The criminal charges brought against Michigan officials in Flint’s water crisis this week included several felonies involving tampering with evidence. The evidence in question is a doctored document that made Flint’s lead levels appear allowable under federal guidelines, making water treatment seem unnecessary—and exposing the city’s residents to unsafe drinking water.

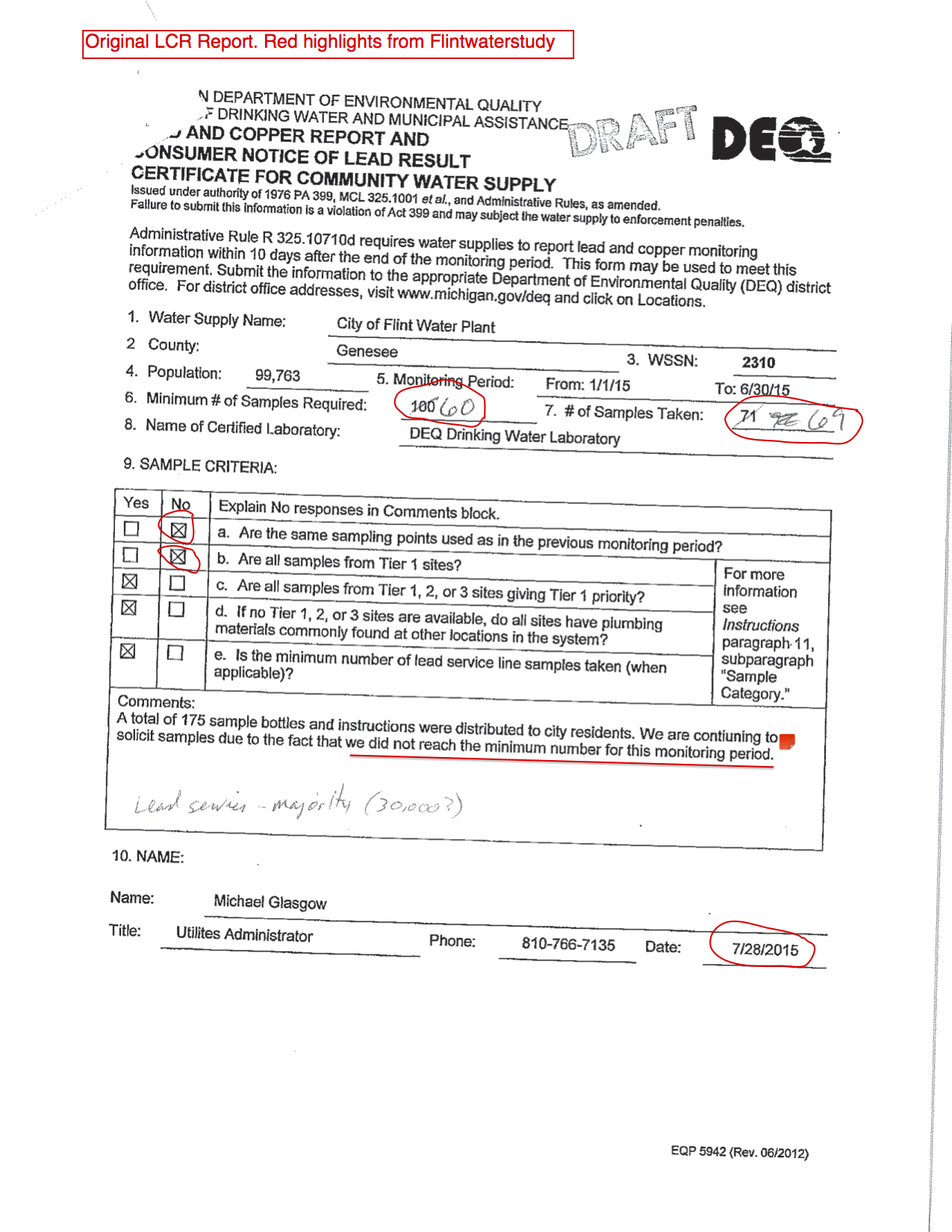

In July 2015, following complaints from residents about the quality of their water, Flint utilities administrator Michael Glasgow filed a lead and copper report to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality showing that the city had collected 71 water samples to test for levels of lead and copper. That was fewer than the MDEQ’s requirement of a minimum of 100 samples needed for an acceptable test.

“We are continuing to solicit samples due to the fact that we did not reach the minimum number for this monitoring period,” Glasgow wrote in the report.

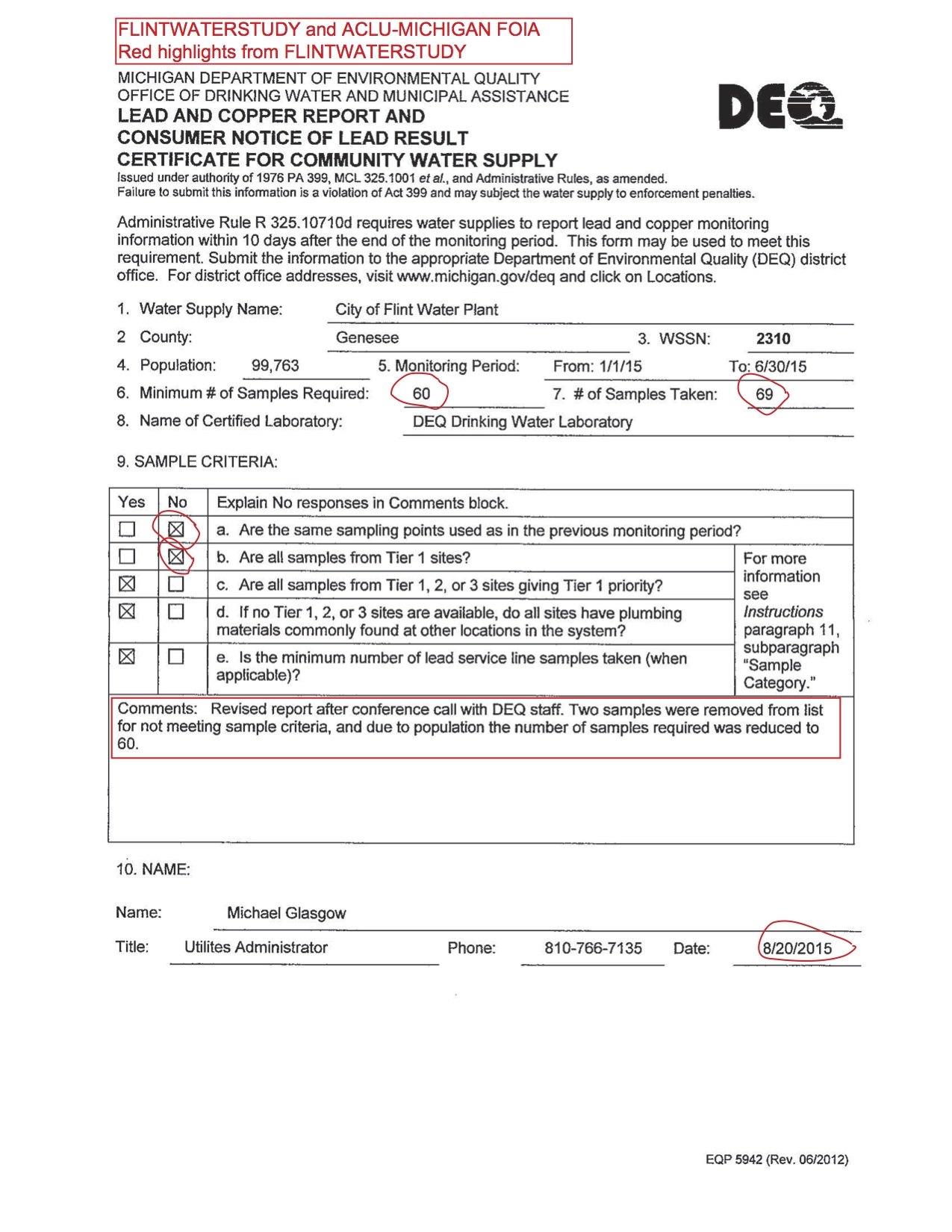

But a month later, Glasgow filed a revised version of the document that was altered. The minimum number of samples required had been changed to 60. The number of samples taken had been changed, too, to 69, and the report notes that those changes occurred following a conference call that included MDEQ staff.

“Two samples were removed from list for not meeting sample criteria, and due to population the number of samples required was reduced to 60,” Glasgow wrote.

(Click here to view a larger version.)

(Click here to view a larger version.)

The two samples dropped were two of the highest recorded by the city of Flint, including a sample from the home of Lee-Anne Walters, the Flint resident and mother who repeatedly questioned officials’ claims that the water was safe to drink. Her home showed lead levels of 104 parts per billion, far above the federal action level of 15 ppb. After learning her sample had been thrown out, Walters says she was told it was because her home had a water filtration system, something that theoretically would have lowered, rather than raised, her home’s lead levels. The second sample that was discarded showed lead levels of 20 ppb, according to an analysis by Michigan Radio, but was tossed because it came from a business rather than a residence.

Read more: The 5 Most Important Flint Water Crisis Emails Released by Michigan’s Governor

Glasgow told Michigan Radio in November that MDEQ officials told him to remove Walters’ sample from the report. On Wednesday, Glasgow was charged with a felony count for tampering with evidence and a misdemeanor count for willful neglect of duty.

Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette also brought felony charges against Stephen Busch and Michael Prysby, both MDEQ employees who prosecutors claim were involved in editing the reports. One of the counts included tampering with evidence, and prosecutors allege Busch and Prysby knowingly and intentionally altered MDEQ’s lead and copper report.

Busch, Prysby and Glasgow or their lawyers have yet to comment publicly on the charges.

Read more: Flint’s Water Crisis Explained in 3 GIFs

The Flint water crisis began in April 2014 when the city switched its water source from Detroit to the Flint River. The city failed to properly treat the water, causing lead to leach into the supply; it took more than a year for officials to acknowledge that the water wasn’t safe to drink. Several investigations are underway, and Schuette suggested Wednesday that more charges would be filed.

Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech civil engineering professor who initially obtained copies of the documents in conjunction with the ACLU of Michigan and released them last fall, says he believes Glasgow was put in an essentially impossible position after feeling pressure from the MDEQ to change the report.

“Mike made mistakes,” Edwards says. “But he’s not in the same league as the bad actors at the MDEQ.”

Edwards says that the report was changed after the ACLU began asking the MDEQ for the documents. He believes altering the documents gave MDEQ’s employees an excuse not to take action.

“If you change the report, it’s less work for you,” Edwards says. “You can get out of doing the job you’re paid to do. If not, they would have had to tell people the water was not safe. They would’ve had to start corrosion control. At some point that becomes criminal.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com