The Zika virus has spread rapidly, sparking alarm over the confirmed link between the virus and the birth defect microcephaly. Though the disease, which can be transmitted sexually and by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, causes minor symptoms for most people who are infected, the potential consequences for pregnant women and their unborn children are severe, prompting travel warnings. As Puerto Rico readies itself for summer, worry grows that Zika will spread widely in that country — and possibly to other parts of the U.S.

TIME spoke with Dr. Tom Frieden, head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about how it will affect Americans, the Obama Administration’s request for $1.9 billion to fight Zika — and what happens next.

Puerto Rico is expected to get hit hard with Zika. But experts are saying it won’t likely spread widely in the continental U.S. Why?

The way Zika spreads is primarily through the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito in places that don’t have screens and air-conditioning. So while we anticipate that there could be local clusters of Zika in the United States — and there have already been several sexually transmitted cases of Zika — widespread transmission generally occurs in places with many more of these types of mosquitoes and much less air-conditioning and screening.

Should Americans who don’t live in places with that kind of mosquito be concerned? Could other types carry the virus?

Know that the tiger mosquito — Aedes albopictus — sometimes spreads viruses that spread like Zika, so it may be able to spread Zika.

What efforts are being made to kill mosquitoes where they breed in the U.S.?

Mosquito control in the United States is very much a local and state activity. Some states have excellent programs, other states not so much. It’s one of the reasons it’s so urgent to identify and spread best practices to try and track and reduce mosquito populations.

Do states have what they need to do adequate mosquito control and surveillance? Maps of Aedes aegypti in the U.S. are incomplete, so it’s hard for people to know exactly where they are.

There are major needs. We have reprogrammed money as a stopgap measure. It is crucial Congress approves the supplemental request. We are working with states and others to update those surveillance maps, but it takes time. It’s not a onetime thing. You have to set up a surveillance system that continues over months and years because sometimes the mosquitoes come and go. One of the challenges in tracking for this particular mosquito is it’s very local. It only flies a couple hundred yards in its whole life. You have to look in many places to find where it might be.

What do you think of some of the next-generation technologies for getting rid of the mosquito, like the genetically modified mosquito, for example?

I hope they work. I am not counting on them. They should certainly be pursued, but of greater immediate value will be mixing and matching today’s tools to protect people as well as possible. Let me give you our bottom line here. Our top priority will be to protect pregnant women and the developing fetus. We can do that by — for women in parts of the U.S. like Puerto Rico where Zika is spreading — helping them reduce the likelihood they will get bitten by an infected mosquito, and for women who choose not to get pregnant, increasing their access to voluntary affective contraception. Right now that access is very low in Puerto Rico.

A big issue in the U.S., which is up in front of the Supreme Court, is access to clinics that provide contraceptives and abortions. Is this of concern to you amid Zika?

Access to voluntary contraception is obviously extremely important to women who choose to wait to become pregnant.

Is there an internal debate about whether American women should put off pregnancy?

I think the debate, as far as there is a debate, is more what to recommend in places like Puerto Rico. If in fact over the next few years it’s going to spread widely through the island, and if you really didn’t want to get pregnant, I think everyone would agree that it’s a reasonable thing to wait. But I think everyone would also agree that this is a decision for the woman and her partner to make and not for government officials. In conjunction with her doctor, obviously.

There are concerns regarding DEET’s potency. Is it safe for pregnant women?

Yes.

Recently, the CDC hosted state experts to discuss how to prepare for Zika. One expert mentioned that the U.S. used to have an Aedes aegypti eradication program, which you said was “eradicated before the mosquito.” Has the capacity to fight mosquitoes and conduct surveillance diminished in the U.S.?

I would say it has waxed and waned. If you go back to the ’40s and ’50s, we used large amounts of DDT. It was also used agriculturally, and it’s a very controversial area, but the big problems came from agricultural use — not so much public-health use. But the mosquitoes also developed resistance. Now, for example, the mosquitoes in Puerto Rico are resistant to DDT even though it hasn’t been used there in decades. There are different approaches, and there’s a better understanding of the risks and benefits of all forms of vector control. There is no magic bullet here. We need a series of interventions.

Some cities in the U.S. have funds to conduct quality mosquito control, but others do not. How can Zika be prevented from becoming a problem for the poor, particularly?

Well, that’s really a question not just about Zika but many diseases. If you look at the outbreak of dengue in Brownsville, Texas, people in Brownsville were much more likely to get dengue if they were living in crowded quarters. So we have to prioritize the populations that are at the greatest risk for Zika both for their own sake and for all of ours.

How will we actually know if mosquitoes in the U.S. are spreading Zika?

If there’s a case analyzed, and we can see whether it’s sexual, travel or mosquito. And if there is local transmission by mosquito, then there should be a rapid and robust local response.

Is it possible that Zika is transmitting more via sex than we currently realize?

Not in the U.S. I think we would know it was doing that in the U.S. It may be that some of the cases globally are sexual whereas we assumed it was mosquito. The cases we’ve seen have all been from men around the time they were symptomatic. It doesn’t suggest that it’s likely to have been a major cause of the number of cases. One thing that makes it hard to track that is that because we are most concerned about pregnant women, we are testing more pregnant women. We find more women testing positive than men, but that doesn’t mean that there’s a lot of sexual transmission.

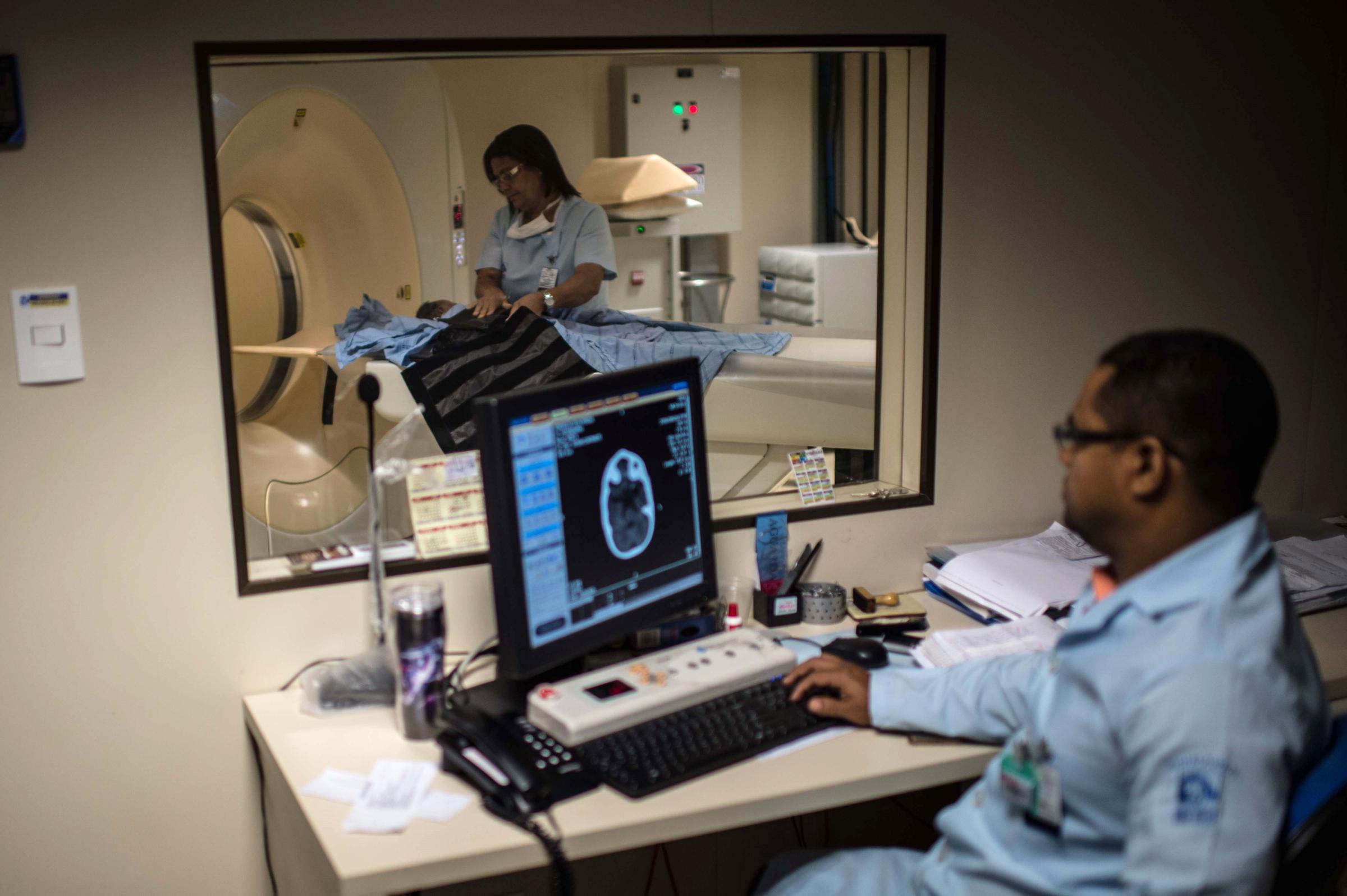

See the Impact of Zika in Brazil

Recent research has linked Zika to a variety of brain issues. Can we expect to see more?

We expect Zika will be just part of a spectrum.

What are your long-term concerns about diseases like Zika in the U.S., given situations like climate change, people moving, etc.

We expect that with urbanization and travel, mosquito-borne diseases will continue to be important challenges for Americans to be protected against. That’s why Congress rapidly approving supplemental funding is so important.

What do we know about why some pregnant women with Zika have a baby with microcephaly and others do not?

That is what we are studying now. We will look at things like risk factors, time in pregnancy [of infection]. It’s going to take many months to determine what causes it.

For non-pregnant women and men, how confident are we that there are no long-term effects?

Well, if it behaves as other viruses do, prior infection will probably result in long lasting immunity and no harmful effects. But we just issued recommendations and details about women who had recent exposure and recent infection. Reasonable is waiting a short period of time before conceiving just to be on the safe side.

What do Americans need to know about Zika right now?

I think the key thing is that we wish we had more answers. We are working 24/7 to learn more and protect women and their developing fetus as well as possible. Zika is a very challenging virus to fight.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com