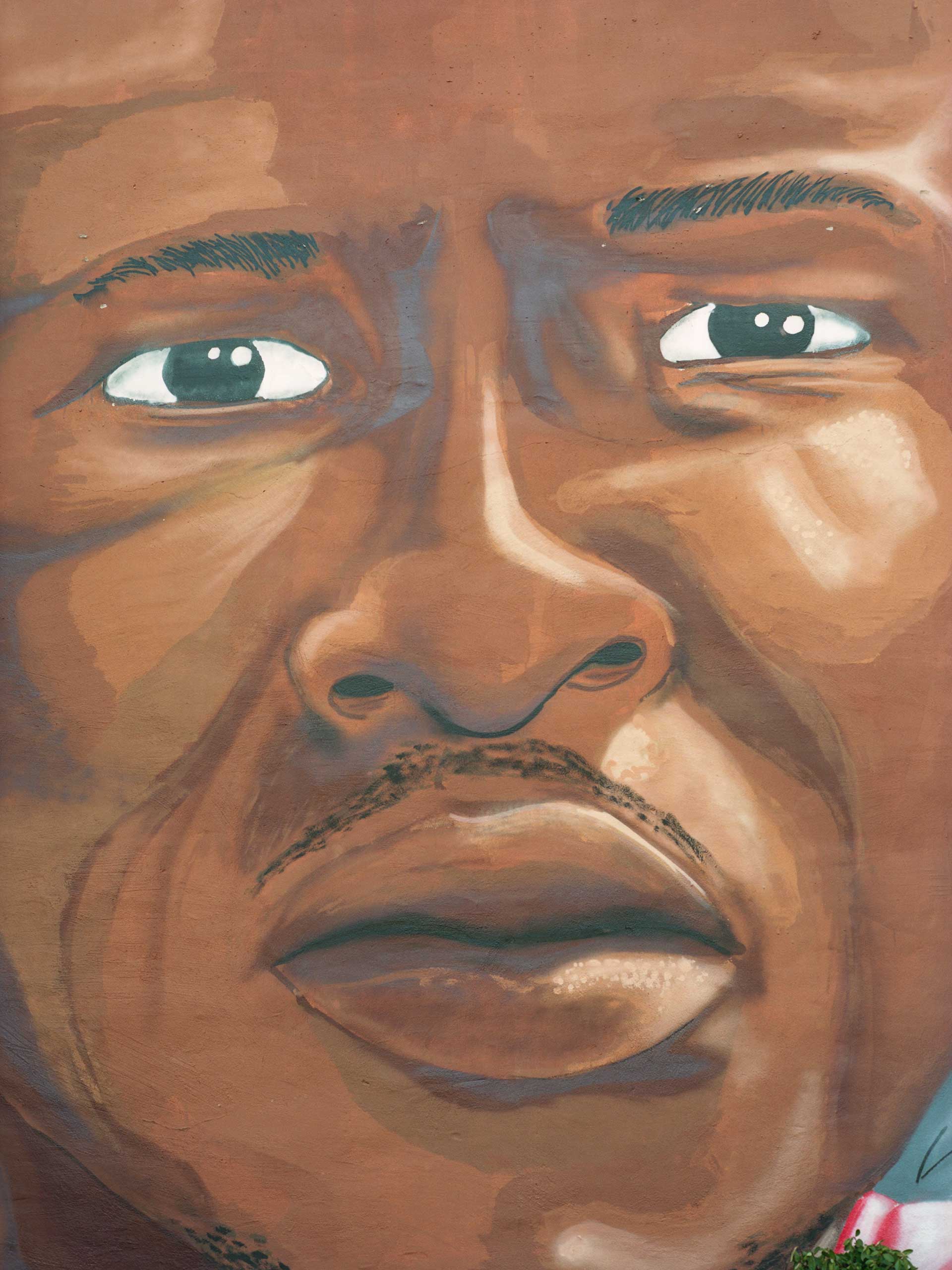

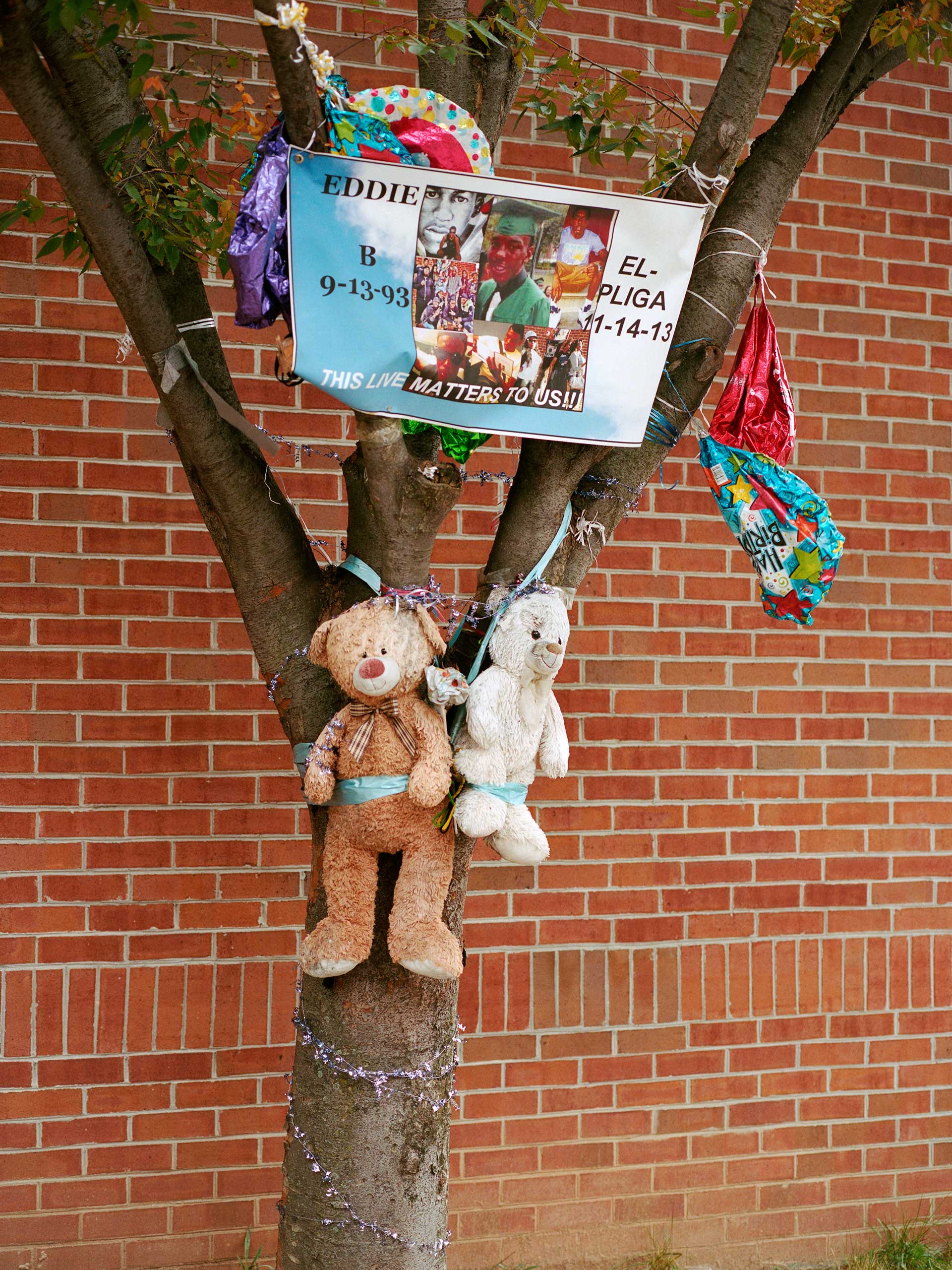

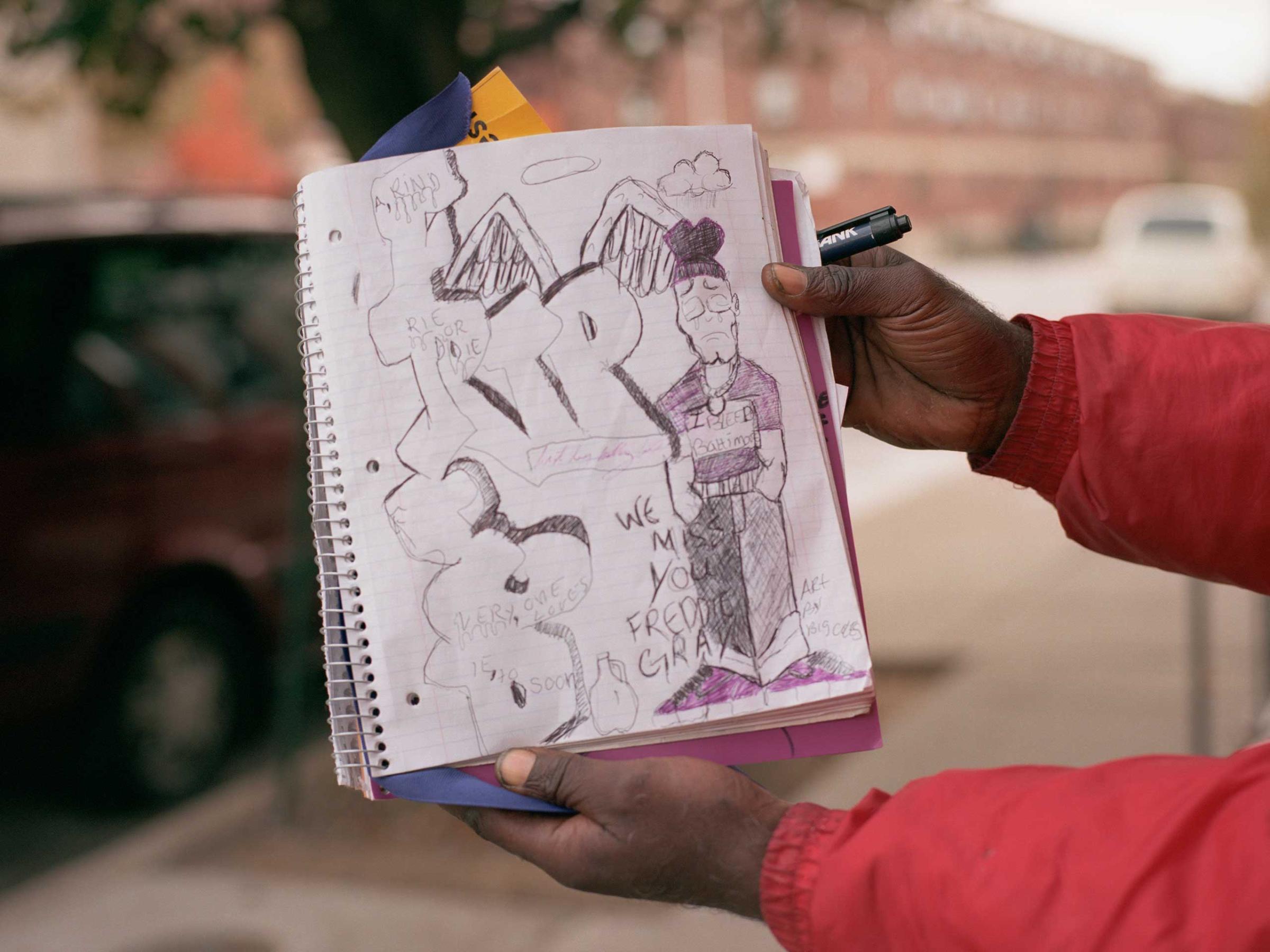

From his fourth-floor window, Baltimore Police Commissioner Kevin Davis can see both the city’s humming downtown and its scarred west side, where a series of events set off by a black man’s death in police custody just over one year ago led, among many other things, to Davis sitting in this office right now. It was there in West Baltimore on April 12, 2015, that Freddie Gray was arrested and placed into a police van before dying under still-murky circumstances a week later, where police clashed with students at a mall following Gray’s funeral, where protests erupted into riots that played in a seemingly endless loop on cable news.

Davis was then in his third month as Baltimore’s deputy police commissioner, and he remembers seeing images of the early unrest from command headquarters here and thinking: Our officers are not equipped for this.

He was right. Gray’s death exposed the long-simmering mistrust between the city’s cops and the African-American communities they’re sworn to protect. The resulting protests—and the national attention they attracted—laid bare the systemic inequalities between poor, majority-black neighborhoods like Sandtown-Winchester, where Gray lived his entire brief life, and the city’s growing, majority-white neighborhoods surrounding the Inner Harbor. The anemic response to the unrest had another consequence: Davis being named police commissioner after his predecessor Anthony Batts, who was widely criticized for his handling of the violence, was fired July 8.

All of which means Davis, 47, has one of the most difficult jobs in American policing. He oversees a department distrusted by many citizens—six officers face criminal charges in Gray’s death while others are scrutinized anytime they make an arrest—and criticized for both over-policing and de-policing, all while trying to lower historic levels of crime and boost officer morale.

“The city and the police department had post-traumatic stress disorder” after the riots, Davis says. “And that trauma exists to this day.”

Read more: What’s Behind Baltimore’s Record-Setting Rise in Homicides

Over the last few months, Davis has worked to reshape both the department and the way it polices the city’s most violent communities. BPD now partners with federal agencies to focus on hundreds of suspects it believes are responsible for most of the city’s crime. He’s increased arrests overall, which plummeted last summer as violence spiraled out of control. And he’s tried to repair relationships with minority communities, something residents and community leaders say remains far from healed. Just this week, meanwhile, one of his officers shot a teenager carrying a fake gun and a local TV station was evacuated after a bomb threat. And on April 27, Maryland State Senator Catherine Pugh won the Democratic nomination for mayor after the once-popular incumbent, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, chose not to run for re-election. In this heavily Democratic city, Pugh is all but certain to be the next mayor. She has been complementary of Davis and said this week she wants to keep him on as commissioner.

Looming over it all are the criminal trials of the six officers charged in Gray’s death. The indictments were credited by many protesters with helping temper the unrest last year, but the cases have stalled after the first ended in a hung jury. Amid this uncertainty, Davis’s promises of a more understanding police force have been met with wariness by some.

“It’s a delicate tightrope,” says Jamal Bryant, pastor of Baltimore’s Empowerment Temple and a civil rights activist. “It’s like dating an abuser who says I’m never going to do that again. Everyone’s walking on eggshells. Will there be a provocation? Has it really changed?”

Searching for Answers in Baltimore a Year After Freddie Gray’s Death

Davis had dealt with a reeling police department before. In 2013 he was named police chief of Anne Arundel County in suburban Maryland after one previous chief resigned over accusations he gathered information on political opponents and another stepped down after making homophobic slurs. Before that, Davis served with Prince George’s County, another suburb in Maryland, for more than two decades, where he often oversaw the police’s response to small-scale unrest and overly rowdy college students in College Park. But what he saw and felt on April 25 last year was different.

That day, a brief skirmish involving police took place outside Camden Yards, home of the Baltimore Orioles, in the city’s downtown tourist district. People threw water bottles at officers; police cruisers were damaged. Later, protesters threw rocks at police. Photographers covering the protests were roughed up. By the end of the night, six officers were injured and three dozen people had been arrested.

“That night at the Western [district], I really got a sense that there was some significant raw energy, emotions, anger that we weren’t going to see the last of,” Davis says.

That night proved to be a precursor. On April 27, after Gray’s funeral, a confrontation between police and a group of high school students outside the Mondawmin Mall touched off days of sometimes violent riots. A CVS pharmacy in West Baltimore was looted and then torched, becoming the physical emblem of the city’s eruption. Drugs were stolen from two dozen other pharmacies, according to Baltimore police and the Drug Enforcement Agency. An apartment complex for seniors that was under construction was set on fire. For older residents, the riots were an echo of what occurred in 1968 after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Six people died and 700 were injured then, and the worst-hit neighborhoods still bare the scars of the unrest.

Read more: Baltimore Sees Worst Month for Homicides in 40 Years

Before Gray’s death, crime had largely stabilized. The number of homicides hit 197 in 2011 and remained in the low 200s each year after that, an improvement from the much more violent early 1990s. But in the weeks and months after Gray’s death, violence spiraled out of control. Shootings increased by 140% between April 20 and July 12 compared with the year before. Homicides increased by 92%, and July—with 45 homicides—became the city’s deadliest month on record.

The crime spike coincided with a drastic decrease in arrests. During the period, arrests went down by 30%, including those for murder, attempted murder, burglary, and larceny. And the opposing directions that crime and policing took during that period have been enough for criminologists to re-litigate a common debate within the field: Does policing actually lower crime? It would seem intuitive that it does. You put more cops on the streets, crime goes down. Fewer cops, more crime. But that link has never actually been proven.

“For a long time, criminologists have tried to find a relationship between arrest patterns and crime, and it’s always been pretty weak,” says Stephen Morgan, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “It’s frequently interpreted that policing behavior and tactics ultimately don’t move the crime rate all that much. But we’re in a period where there’s some important new data.”

Morgan studied the relationship in Baltimore and dubbed what occurred last summer as the “Gray effect,” which he describes as cops unwilling to proactively arrest suspects following the indictments in Gray’s death. Peter Moskos, a John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor and former Baltimore police officer, sees a similar link.

“There was less proactive policing, criminals were not being confronted by police routinely, and violence and murders went up,” Moskos says, adding that he believes the charges against the six officers led to a “chilling effect.”

“Cops basically said, ‘Why should I clear a drug corner when that could happen to me?’” Moskos says.

Some criminologists, however, believe the spike in crime is due more to the looting of about 30 pharmacies throughout Baltimore, which police say allowed for an estimated 288,000 prescription drugs to flood a market with a history of violent drug wars.

Read more: Baltimore Police Union Chief Says Criminals ‘Empowered’ By Riots

“A considerable portion of homicides is connected to the drug trade,” says Jeffrey Ian Ross, a University of Baltimore criminologist. “That’s where you have to look. There were new players in the market, and the balance of power can change and lead to increased homicide because people are juggling for power.”

Davis, too, points to the looting of pharmacies as a key reason the crime rate rose, saying the abundance of supply led to violence over the possession of prescription drugs and the street corners needed to sell them. As far as de-policing is concerned, Davis says there was “never a discussion to reduce proactivity” but that many officers saw the indictments over Gray’s death “and they couldn’t rectify that in their mind.”

Since taking over, Davis has made moves aimed at reform both big and small. He’s allowed officers with visible tattoos to wear short-sleeves in the summer. He started an internal police newsletter highlighting members of the rank-and-file. He restored patrol posts, which require officers to walk specific sections of a neighborhood, and did away with patrol sectors, which clumped officers together. He says surprise inspections of prison transport wagons have shown 100% compliance for putting prisoners in seat belts, a policy instituted after it was shown that officers had not placed Gray in one.

“For too long we had a standard operating policy and then we had a standard operating practice, and they were too far apart,” Davis says, acknowledging that that sometimes included so-called “rough rides” where a suspect was deliberately thrown about.

Davis is also heading up a war room involving five federal agencies—the FBI, U.S. Marshals Service, ATF, DEA, and the Secret Service—to focus on more than 600 “trigger pullers” who Davis describes as violent, repeat offenders responsible for a majority of the crimes in the city. Since last year, 47 of them have been murdered.

“As tragic as that is, that convinces us beyond any other statistic associated with the trigger pullers list that these are the right, vulnerable people,” Davis says.

Davis’s efforts, however, have critics within the ranks. Gene Ryan, a Baltimore Police Department lieutenant and president of the Baltimore City police union, says that following a “honeymoon period” after Davis was named commissioner, some of the rank-and-file feel Davis has spent more time on public perception and less on their needs.

“Our members are unhappy because it appears the commissioner is taking more time to keep his job than appeasing dissatisfied officers,” Ryan says. “They would prefer he be out in the field with them instead of doing certain functions. There has to be a balance in dealing with the community.”

Ryan describes the department as overworked, underpaid, and struggling to attract enough qualified officers to keep up with those who are retiring or leaving for better-paying jobs in surrounding counties. He says the police department lost 251 officers last year who either retired, took another job, or were fired, while only hiring 91 to replace them. In 2011, the department lost 203 but hired 202.

“I’ve been here 33 years, and I have to say this is the worst morale I’ve ever seen in my career,” Ryan says.

While morale may still be low, Davis has been able to get officers to make arrests again, which by the end of the year were up 20% from their post-Gray low. And while there have already been more than 70 homicides this year, it appears the murder rate won’t reach the levels it did last year. The long-term question, however, is whether Davis can help repair the force’s relationship in neighborhoods like Sandtown.

“There’s still a long way to go,” says Harold Carter, Jr., the pastor at West Baltimore’s New Shiloh Baptist Church. “But it seems to be at a point where it can now start to turn the corner.”

Many residents, however, get the sense that not much has changed since last year. “It’s gotten back to normal, but the people who didn’t trust the police before feel the same way now,” says Bamba Kane, 43, a West Baltimore resident.

Looking out over West Baltimore, Davis says he believes the relationships there are stronger than they were this time last year. He acknowledges there’s still much to do, but he’s confident of at least one thing.

“The police department, the community, nobody wants to see a repeat of last April,” Davis says. “I’m convinced we’re not going to see it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com