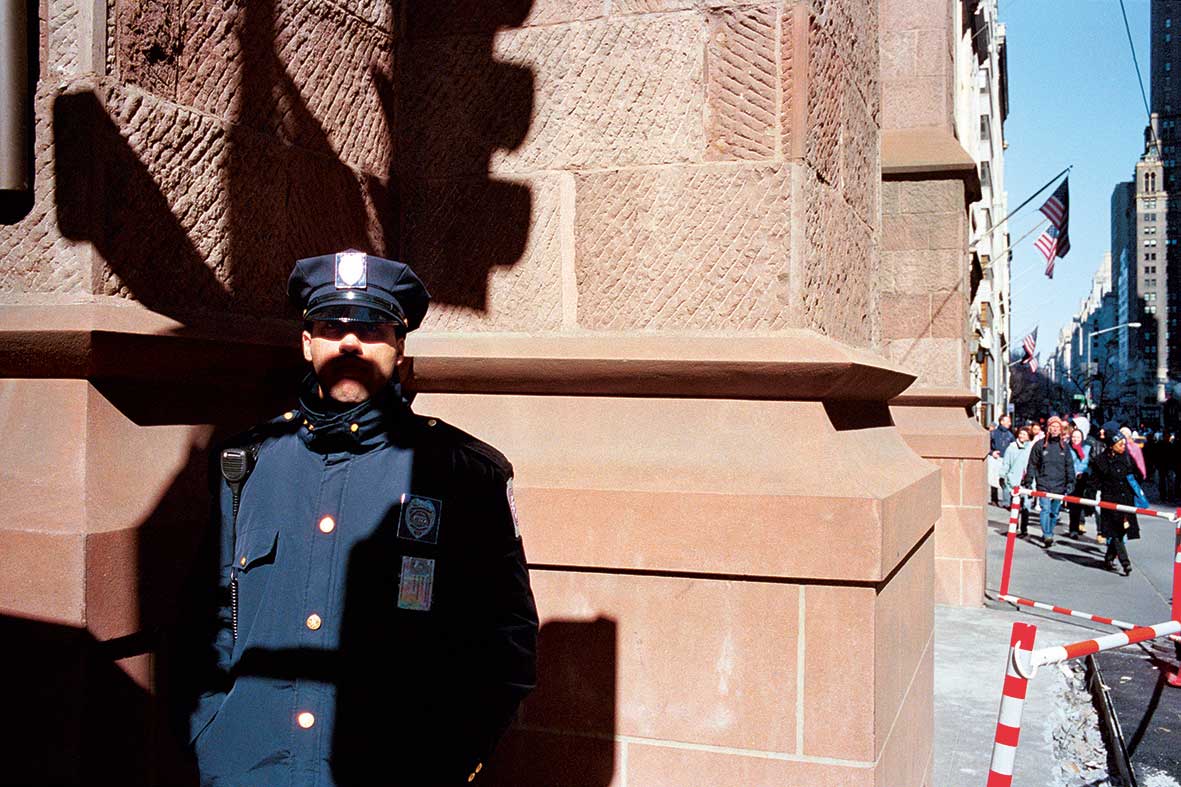

The book, an interplay of image and text, offers a look outside of the box: a model leans into her own legs on a misplaced billboard; a shadow mimics a mustache on a police officer on Fifth Avenue; an orange blob covers the subject’s face in an accidental finger misplacement. One chapter features a dozen images taken by a family fighting against one of the greatest mysteries in photography: how to shoot your black dog. The black blob with phantom-like, over-exposed eyes lurks almost perniciously in the background of each photo. In another section, puzzles are mixed in an unexpected collage of subjects. In another, the tail of a bird wiggles across a public webcam.

They are examples Kessels likes to surround himself with as inspiration for his own work. Kessels—the first non-photographer to be nominated for the Deutsche Börse prize for a photo essay that used his father’s unfinished restoration project of an old Fiat 500 as a parallel to a life come undone—does not consider himself a photographer but an image collector or reappropriator.

He began his career in illustration, which led him to advertising. He worked for eight years in different agencies across the Netherlands and England before he decided to open his own advertising firm. He grew restless.

“To be honest, I hate advertising,” he says. “Most of the stuff is very middle of the road and only there to comfort people and companies. It treats consumers like stupid imbeciles and fails to open up the dialogue.”

In 1996, he joined with Johan Kramer to build an advertising firm that upheld the values they wanted to work by—that includes trial and error. “For 20 years now, we have not let anything leave the door that we didn’t want to see back again,” he says. “Much of that came through experimentation and going beyond the status quo.”

Erik Kessels is the Kessels in KesselsKramer, an independent communications agency in Amsterdam.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com