This piece is part of an ongoing series on the unsung women of history. Read more here.

On her first trip away from her home in Ohio, in the early 1950s, a teenaged Muriel Siebert visited the New York Stock Exchange. Later, in her autobiography, she would recall the trading floor, seen from above, as a “sea of men in dark suits,” resounding with the “clamorous human buzz of… thousands of deals.” She declared to her friends that one day she’d come back there and ask for a job. Why not? The souvenir in her hand was a piece of ticker tape with her name printed on it, along with the words: “Welcome to the NYSE.” She held on to it throughout her career, clearly relishing the irony. Nobody made Muriel “Mickie” Siebert welcome on Wall Street. Every door that opened for her was one she kicked down for herself.

In 1954, Siebert returned to New York in a second-hand Studebaker to put her plan into action. There were women working on Wall Street as secretaries and support staff, but she hadn’t come all that way to help with someone else’s job. At university in Ohio she’d taken classes in business and was used to being the only girl in the room. But this was what she was born to do: “I could look at a page of numbers, and they would light up like a Broadway marquee,” she wrote later. She left college early when her father was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and didn’t take her degree, but in New York she quickly learned to fudge that detail. She landed a job as a researcher, at $65 a week, at the firm of Bache & Co. Paying attention to accounts that other people overlooked, especially in the fledgling aviation industry, she watched and learned.

By the mid-1960s, having switched firms several times, Siebert was ready to purchase her own seat on the stock exchange, which would allow her to buy and sell shares directly on the trading floor. There was no specific rule against a woman doing so—she checked—but she needed a backer, and went through nine male colleagues before one said yes. Small wonder that even after she clawed her way to her seat, in 1967, she remained the lone woman alongside 1,365 men for the next decade. The symbol of her exclusion was the ladies’ room, or lack of one, on the trading floor. “Not since I was a baby had so many people been so interested in my bathroom habits,” she recalled wryly. (Of course, no amount of paternalistic concern for her physical comfort prompted anyone to update the plumbing. A full 20 years later, there was still no ladies’ room on the seventh floor of the stock exchange, where the lunch club was located, until Siebert threatened to install a Porta-Potty.)

Siebert’s career can be tracked through articles about the changing status of women in the workplace. In 1968, when TIME examined the “outright or subtle discrimination” working women faced, it highlighted another of her signature fights: women’s access to the important deal-making that went on in the city’s all-male lunch clubs. Being Jewish only highlighted Siebert’s sense of exclusion, during years in which anti-Semitism was commonplace in the corporate world. By 2008, TIME again pointed to Siebert, this time to show how far the finance world had come. The magazine noted that one-third of the young professionals working on Wall Street were women—although as the head of her own firm, Siebert was still a rarity.

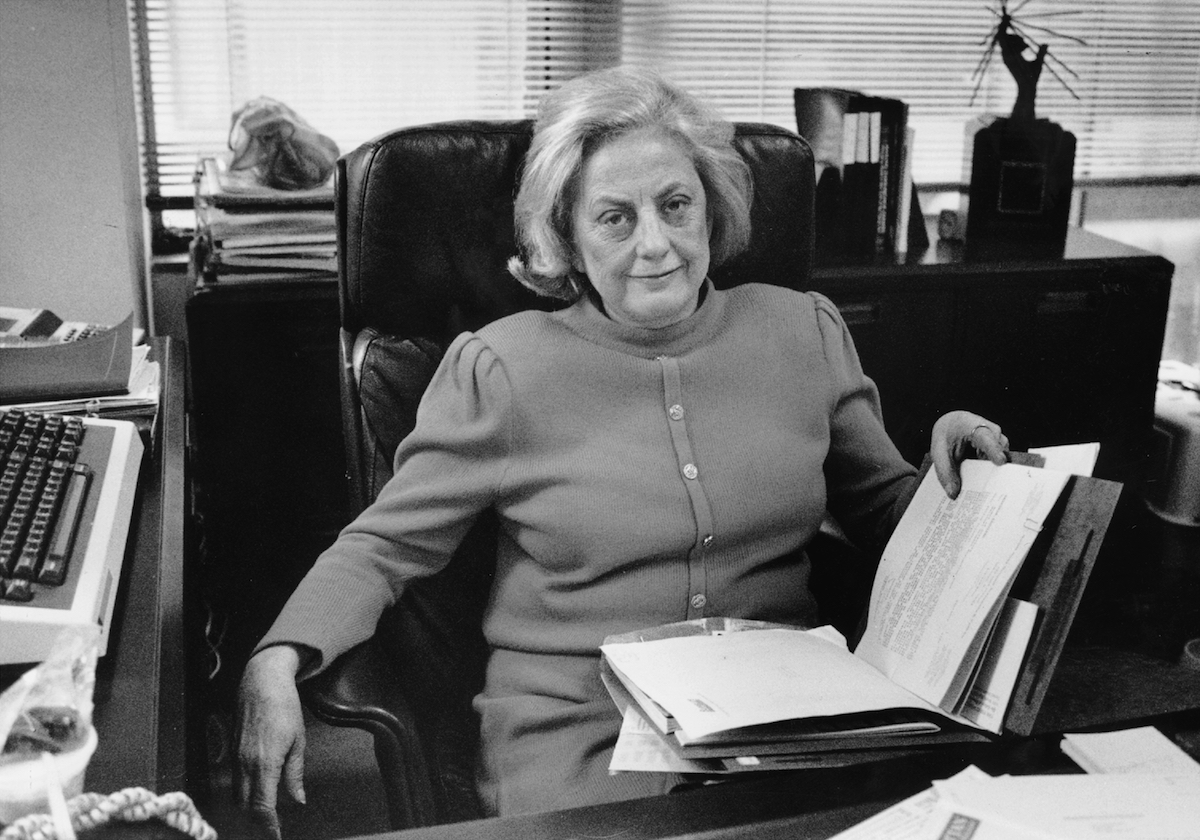

In 1977, Siebert stepped aside from running her firm to serve as New York’s first female superintendent of banking, and took great pride in the fact that no banks failed during the five financially rocky years of her tenure. After a failed run at the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate, she returned to her brokerage firm, and resumed fighting campaigns her own way: with money and chutzpah, both of which she had in ample supply. She spent a large chunk of her fortune funding women in business, promoting financial literacy and supporting animal-welfare charities. Siebert was inseparable from her longhaired Chihuahua, Monster Girl (followed by Monster Girl 2)—a kindred spirit of a creature, that couldn’t be cowed by “the big dogs.”

When she died in 2013 at the age of 84 (not 80, as first reported—throughout her career she’d found it useful to shave four years off her age), Siebert was celebrated as a trailblazer. But her own word for herself—maverick—might be closer to the truth. The Enron scandal, which she discussed in the final pages of her 2003 autobiography, shocked her to the core, and in 2008 she argued that the instigators of the financial crisis should go to jail. Progress, she knew, wasn’t as simple as helping other women follow in her path, because their fights would not be the same as hers. “You have to keep fighting,” as she told an audience in 1992, warning them against complacency. The ladies’ room was just the beginning.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com