When Howard Marks began smuggling hashish in 1970, the drug trade was made up of thousands of smalltime players dealing in pounds and ounces. By the time the Oxford graduate was arrested in 1988, he had become one of an elite group of trafficking kings moving drugs by the ton load. He said his biggest single shipment was 30 tons of cannabis, worth about $100 million, which he shifted from Thailand to Canada. His global enterprise also moved daunting amounts of Colombian Gold marijuana through Florida, Moroccan Black hash through Spain and Red Lebanese into England.

This growth of global millionaire (and later billionaire) drug traffickers may have simply been a logical result of black market capitalism. The counterculture of the 1960s created millions of drug consumers in North America and Europe. As profits were so huge, traffickers had plenty to reinvest and become bigger and bigger players.

But Marks — who died over the weekend — showed particular entrepreneurial skills in carving out a global business, helped by his Oxford connections who included everyone from British secret agents to aristocratic financiers. Marks claimed never to use violence, unlike the Colombian, Mexican and Jamaican crime kings who would follow and unleash bloodbaths in their countries as they took over the trade.

In Britain, Marks has been a folk hero since that 1988 arrest. I remember it especially well as he had lived in the nearby city of Brighton and his daughter Myfanwy was a year above me in my secondary school. The hashish he had a hand in was also popular among the youths smoking joints in the local parks. We teenagers swapped stories about how Marks had used his cover as an informer for the British spy service MI6 to get out of jail, or smuggled hash into America in the sound systems of fictional rock bands.

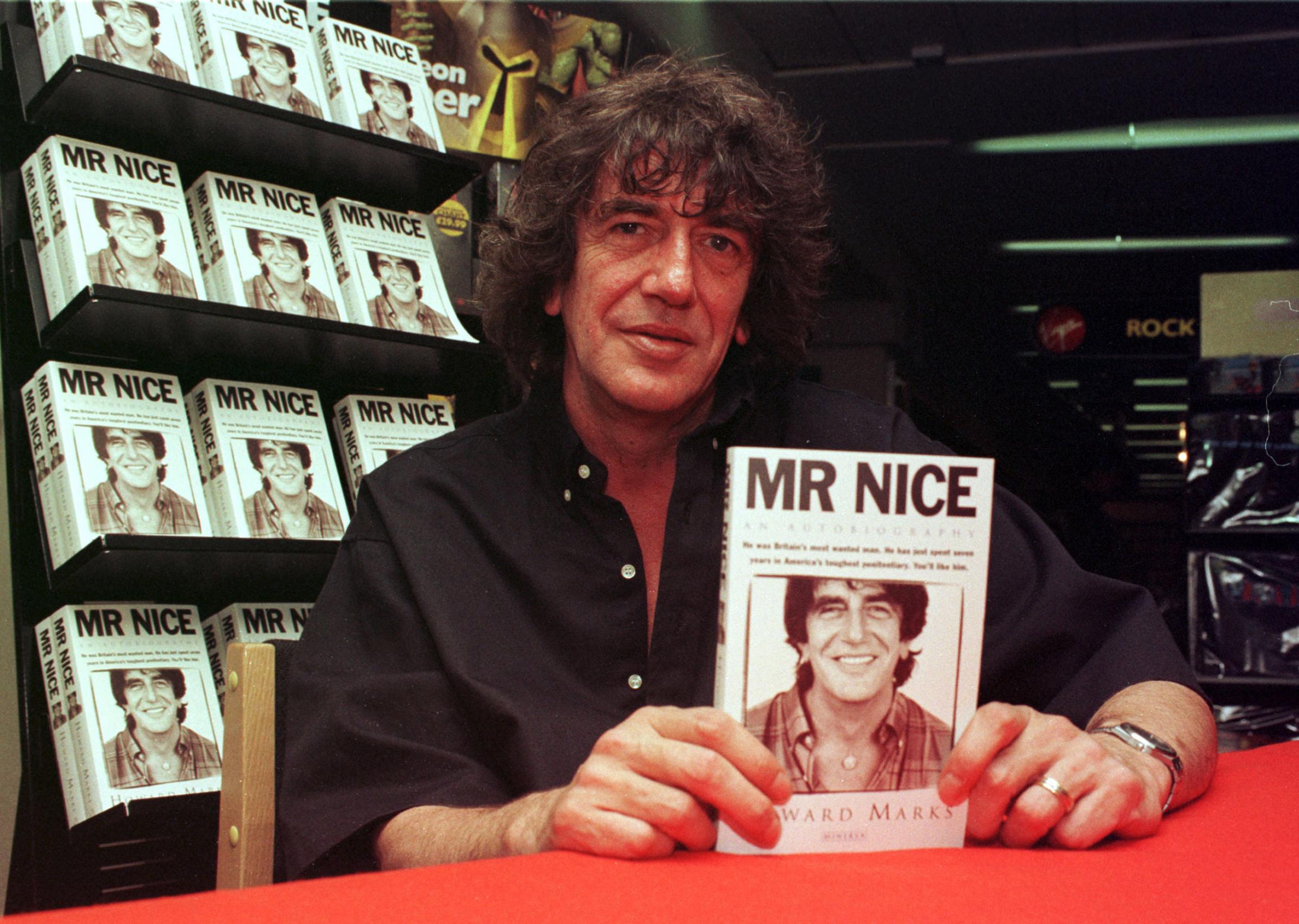

After Marks was released from a federal prison in Indiana in 1995, he consolidated his celebrity status with his bestselling book “Mr Nice” (after one of his 43 aliases). He also made cameo appearances in movies, such as the cult classic Human Traffic where he talks about “spliff politics.”

When I saw him at a decriminalize cannabis march in 1998, he was the star speaker and had the crowd in the palm of his hand. “It’s easy to smuggle tons of marijuana into England,” he said to raucous laughter. “I know from personal experience.” His image as a gentleman smuggler contrasted with the drug traffickers I would find when I arrived in Mexico in 2000, warlords in charge of their own militias, who would drown the country in blood.

Hailing from a working class Welsh village before winning his place at Balliol College, Oxford, Marks said that he had never hoped to get rich off cannabis. “It was part of the peace and love movement so I thought: ‘Obviously they’re gonna legalize this shit soon rather than letting us become millionaires,'” he told the Guardian in 2013. Yet he proved extremely good at becoming exactly such a millionaire trafficker.

He linked up with an Irish Republican Army gunrunner to help him smuggle through Ireland, and with affiliates of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, to get product out of Lebanon – which in turn got him a part-time gig as informant for MI6. He created a range of front companies with their own sophisticated paper trails including a travel agency and a wine importer, techniques taken on by many traffickers that followed. He banked profits in Switzerland and Hong Kong, which were also later favored by Latin American narco kings. “Money laundering and money transfer was much easier in those days than now,” he later told the Daily Telegraph. “You could literally fly into Switzerland or Hong Kong, which is what I did mostly, with a suitcase full of money.”

Among Marks’s vast global web of connections was the 3rd Lord Moynihan, who ran brothels in the Philippines, as well as some heroin. It was Moynihan who betrayed Marks by wearing a wire for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in one of its then most sophisticated operations. Led by the efforts of Agent Craig Lovato, the DEA used U.S. racketeering laws and worked with police in various countries, getting the Spanish to arrest and extradite Marks. Lovato said the case, which would become a blueprint to go after Latin American crime kings, was important to show that no drug trafficker could escape forever. “He had somewhat created an aura about him that he was untouchable,” Lovato said.

As well claiming to be a pacifist, Marks differed from the modern billionaire traffickers as he always said he only smuggled marijuana. While Mexican cartels also traffic pot, they make the lion’s share of their money from cocaine, crystal meth, and heroin. Marks said he didn’t feel his own crimes led to today’s violent drug trade, but blamed law enforcement for the bloodshed.

“It became nastier and nastier, particularly when the penalties were increased because obviously that means you’ve got to get harder and harder nuts doing it,” he said in a 2011 interview. “It’s progressed to a far more violent affair than it was. But I think that’s inevitable if it stays illegal. That’s just another argument to legalize it as far as I’m concerned: stop funding violence and terrorists. That might be a good idea.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com