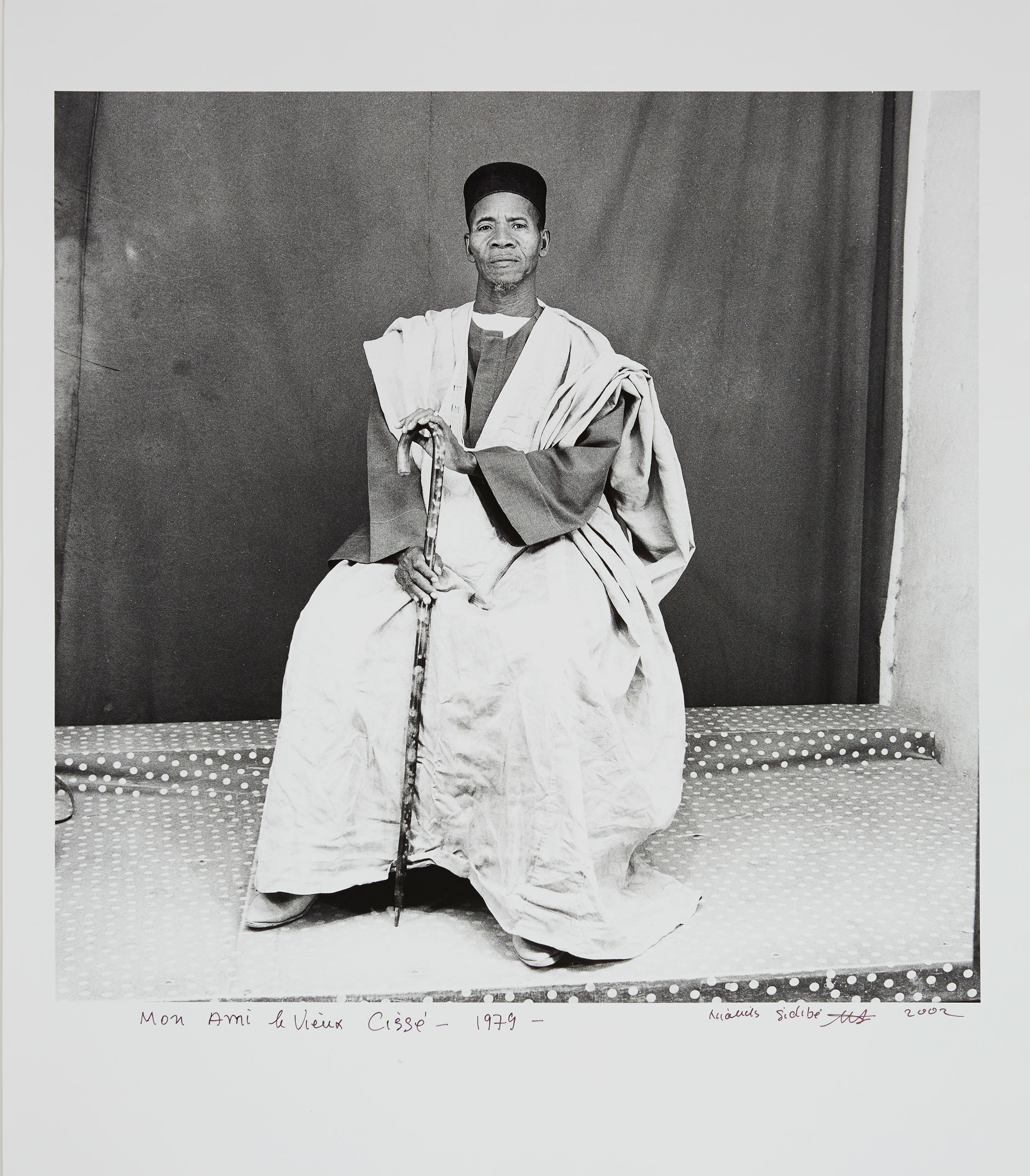

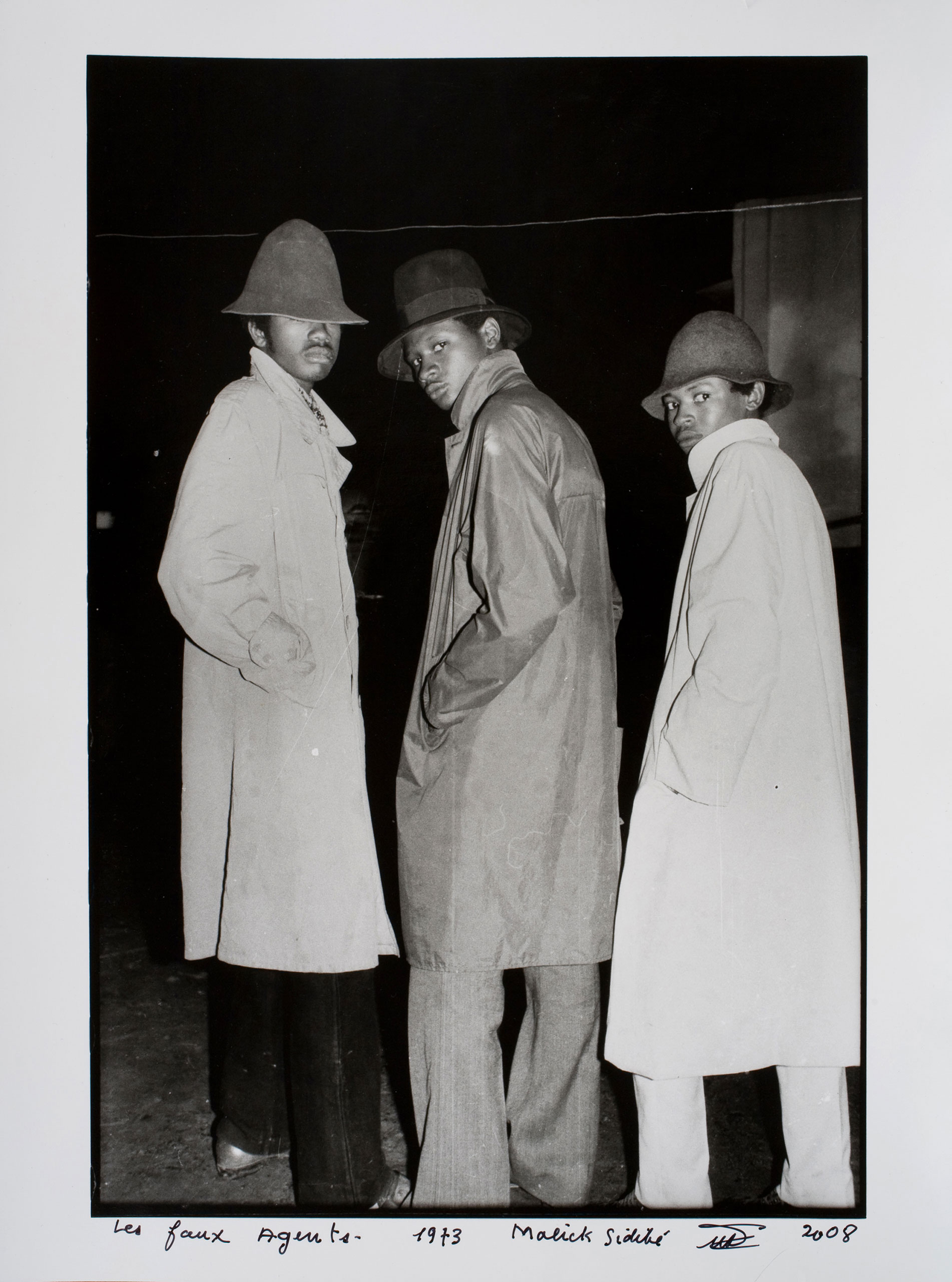

Away from the formalities of conventional portrait photography, away from the clichés of colonialism imagery, Malick Sidibé’s pictures of Mali’s youth conveyed the high-spirited feeling of a country that has just gained its independence. Over the years, his black-and-white pictures have influenced many of his contemporaries in Africa and beyond. Now, almost 60 years after he first opened a photography studio in Bamako, Sidibé has died of complications of diabetes, the Associated Press reports. He was 80.

“It’s a great loss for Mali. He was part of our cultural heritage,” said Mali’s culture minister N’Diaye Ramatoulaye Diallo, according to The Guardian. “ The whole of Mali is in mourning.”

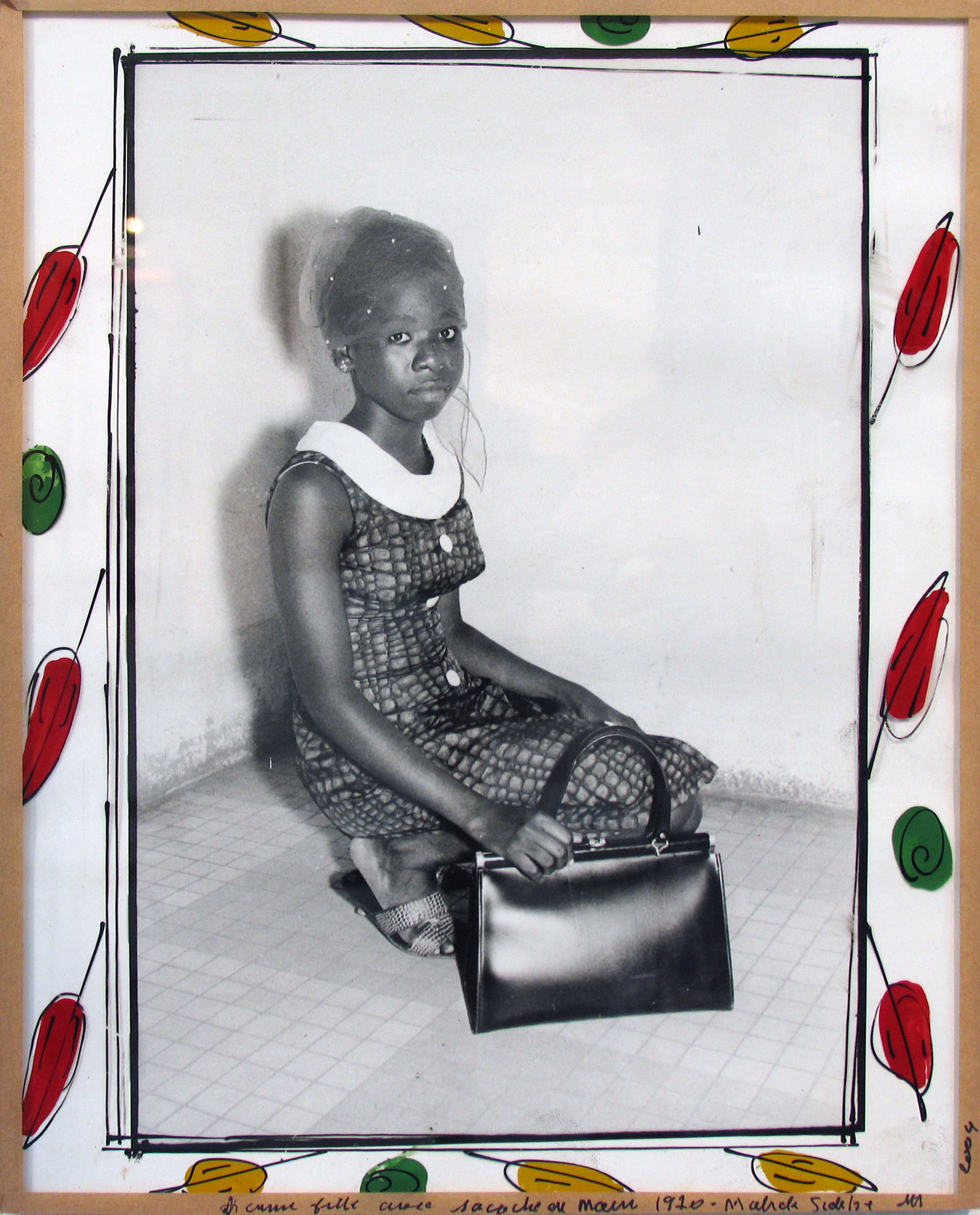

“A witness of his country’s effervescent independence, and among the young folk besotted with music, Malick Sidibé photographed the parties and joys of Bamako,” French culture minister Audrey Azoulay added in a statement. “A master of portraiture, he showered his studio’s visitors with his kind and benevolent gaze. I send my heartfelt condolences to his relatives.”

Born to a peasant family in what was then French Sudan in 1935 or 1936, he left his shepherding duties at the age of 10, to study at a colonial school at which he was one of very few non-white students. His artistic talent was quickly noticed and he won a place at École des Artisans Soudanais in Bamako in 1952. The course of his career changed when he was approached by society photographer Gérard Guillat, who asked him to become his apprentice.

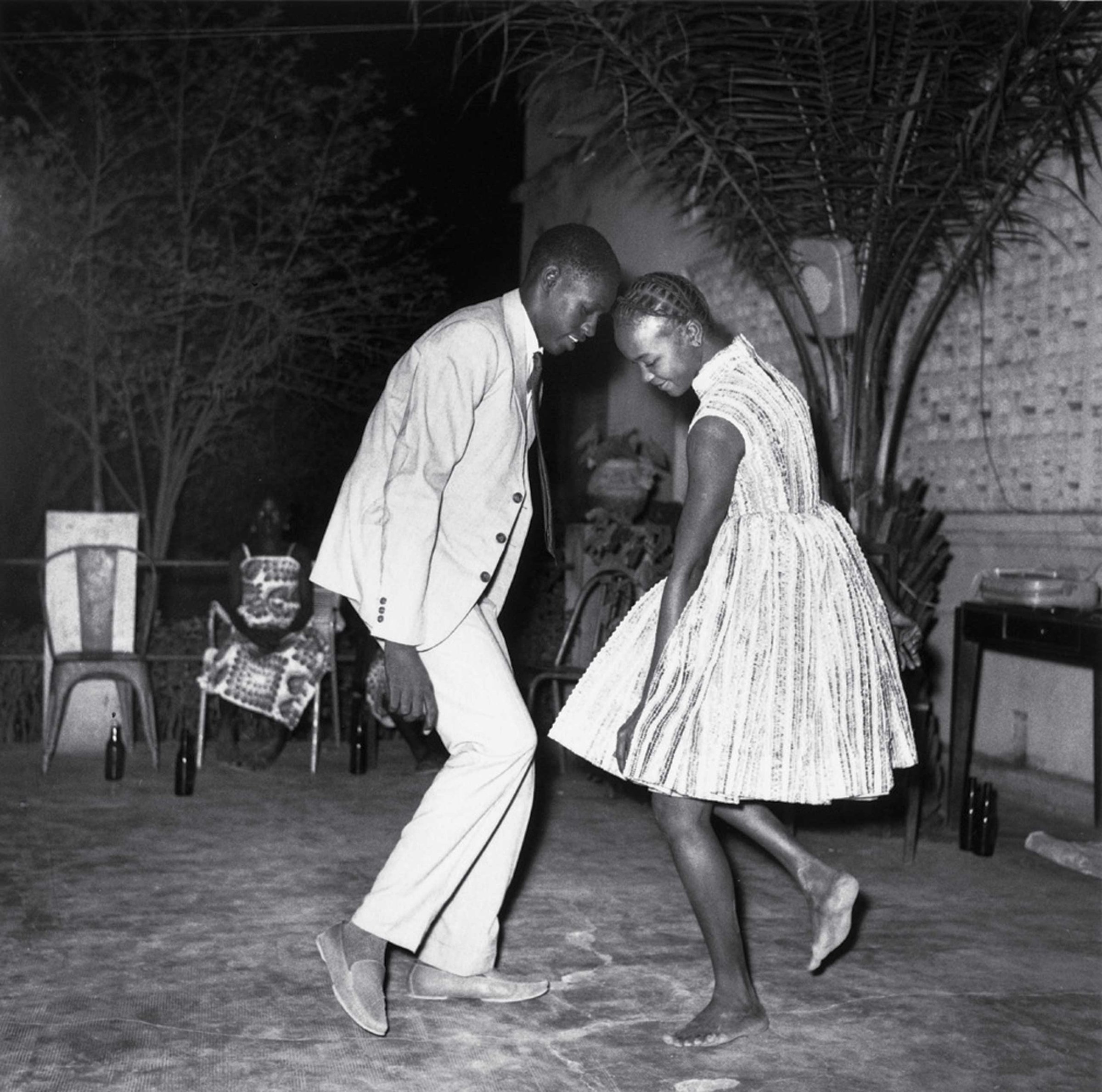

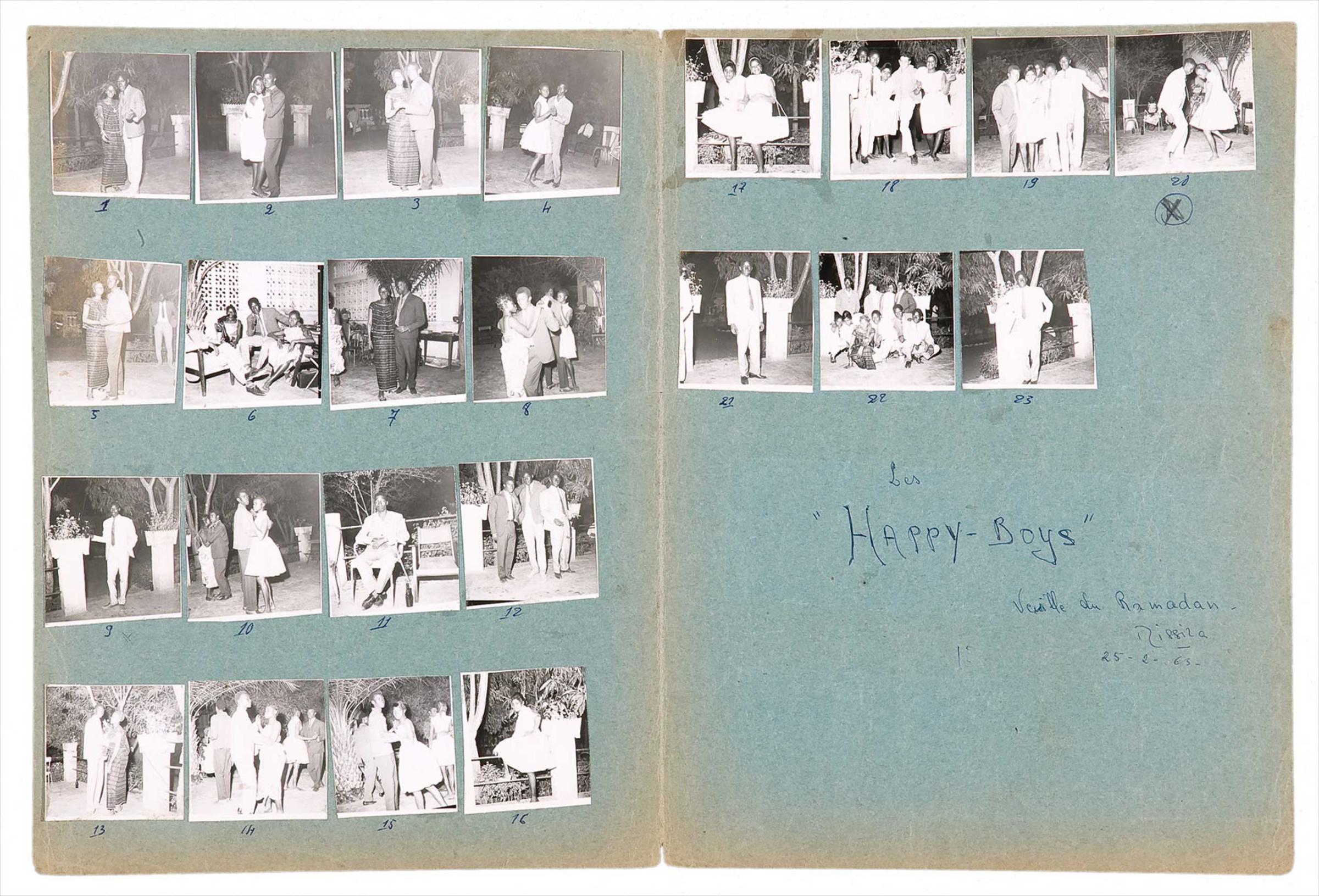

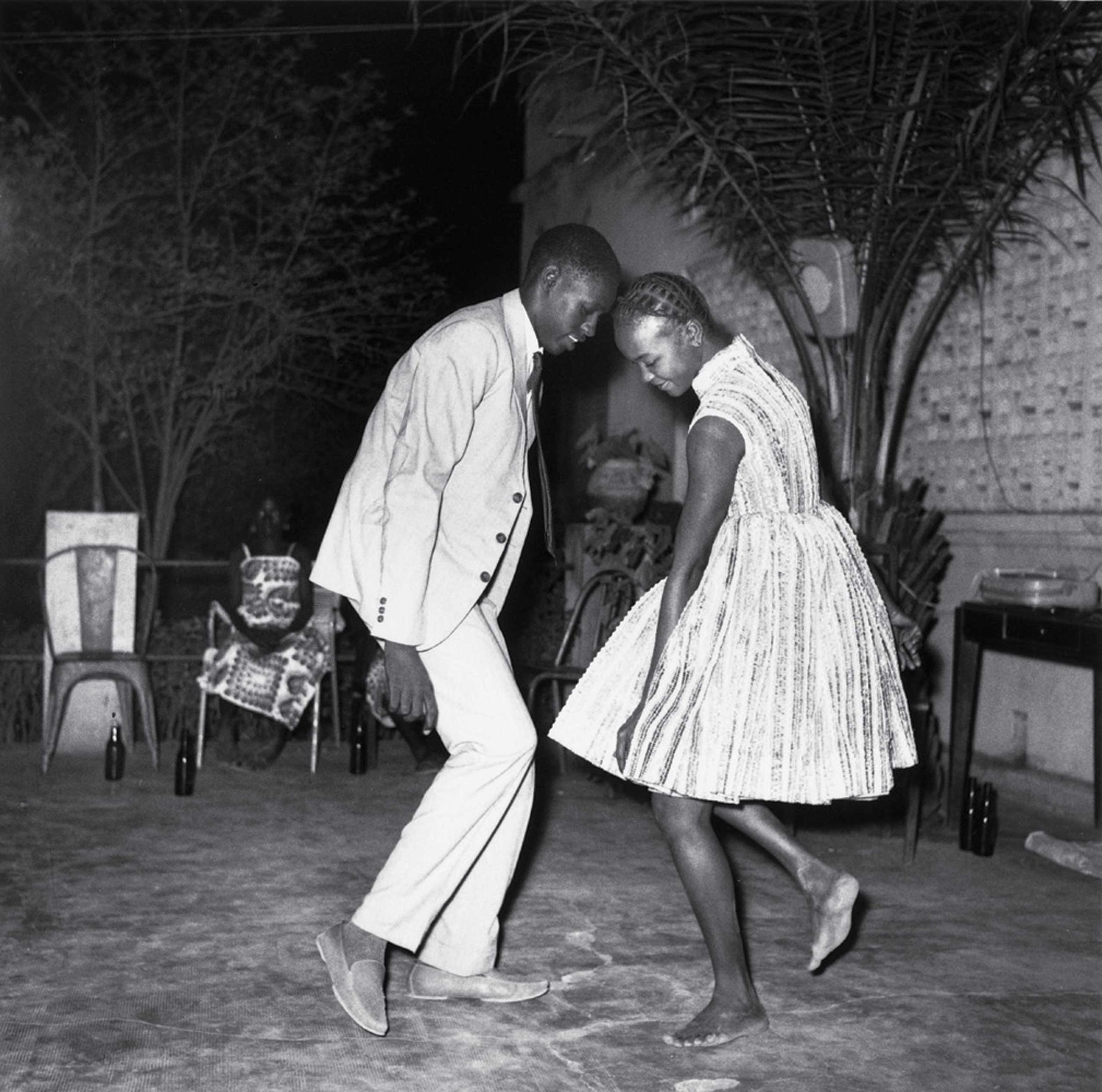

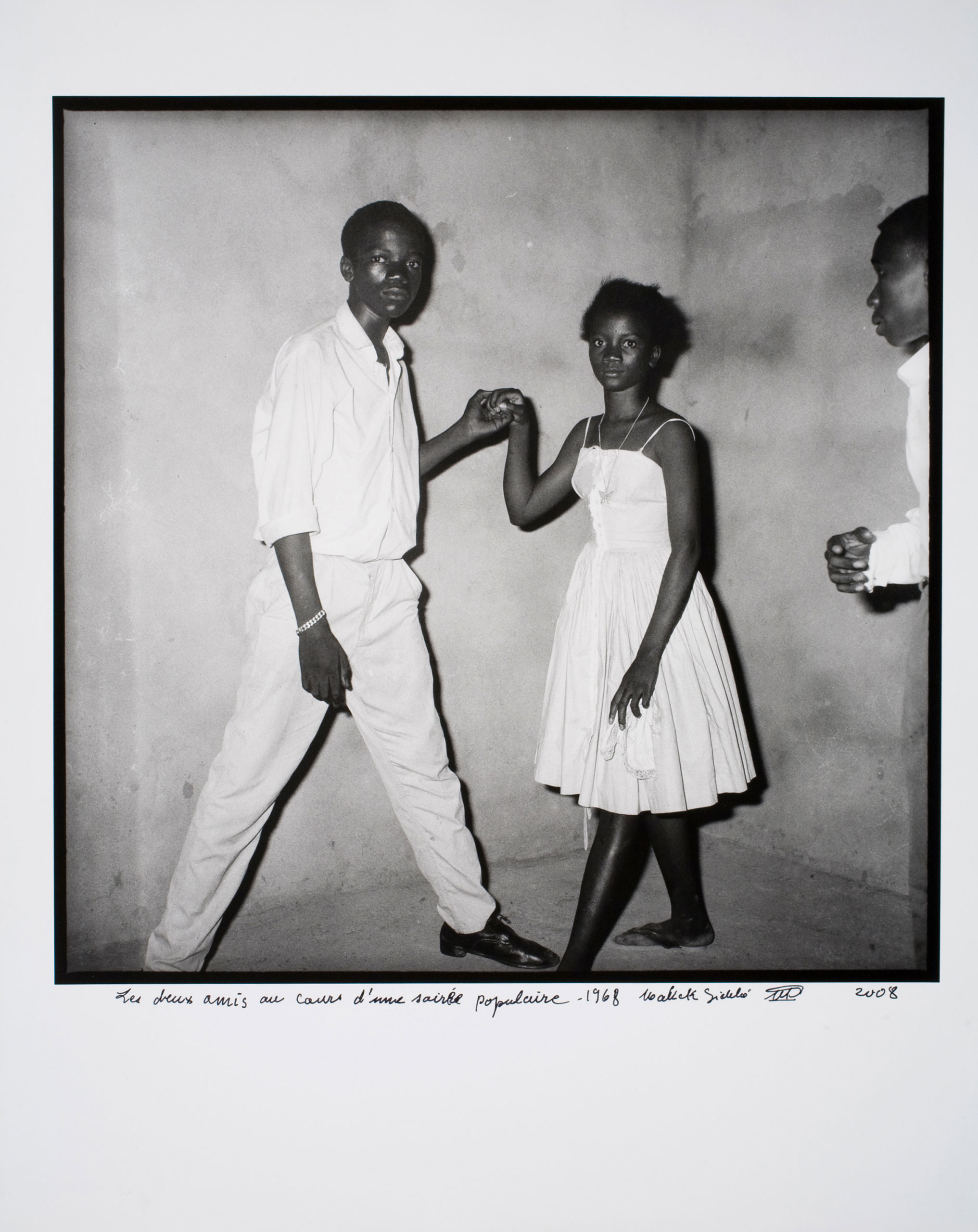

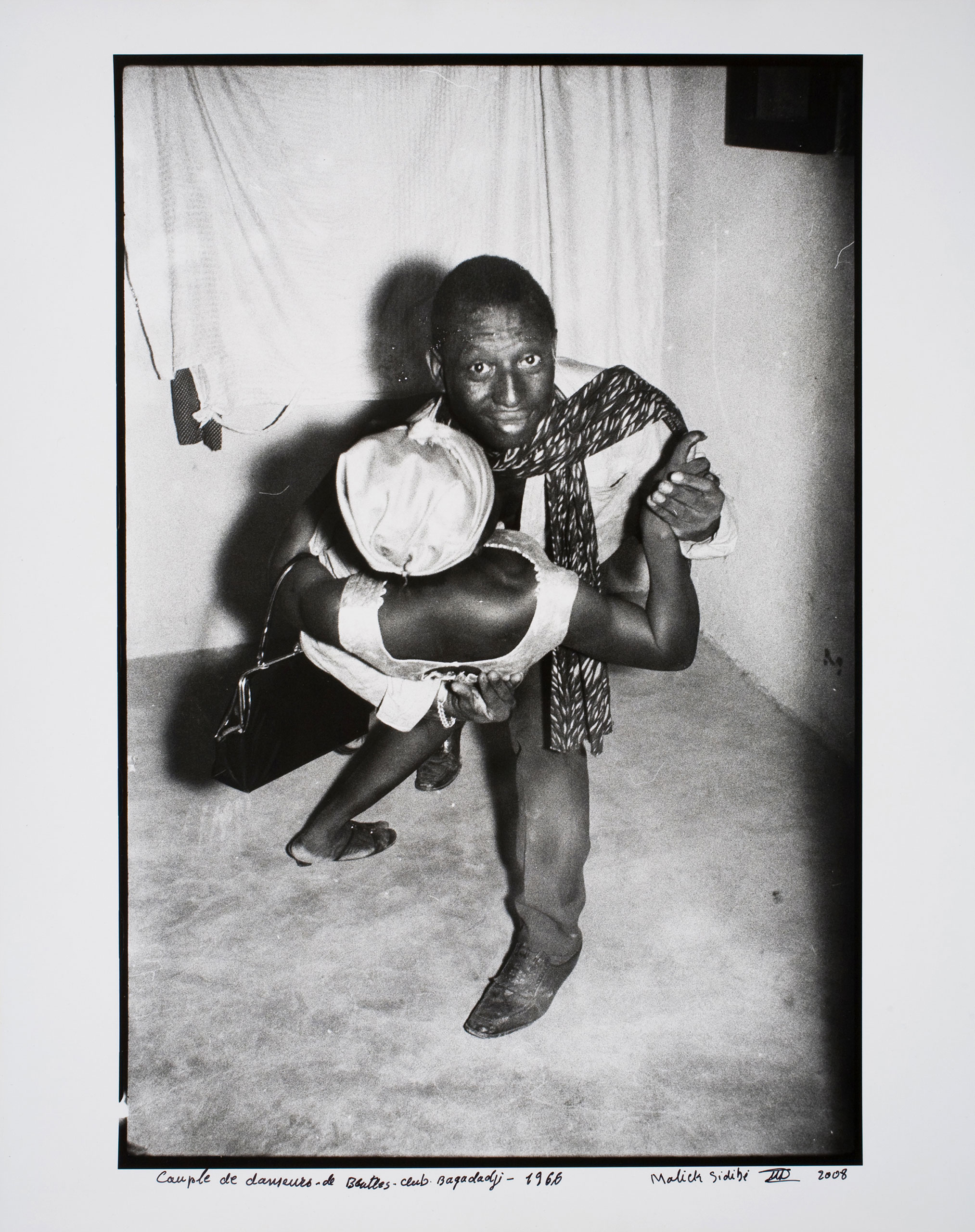

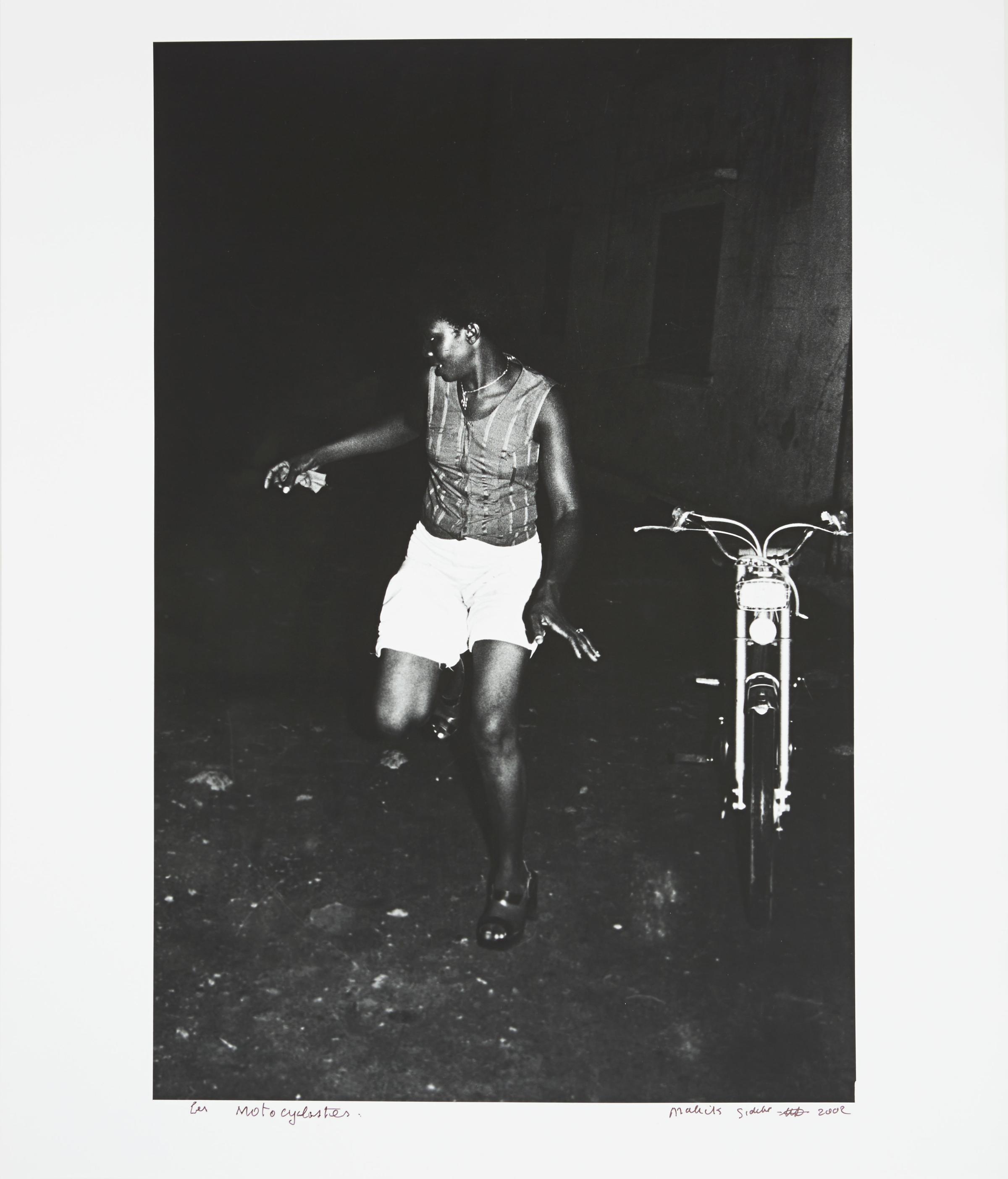

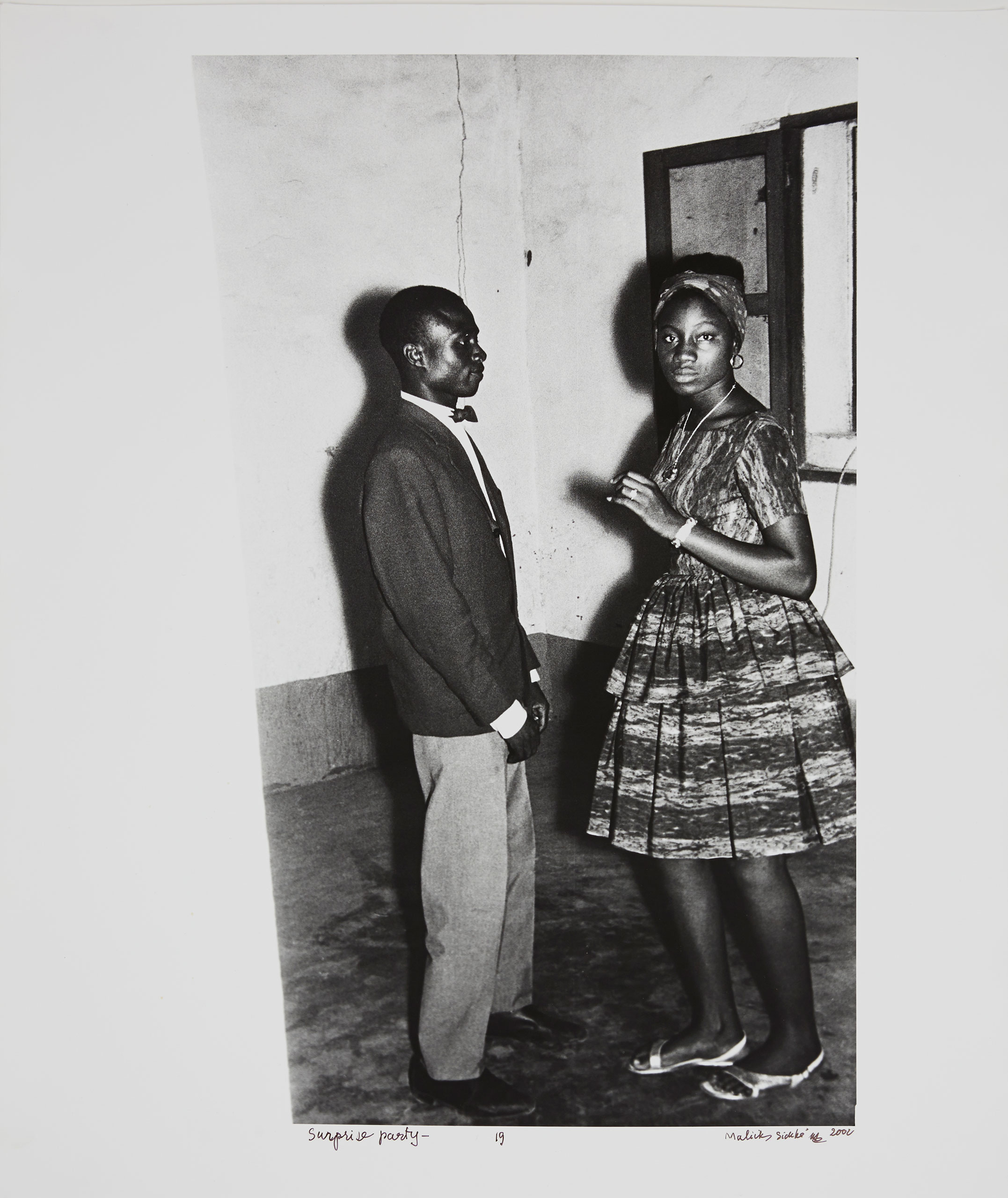

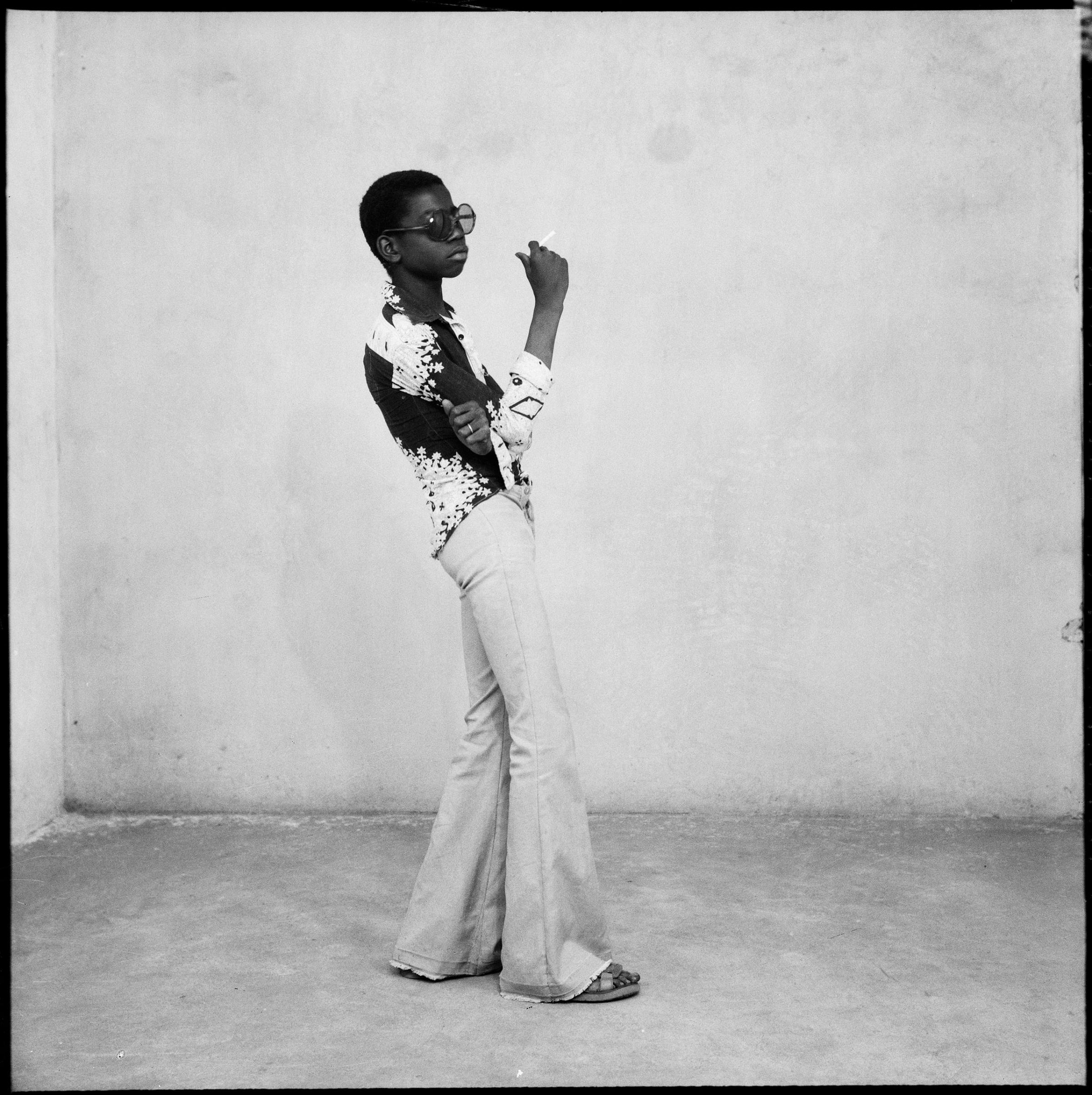

While working at the studio, Sidibé cycled to nightclubs in Bamako in the evenings, photographing party-goers with his first camera, a Brownie Flash. He became known as “the Eye of Bamako,” famous for his documentary-style photography that offered a rare glimpse into African youth culture, from concerts to nightclubs to sports events. With the coming of Malian independence in 1960, those images took on a deeper layer of meaning.

“We were entering a new era, and people wanted to dance,” Sidibé once said. “Music freed us. Suddenly, young men could get close to young women, hold them in their hands. Before, it was not allowed. And everyone wanted to be photographed dancing up close.”

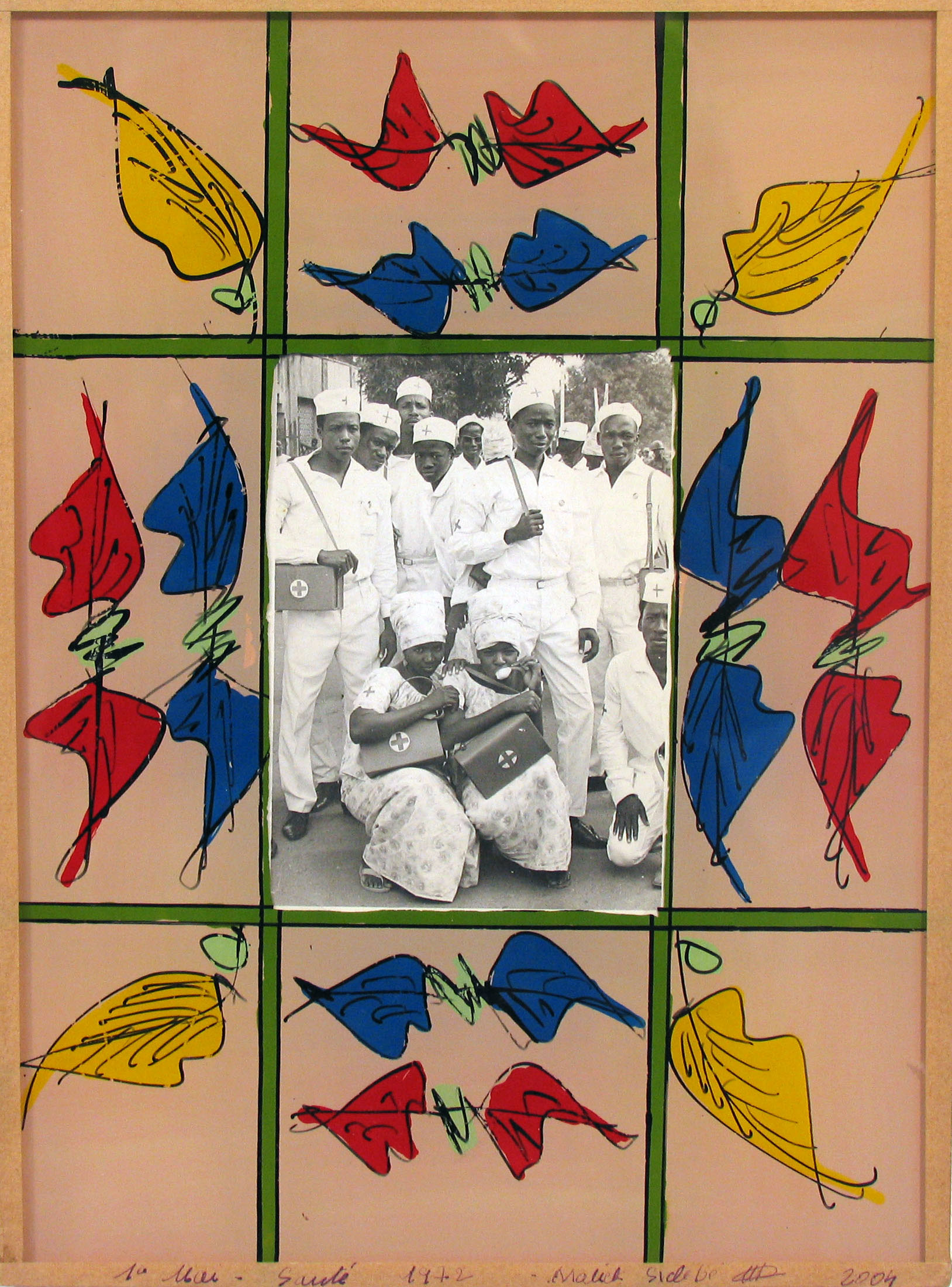

His incommensurable work spanning six decades — currently showing at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York — gained the international recognition it deserved in 2003 when he received the prestigious Hasselblad Award and four years later when La Biennale di Venezia awarded him the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement Award. He was the first photographer to have received this distinction.

“For many people who know something about photography — Africans and non-Africans alike — Malick Sidibé’s work was the very embodiment of African photography. In part this is because of the profound humanistic spirit of his images and the spark and originality of his vision,” says John Edwin Mason, a writer and professor of African History at the University of Virginia. Though many westerners may have been fired drawn in by the idea that Sidibé’s work was exotic or “unsettling,” in some ways, Mason says, they would soon find just the opposite to be true. “Ultimately, however, [audiences] have embraced the ways in which Sidibé’s photographs confirm our shared humanity.”

“He reminded me so much of my own father which is why I think I spent time with him,” says Jehad Nga, a photographer who became friends with Sidibé after they met in 2011. “We sat once and went through one of his books, which is a chronicle of Mali’s history. Like every book he shared with me, it took hours to get through it. At every page, he would stop and light up while telling the story behind the frame. Frame by frame, he recalled who and where. He would pore over it as if seeing it for the first time.”

Inside the Photographer’s Studio: Malick Sidibe

Up until his last days, Sidibé lived and worked in the same one-room studio, welcoming any and all visitors and surrounded by his family and neighbors, “light years from the art centers of the world,” as Nga wrote in 2014. And, Nga tells TIME, Sidibé still had big plans for the future. Recently, he shared his ideas for a new book based off of old works.

Sidibé, who leaves behind three wives and 17 children, will be buried in his natal village, Soloba.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com