Correction appended: April 25, 2016.

Retired Marine general James “Mad Dog” Mattis, who hung up his uniform three years ago, batted away speculation about running for President on Friday—but didn’t rule it out. Mattis—call sign “Chaos”—was fielding questions from the audience at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington following a talk on Iran, but the first query had nothing to do with Tehran.

Instead, a reporter wanted to know if the former head of U.S. Central Command (2010-2013) has given any thoughts to running for the White House, as many of his supporters are arguing he should. “No, I haven’t given any thought to it,” he responded quickly. Well, what about the rumors that he might run? “I think people like you know that better than I do,” he said, before moving on quickly to the friendlier terrain of international relations. After the gathering, the 65-year-old Mattis, also known as the “Warrior Monk” for his ascetic intellect, declined to issue a flat denial that he would run.

His coyness is atypical. During his 44 years in uniform, part of his attraction was his willingness to offer his unvarnished, and sometimes, impolitic, opinions. “You go into Afghanistan, you got guys who slap women around for five years because they didn’t wear a veil. You know, guys like that ain’t got no manhood left anyway,” Mattis said in 2005. “So it’s a hell of a lot of fun to shoot them.”

What is it about military leaders that has led so many voters to champion them for the Presidency? After all, it’s not like the nation has emerged victorious from its recent wars. But it actually may have more to do with the personal qualities Americans sense in their military leaders, rather than the battles they were ordered to fight.

“As the polls show, Americans overwhelming pick the military as the institution in U.S. society in which they have the most confidence, so it isn’t surprising that some may look to the leaders of that institution to lead the nation as a whole,” says Charles Dunlap, a retired Air Force major general who now heads the Center on Law, Ethics and National Security at Duke Law School. They also perceive military officers as largely altruistic and honest, “qualities that many Americans find conspicuously absent from the traditional politicians that they see these days.”

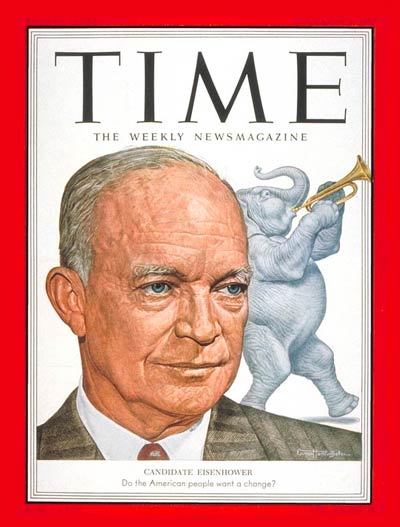

It’s a long tradition. George Washington was the first general who went on to serve as President of the United States, and some voters continue to think it’s good training for the job. There was former Army general William Tecumseh Sherman in 1884, whose emphatic “no thanks” (“I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected”) has been codified in the nation’s political lexicon as a “Shermanesque statement.” Some championed ex-Army general Douglas MacArthur in 1952, but he demurred (another retired Army general, Dwight Eisenhower, ultimately won that election, the last of 12 generals to do so).

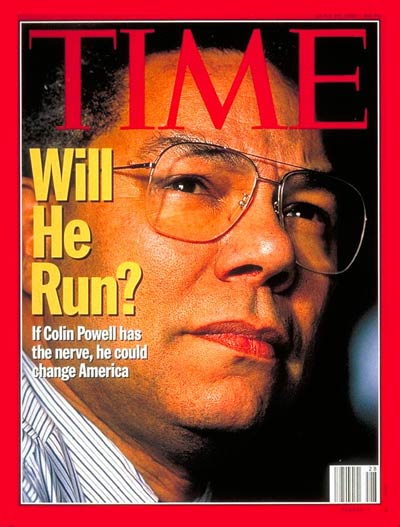

Military victory is a powerful political tonic: just ask Colin Powell, who oversaw 1991’s Persian Gulf War from the safety of the Pentagon and was white-hot as a GOP contender in 1996. But Powell ultimately concluded he didn’t have the passion a presidential campaign required and bowed out (although he still won the New Hampshire primary afterward, as a write-in candidate). A second Army four-star, Wesley Clark, tried but failed to win the Democratic nomination in 2004.

“The transition from general to President is a difficult one, but it is not the hardest part of the assignment,” says Peter Feaver, a civil-military relations scholar who has served on the National Security Council staff in both Democratic and Republican White House. “The really hard part is the transition from general to candidate.”

Despite that lack of battlefield success since 9/11, the names of senior military officers who served or oversaw the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq continue to be mentioned as Presidential contenders. Beyond Mattis, they have included retired Army general Stanley McChrystal, retired Navy admiral Mike Mullen, and retired Army general David Petraeus.

The public—especially those who’d like to see a military veteran in the White House—tends to view retired officers as Republicans, even if they haven’t declared a party affiliation. “What we have here is further evidence of the desperation engulfing the right-wing Establishment as it contemplates the prospect of (GOP candidates Donald) Trump or (Ted) Cruz winning the Republican nomination, and therefore handing the presidency to the Democrats,” says Andrew Bacevich, a retired Army colonel and military historian.

None of the major candidates still in the running to become commander-in-chief ever served in the military. But they’re aware of the patina that accompanies such service. In a book published last year, Trump said he “always felt that I was in the military” because he attended a military boarding school and “dealt with those people.” Democrat frontrunner Hillary Clinton raised eyebrows in New Hampshire last November with her claim that a Marine recruiter turned her away in 1975 when she tried to sign up.

Yet while military officers may have experience on the battlefield, most are unwilling to try to cross the political minefield that American politics has become.

“Today’s political process is so prolonged and so onerous that virtually no senior military leaders of the current generation would seriously consider running,” says former three-star Army general David Barno, who led all U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan from 2003 to 2005, and now lectures on civil-military relations at American University. “The realities of a painfully long two-year presidential campaign, the ugly personal attacks on candidates and their families, and the highly-polarized nature of the party primaries are just a few of the reasons that make even considering the idea unpalatable to nearly anyone retired who once wore stars.”

Correction: The original version of this story misstated Eisenhower’s rank. He was a five-star general.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com