If you wanted to buy a Sam Cooke album, where would you go?

If you know the answer to that question, you’ve probably seen Prince’s glittering and hugely underappreciated directorial debut, one of only three features he directed in his all-too-short filmmaking career. In the 1986 Under the Cherry Moon, an ode to Hollywood glamour shot in plush, feathery black-and-white, Prince himself appeared as a pianist and hustler who falls for snooty rich girl Kristen Scott Thomas. At first, she’ll have nothing to do with him, and Prince, wounded, decides to get the better of her. At a fancy dinner, he writes the words “wrecka stow” on a napkin and asks her to read them aloud. She does, repeatedly, in her posh, plummy accent. (It doesn’t hurt that she’s wearing an elaborate beaded flapper headdress.) In her white-girl cluelessness, she’s sure it’s a nonsense phrase, and the more she says it, the funnier it gets. Prince and his scamming partner, played by Jerome Benton, destroy themselves laughing. It’s a moment of naughty joy, a triumph of knowledge over education, of taste over breeding, of style over affectation—but, good-natured at its heart, it’s also a moment of unifying anti-snobbery.

In that sense, it’s pure Prince.

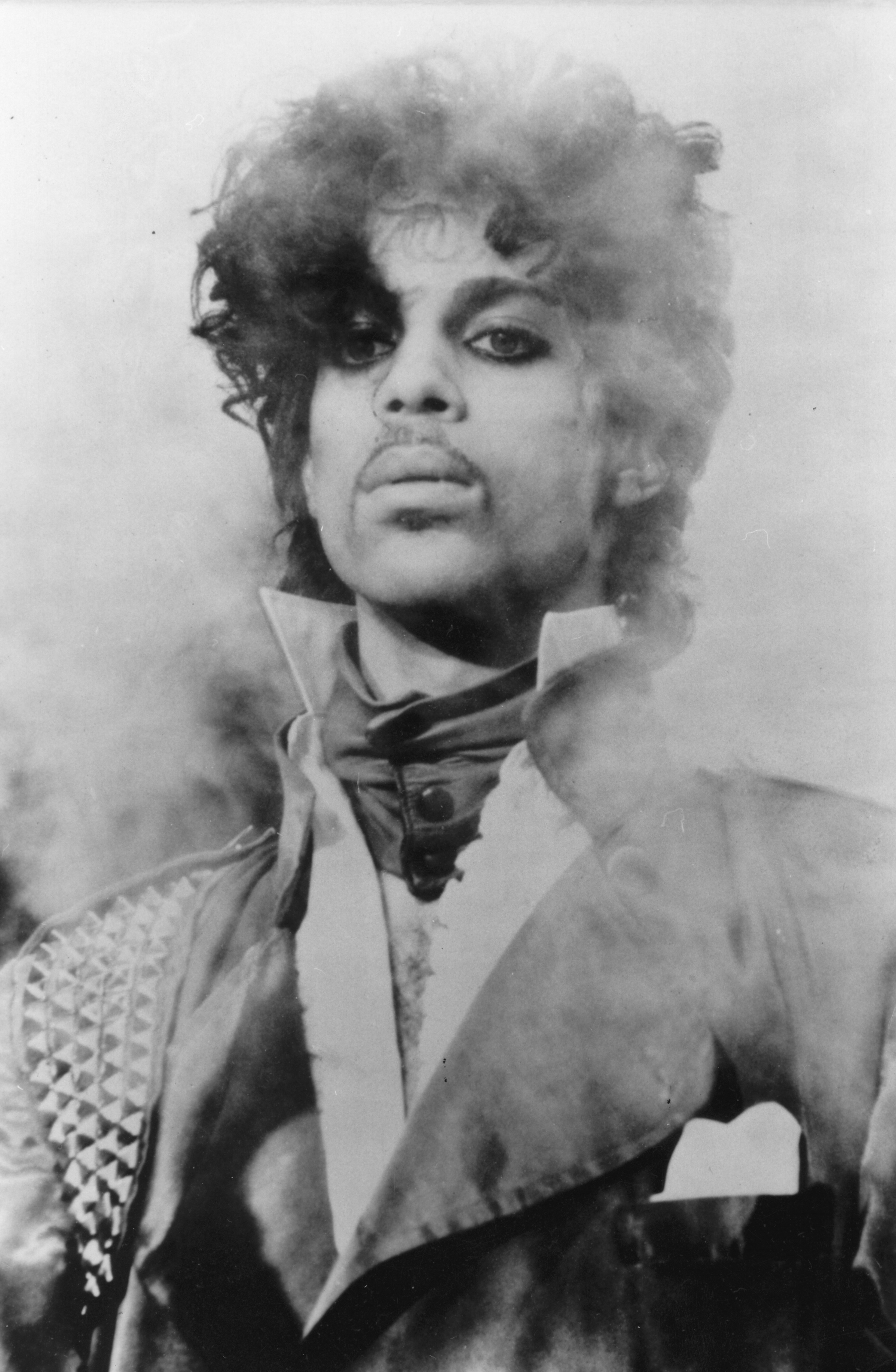

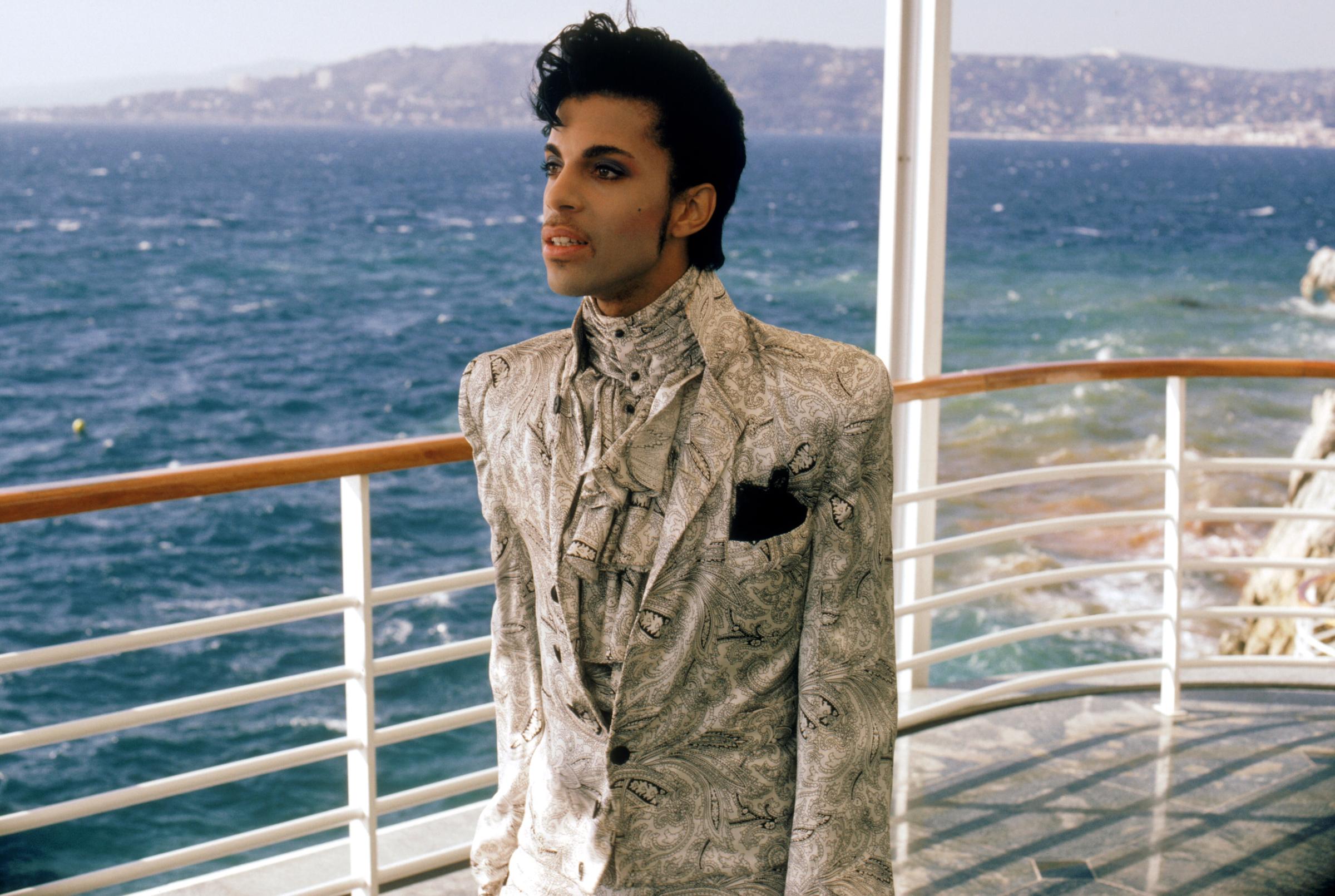

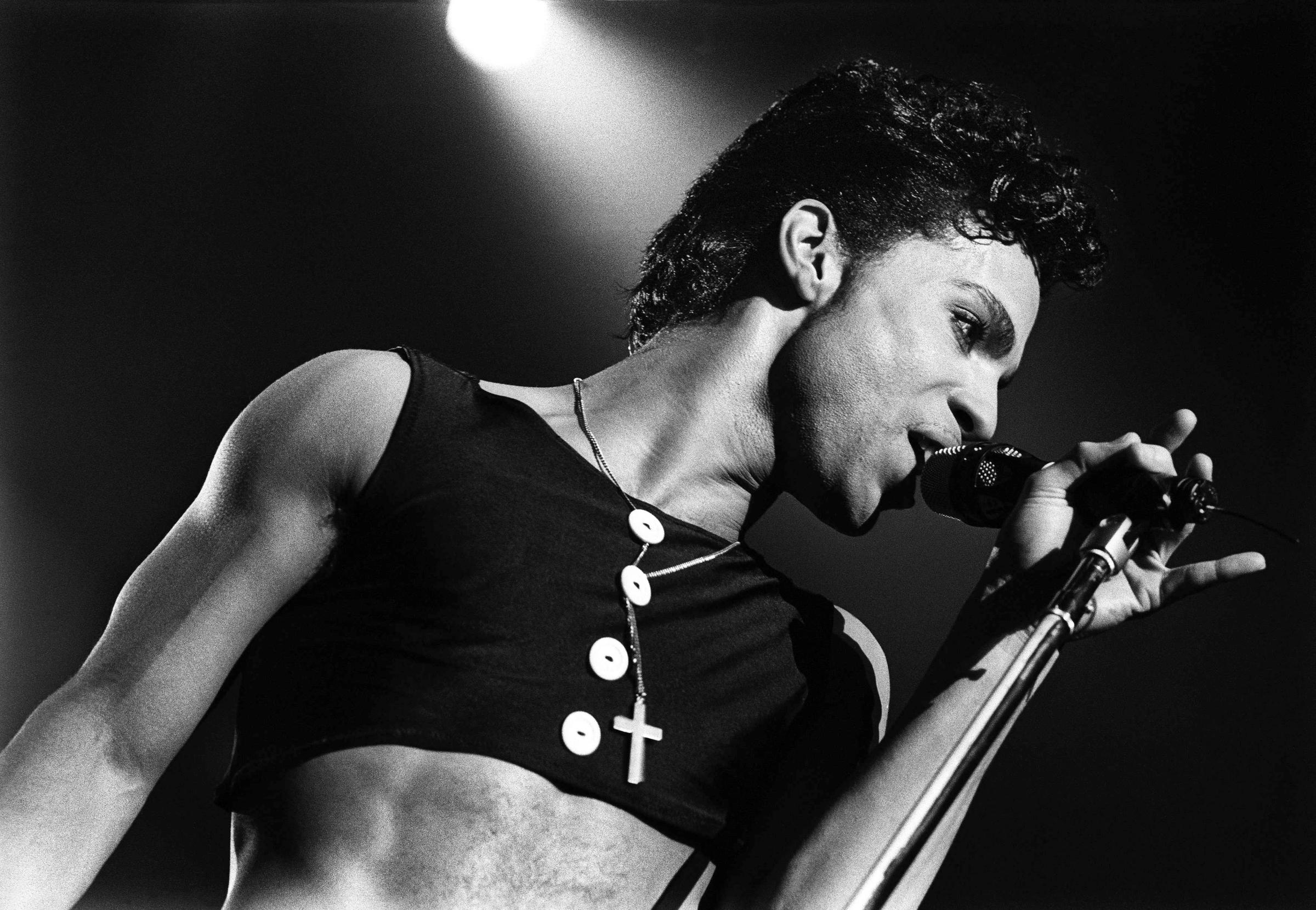

Now that he’s gone, at the unthinkable age of 57, most of us who loved him—is it possible that includes just about everybody?—are desperately wishing we could have kept him longer, for more music, more live shows, more Victoriana-meets-male-go-go-dancer costumes. I want all of those things, too. But I also wish he’d left more movies. Under the Cherry Moon bombed upon its release, but it’s a gorgeous, funny, surreptitiously sophisticated picture, made with a pure and discriminating understanding of what ’30s romantic comedies were all about, including the need—it was much more than a desire—for lush, escapist fantasies. (In the Reagan ’80s, we needed those too.) The film was shot—beautifully, and by Martin Scorsese regular Michael Ballhaus—in lavish locales in the south of France and in Miami. Its gags were fleet and fluffy, rolling by like Rolls Royce-shaped clouds in the sky. It closed with a knockout musical number (“Mountains”), in which Prince, backed by The Revolution, appeared to be floating on a magic carpet in some imaginary Heaven. His costume consisted of side-button bell-bottoms, a miniaturized, midriff-bearing jacket and a gaucho hat tilted back, jauntily, on his head. He was a singing cowboy, a Fred Astaire, a dazzling spiritual cousin to sexpot Jean Harlow. This was a person who understood movies.

At the time, almost no one got it (then-Village Voice critic J. Hoberman was one of the few exceptions). Maybe now Under the Cherry Moon will get the life it always deserved. Prince directed only two other features, the stylish but messy Graffiti Bridge (1990), and the mad, visionary 1987 concert documentary Sign ‘o’ the Times. But he may be best remembered on film as the Kid in the 1984 dazzler Purple Rain, a stylized biopic rendering of his own life as a pop-music prodigy from a humble background, complete with squabbling parents. In Purple Rain, the Kid is a singer and musician struggling to make it big, thwarted at every turn by his arch-rival (played by the supremely likable Morris Day). He meets a girl he likes, an aspiring performer named Appolonia (Appolonia Kotero). They hit it off. He whisks her away from the city on his purple motorbike; they skim through an autumn wonderland of red and gold trees. She’s beautiful, but he may be more so, and cuter, too: When he smiles, you notice that his teeth are small and adorable, like a little kid’s teeth.

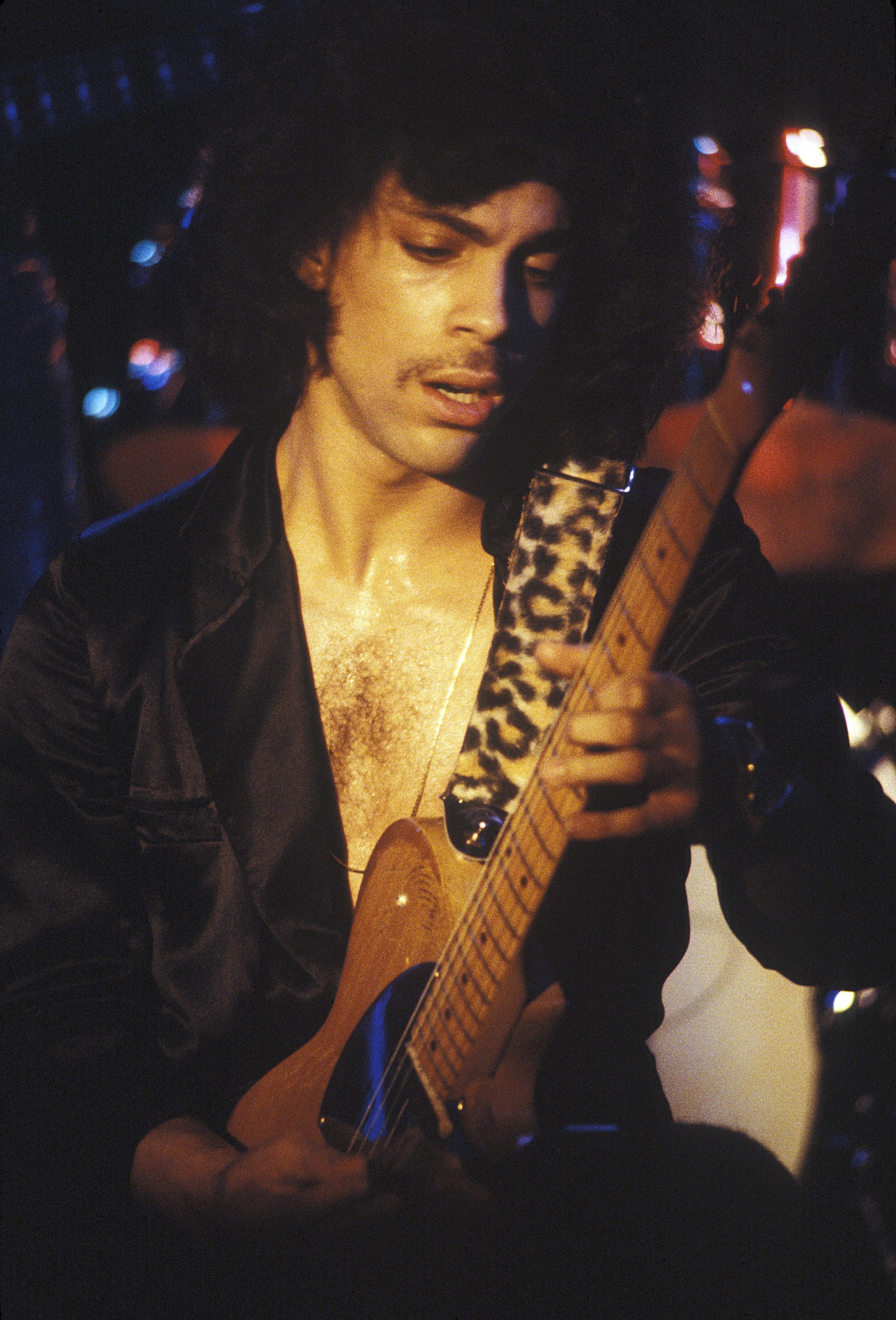

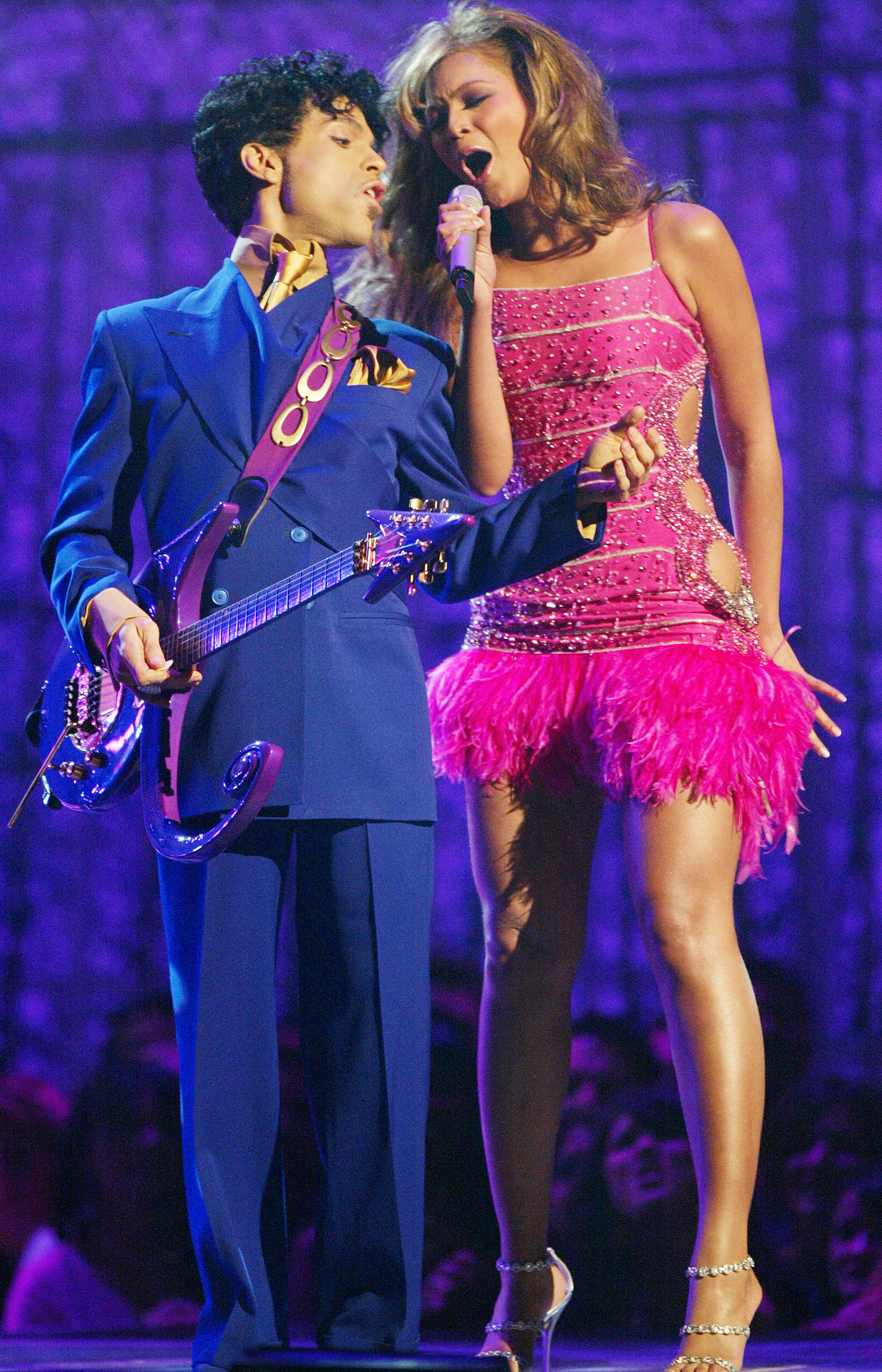

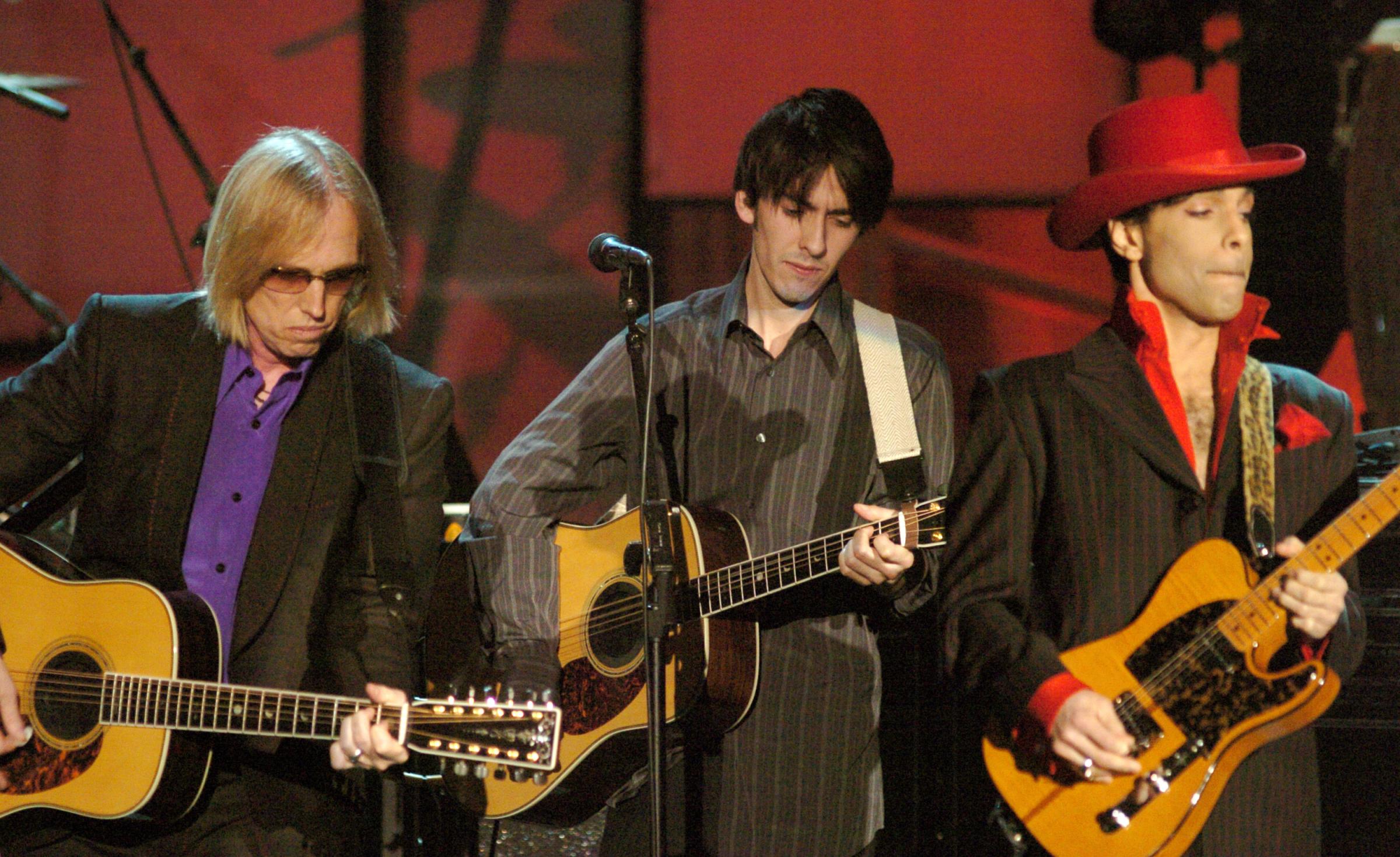

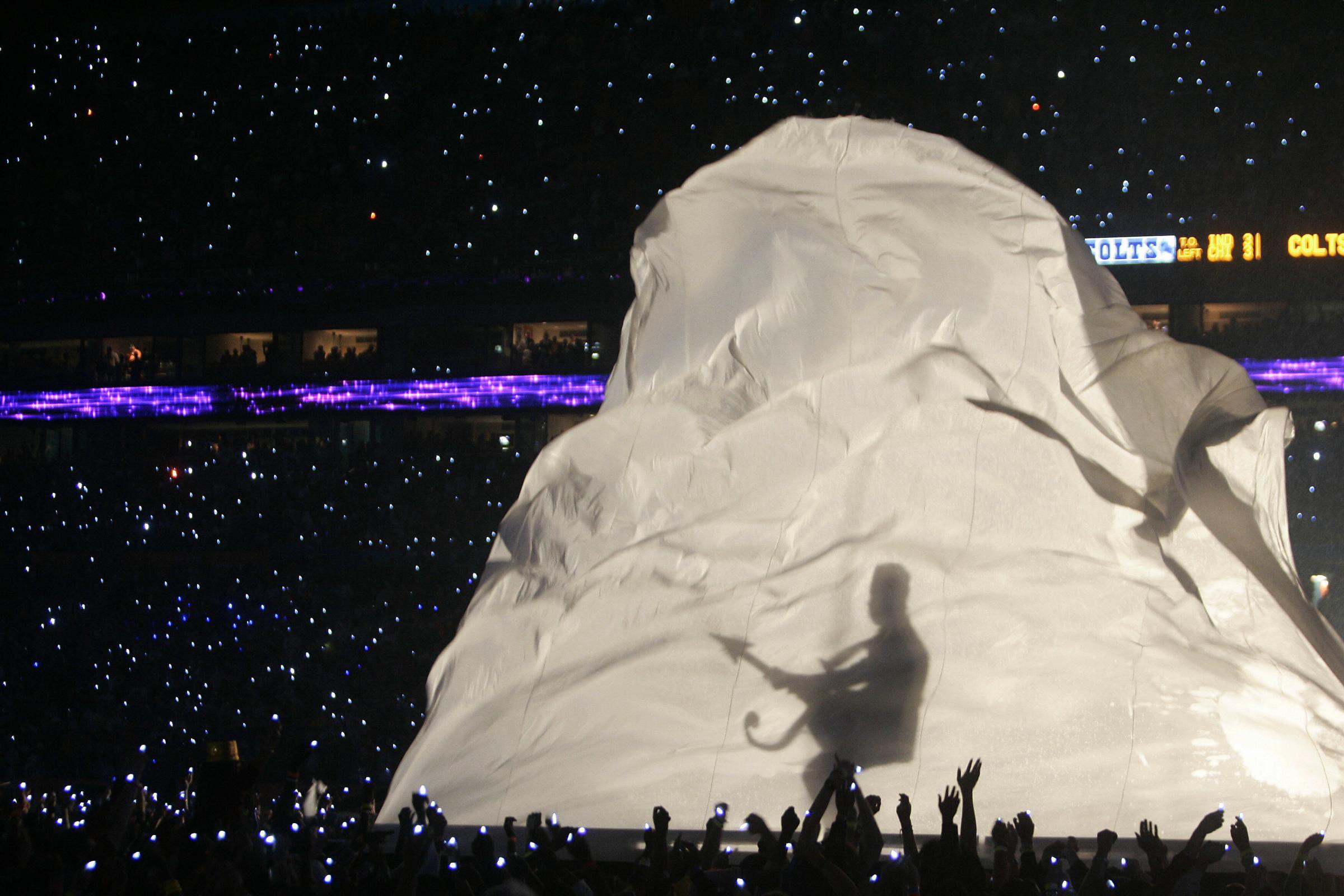

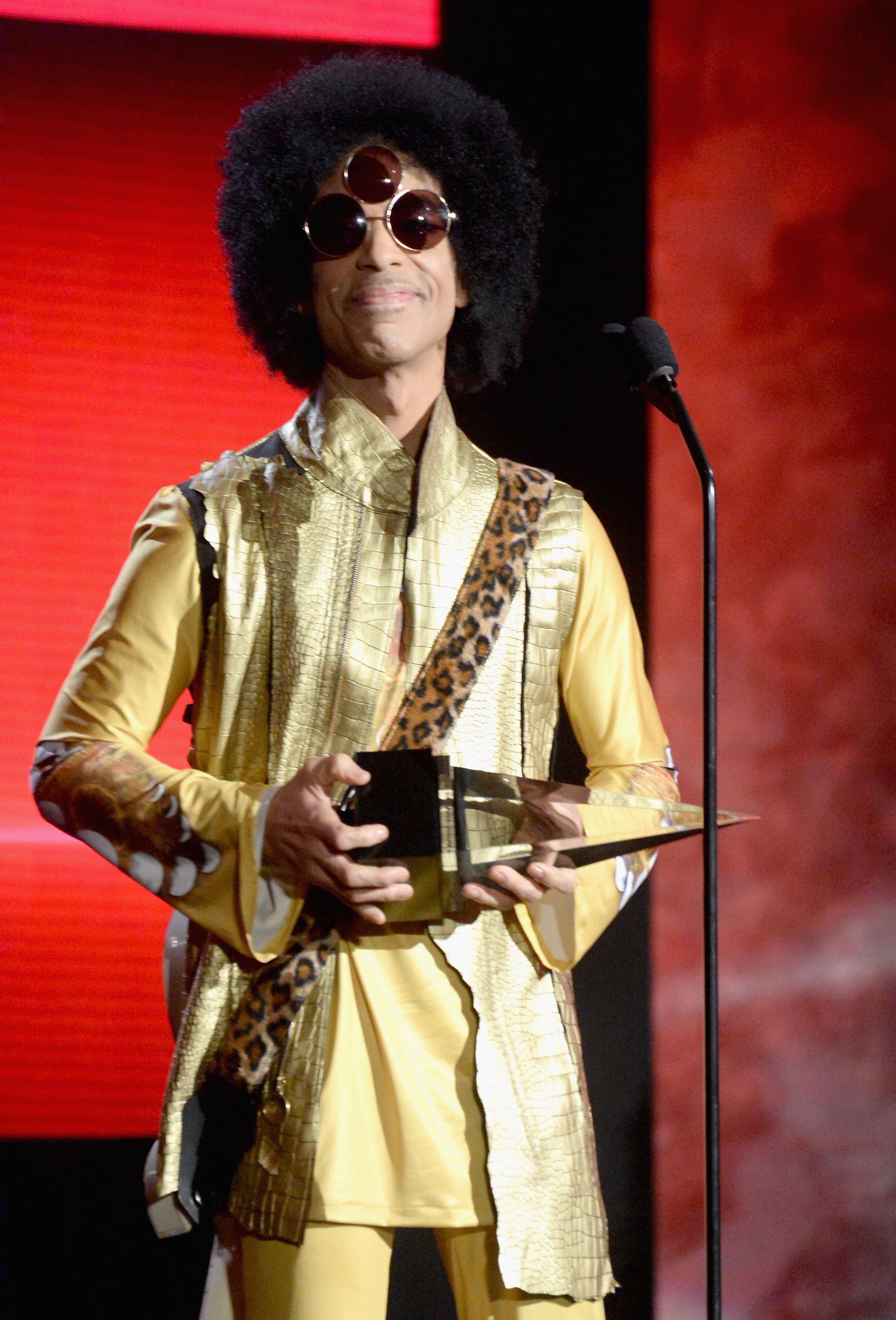

See Prince’s Life in Photos

They make love; he gives her his earring. But her ambition gets in the way, and it hurts him. They fight, violently, and split up. Finally, and thankfully, they come together forever. In between there are songs, lots of them, including the luxuriant ballad “The Beautiful Ones,” which Prince begins (again, with The Revolution flanking him) at the piano, shrouded in purple mist. He’s wooing a girl he’s not yet sure of. He may be confident, but he’s not cocky, at least not now. When he gets to the line “You make me so confused/the beautiful ones, they always seem to lose,” his uncertainty takes the shape of a rippling falsetto run, a flutter of butterflies. He ends the song lying on his back, spent, because this is what love does to you.

One of the certainties of rock’n’roll is that when your beloved idols die, there’s always going to be someone older than you are, telling you how great so-and-so was back in the day, back when people found out about new music by listening to the radio, back when LPs weren’t a novelty item, as they are today, but something you saved for and cherished. Right now—and I apologize in advance—I’m going to be that person. In 1980, when he released his third LP, Dirty Mind, Prince was unlike anything or anyone we had seen or heard before—an heir to Al Green, to Hendrix, to Sly Stone, and yet so far beyond. I stared and stared at that cover: Just look at this fabulous guy, wearing an admiral’s jacket, a neckerchief, and black underpants, challenging the world with his eyes. But there was love in those eyes, too. They were—he was—a seduction from the beginning. I fell, as many, many others have fallen in the years since. The credits of Under the Cherry Moon end with a benediction: “love God may u live life 2 see the dawn.” A dirty mind can also be such a beautiful 1.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com