The United States has gone out of its way to support the 1% of Americans who have gone to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq following the 9/11 attacks. But, frankly, a lot of the cheers are simply rhetoric making cracks through which returning troops fall all too often.

Sure, the Department of Veterans Affairs budget has more than doubled, rising from $73 billion in 2006 to a proposed $164 billion next year. But all that spending hasn’t done enough to salve the wars’ unseen wounds, as a nationwide survey of post-9/11 U.S. veterans detailed in Sunday’s Washington Post makes clear.

That becomes even more apparent when you stumble across a report like Unexpected Patient Death in a Substance Abuse Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program, issued Friday by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ inspector general.

An Afghanistan war veteran went to the VA to get help fighting his struggles with drugs and alcohol. That’s why he was in a 24-bed section of Miami, Florida’s VA hospital dedicated to treating addicts.

The Substance Abuse Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program [SARRTP] facility has a single entrance. It has a camera there to monitor everyone’s coming and going. And while patients can leave the center, they’re searched when they get back to ensure they’re not bringing in any contraband.

The details in the report are too blurry to identify the vet involved. But the few specifics are clear enough: He spent several months in early 2013 in the SARRTP unit, after he had bounced from the VA’s Psychosocial Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program to the VA’s PTSD Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program then to the VA’s acute inpatient mental health unit.

The VA’s goal: get him “into PTSD residential treatment once he improves coping skills, mood stability, and functioning.” He never made it. Perhaps his craving to get high would have doomed him in any event. But the VA’s inaction, as detailed in the following excerpts from the IG’s report, guaranteed his failure:

The patient was an Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) combat veteran in his twenties, who was diagnosed with polysubstance dependence, PTSD, sleep apnea, mood disorder and traumatic brain injury.

We found that camera surveillance was not present as required. VHA [the VA’s Veterans Health Administration] policy requires that RRTP [Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program] unit entrance doors be monitored by Closed Circuit Television (CCTV). Additionally, CCTV with recording capability must be used to monitor RRTP public areas such as hallways. Local policy mandates that closed circuit video cameras be focused on each MHRRTP [Mental Health Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program] entrance and hallway and viewed and recorded in Police Service. The recordings are to be kept for at least 2 weeks.

Upon admission to the SARRTP, UDS [urine drug screen] results were negative for illicit substances.

We met with Police Service staff to review the surveillance conducted on the SARRTP unit. A Police Service employee was unable to correctly identify which screen was showing feed from the SARRTP. We were subsequently told by the Chief of Police that the camera which monitors the main hallway on the SARRTP unit had been inoperable since at least December 2012.

Two days later, UDS results were positive for cocaine.

The Police Service employee who was monitoring the CCTV feeds at the time of our visit was unaware the SARRTP camera was inoperable. Similarly, key SARRTP staff were unaware that the camera was inoperable, including the Nurse Manager.

The SARRTP psychiatrist addressed the results with the patient.

VA Handbook 0730 requires that when surveillance television systems are in use, performance checks be conducted daily and substitute coverage be provided during maintenance or breakdown periods. We found no evidence that the facility provided substitute coverage or other means of securing the unit during camera failure.

The patient admitted that he used cocaine after admission to the SARRTP.

We found that access to the SARRTP was not monitored or controlled appropriately.

He had left the unit to pick up money that had been wired to him and used the funds to purchase cocaine.

Access to the SARRTP unit is controlled by a keyless entry badge-activated system. Individuals without a badge ring a buzzer and request entrance. Local policy states that only authorized patients, staff, and visitors may be allowed access to the unit.

He was placed on pass restriction (no overnight or weekend passes) for 3 weeks.

At the time of our inspection, we visited the SARRTP unit twice unannounced. SARRTP staff did not request identification or verify the purpose of the visit on either occasion. During a day shift visit, an OIG [Office of the Inspector General] inspector was “buzzed in” without displaying a badge or credentials or explaining the reason for the visit; the inspector walked through the unit and after several minutes, approached unit staff to identify himself.

However, the veteran was permitted to leave the unit for up to 2 hours without a pass.

During the evening shift, three inspectors, dressed in casual clothes and not wearing badges, followed two patients into the unit without SARRTP staff’s knowledge of an unauthorized entry.

UDS results from the next month were again positive for cocaine.

During staff interviews, we learned that SARRTP staff on evening, night, and weekend tours routinely sit in a back room that does not have visibility of most of the main hallway of the unit, nor the entrance and exit doors. During our evening site visit, we found the staff in this back room. Had the staff been present at the nurses’ station, they would have been able to observe and monitor the main hallway and entrance and exit doors.

The SARRTP psychologist addressed this with the patient and he was placed back on pass restriction for another three weeks.

We found that patients’ whereabouts were not being monitored as required. VHA requires that RRTP programs have a system for tracking the whereabouts of patients, typically by maintaining a sign-in and sign-out list. Local policy states that patients can sign themselves off the unit for up to 2 hours without a pass but must include their destination, remain on campus, and sign back in upon return so that their whereabouts are always known to staff. We found that the sign in/sign out list on the SARRTP unit was not being reviewed by staff for suspicious activity (patterns of leaving the unit) and that patients did not consistently sign in/sign out. The sign in/sign out entries that we observed did not include dates.

The day before his death, the patient left the SARRTP on a pass in the early afternoon.

We found a lack of consistency among staff in performing contraband searches. According to local policy, nursing staff will conduct and document inspections of all patients being admitted to the program and returning from pass in order to detect any possible contraband that could be brought onto the unit.

Upon his return that evening, a breathalyzer test was completed with negative results (no alcohol detected).

We interviewed staff to determine how contraband searches were conducted upon a patient’s return from pass and received conflicting information. Several staff reported that they were not permitted to search patients’ pockets or to request patients to empty their pockets as this was equivalent to a body search and not allowed. However, the RRTP Program Manager told us that he expected pockets to be emptied as part of a routine contraband search.

A staff nurse documented at that time, “bag(s) checked: no.”

We also found that the EHR [electronic health records] template progress note used to document whether bags had been searched upon a patient’s return from pass was unclear. A line item in a note stated “bag(s) checked: no.” We could not determine from the “no” documentation if there were no bags to check or that bags were not searched.

SARRTP patients who were interviewed by CID [Criminal Investigations Division] agents reported that while on the SARRTP that evening, the patient was intoxicated from illicit drugs and required assistance to get into bed.

We found that the methods used for monitoring SARRTP patients for illicit drug use could be strengthened. UDS were collected every Sunday in the late afternoon or early evening. Staff told us they were consistent with the time of day and day of the week for collections. As the timing of the collection was predictable, patients were aware of when the UDS would be done and could modify their behavior accordingly. Some random UDS were collected during the week, but staff told us this tended to be on the same days of the week, so the pattern of collection times was again fairly predictable.

The patient was found dead in his room on the SARRTP unit the next morning.

The facility is located in a part of Miami with reported high drug activity. Patients who are allowed to leave the unit unsupervised have potentially easy access to illicit drugs. We reviewed the EHRs of other patients in the SARRTP at the time of the patient’s death to determine the extent of illicit drug use among patients. In addition to the patient under review, we found that 7 of 21 patients had a positive UDS and/or breathalyzer test at some point in their substance abuse program stay. Five additional patients had a positive UDS but were not included in the 33 percent positive result category, as either the UDS was completed at admission and positive results could have been from drug use prior to admission or patients were prescribed medications that are associated with a false positive result.

The medical examiner determined that the official cause of death was acute cocaine and heroin toxicity.

SARRTPs should provide a safe recovery environment for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders who require a controlled and sober environment.

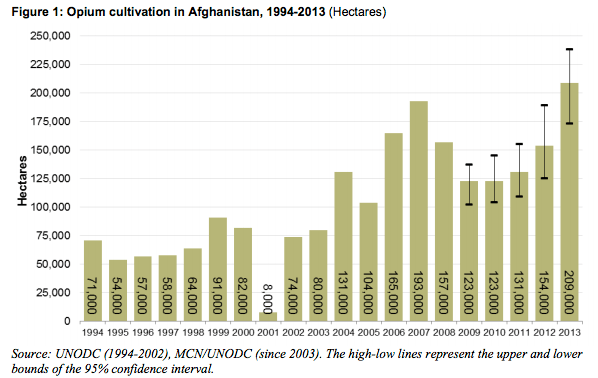

It’s unnerving that heroin helped kill this Afghan vet. Afghanistan is the source of about 80% of the world’s heroin. Poor Afghan farmers dedicated more than 500,000 acres to the opium poppy’s cultivation in 2013. That’s up 36% from 2012.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com