HBO’s new film Confirmation, which premieres Saturday, pulls much of its dialogue directly from the transcripts of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ 1991 confirmation hearings, during which Professor Anita Hill claimed that Thomas had sexually harassed her. The film, starring Kerry Washington, also nods toward the legacy of those hearings, such as the groundswell of support for female senatorial candidates who ran on platforms of gender equality in the years that followed.

MORE: Anita Hill on Confirmation, What Joe Biden Did Wrong and the Clintons

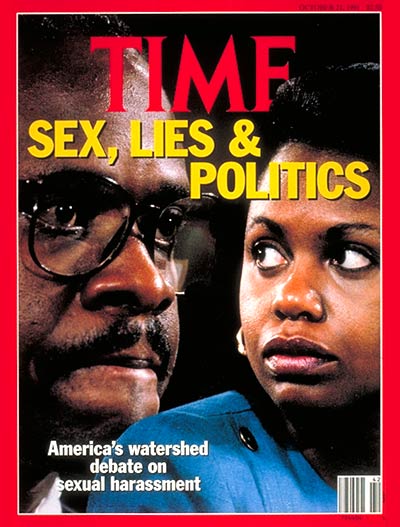

Though it’s often the case that historical turning points are only identifiable in retrospect, journalists at the time were able to pinpoint the moment as an important one for feminism in America. TIME published a series of articles on the hearings in September of 1991. Here are just a few of the ways those stories predicted the fallout from the hearings and the legacy that is still felt 25 years later.

The problem of “he said, she said”

The question of who exactly was telling the truth was perhaps the most important issue in 1991. “For witnesses to this spectacle, whether there in the Senate Caucus Room or at home in their living rooms, deciding who was telling the truth was all but impossible,” Jill Smolowe wrote of the two credible witnesses. Both Thomas and Hill called on others to testify about their character, but the committee, notably, did not call several other women who claimed to have experienced similar treatment working under Thomas to testify. In investigating the backgrounds of both Hill and Thomas, Richard Lacayo found that each had a reputation among friends and colleagues for truthfulness and integrity. Friends of Hill, especially, emphasized she was “cut from the same political cloth as Thomas” and unlikely to bring false charges against him to help the democrats.

This back and forth predicted the problems our legal system has in cases of sexual harassment and assault—issues we continue to see today, especially on college campuses as schools try to adjudicate assault accusations.

A private conversation becomes public

When issues often whispered in office halls were suddenly being debated on live TV, workplaces across the country were confronted with the question of how to deal with sexual harassment, according to reporting from TIME’s now-Editor Nancy Gibbs: “In America’s workplaces, men and women reintroduced themselves with a suspicion that their relationships had changed forever.” Though there had already been laws in place against sexual harassment, what exactly qualified as harassment was unclear. The 1991 article outlined what was not allowed, from comments and propositions to touching and the display of pinups. The issue even included a workplace etiquette guide, advising workers on what to do if propositioned by a boss.

After Hill’s testimony, sexual harassment claims at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission—coincidentally the agency where Hill worked for Thomas—skyrocketed. Perhaps even more importantly, her testimony made the statement that powerful men could be held accountable for their behavior. Congress passed the Government Accountability Act four years later, which stated that Congress is subject to the same discrimination laws as the rest of the country.

MORE: A Brief History of Sexual Harassment in America Before Anita Hill

The “Year of the Woman”

It was immediately clear to many viewers at home that the 14 white men who sat on the committee, led by now-Vice President Joe Biden, were not equipped to handle the accusations of sexism and racism that were lobbied at them. “As pampered denizens of a virtually all-male bastion,” Margaret Carlson wrote back then, “many senators were slow to grasp the seriousness of the sexual harassment issue.” In another article, Jack E. White lamented the lack of public credence given especially to African-American women.

“In this postgraduate Skull and Bones, most of whose members hardly need to worry about where their next million is coming from, it is hard to empathize with someone worried enough about her career that she would overlook offensive conduct until it became literally a federal matter,” Carlson added. “Senators don’t interact with women as colleagues—they only have two—and most other women they come into contact with are subservient.”

Carlson predicted the feminist backlash against the Senate after Hill’s hearings: The next year four women were elected as Senators, a record number at the time. The press dubbed it the “Year of the Woman.” Those reverberations for women in politics are particularly relevant now that single women hold more political power than ever, and a female candidate is the current frontrunner in the presidential race.

MORE: How Anita Hill Paved the Way for Women in Government

Thomas’ Silence

In perhaps the most uncanny prediction of all, Michael Kramer observed that Thomas, even before Hill’s testimony, refused to express any strong political opinions at his hearings—a sign of how Thomas would act once he reached the highest court. “When pressed on matters of the moment, he backed away from most every opinion expressed. Incredibly, he told Senators with a straight face that he had ‘no opinion’ on Roe v. Wade, thus marking himself as probably the only person in the U.S. without a view on the Supreme Court’s landmark abortion-rights decision.”

Thomas has since earned a reputation for remaining silent on the court, refusing to ask questions or offer opinions like the other justices. He broke his silence for the first time in 10 years in February.

Read the full 1991 issue about Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas, here in the TIME Vault: Sex, Lies & Politics

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com