Thirty years ago, I stumbled into my calling by chance as a 22-year-old headed to medical school. One afternoon, I was walking through New York City’s East Village, and a tiny sliver of a storefront caught my eye. I went inside and started talking to the owners—a husband and wife named Angel and Carmen Perez. They told me they were both recovering heroin addicts who had quit their jobs working for the New York City subways to pursue their dream: creating a Museum of Addiction. They had both been diagnosed with AIDS, and were determined to see this museum rise before they passed away.

They took me to the back of the shop to show me scale models of the museum, which they’d constructed out of tongue depressors and toothpicks. They had blueprints for each floor and intricate drawings of every exhibit. They pulled out a loose-leaf binder thick with rejection letters from Donald Trump and other wealthy New Yorkers whom they’d written to for help. While it was clear that these were form letters, the Perezes didn’t see them that way, and held onto hope that the next request was going to lead to the funds they needed to bring their museum to life.

I was moved by their courage and spirit, and I thought they deserved attention. I went home, pulled out the Yellow Pages (remember them?) and began calling down all of the local TV stations to see if any might do a story. No interest. I flipped to the radio stations, and started calling them as well. No interest whatsoever. At some point I dialed the number of a small community station. The news director told me it sounded like a great story, but that they didn’t have anyone to cover it—so why didn’t I do it myself? That afternoon, I took a tape recorder and went back to interview Angel and Carmen. From the moment I hit “record,” I knew that this was what I was going to do for rest of my life. The story aired on the community that evening. A producer from National Public Radio in Washington, D.C., was driving through New York City, happened to hear it, and picked it up for national broadcast. I withdrew from medical school. My fate was sealed.

Twelve years ago I started StoryCorps to give everyday people the chance to be listened to and leave a record of their lives for future generations. It’s a very simple idea: We have booths across the country where you can bring a grandparent, a spouse, a friend—anyone you want to honor with an interview. There, you’re met by a trained facilitator who brings you inside the sound proof-booth, sits you across from your interview partner, and hits “record.” For 40 minutes you ask questions and you listen—many people think of it as: “If I this was to be our last conversation, what would I ask of or say to this person who means so much to me?” At the end of the interview, you walk away with a copy of the interview, and another goes to the Library of Congress so that someday your great-great-great-grandchildren could meet the person you chose to honor with an interview.

Since 2003, a quarter of a million people have participated in StoryCorps across the nation—making the largest single collection of human voices ever gathered. Because of the nature of the questions asked (“What are the most important lessons you’re learned in life?” “How do you want to be remembered?), in many ways StoryCorps is collecting the wisdom of humanity. We’ve found that much of this wisdom revolves around people’s work lives. Our new book, Callings: The Purpose and Passion of Work, collects 53 of the most compelling and poetic conversations from the StoryCorps archive. There’s a great deal to learn from these voices.

“It doesn’t even seem like much time goes by.”

Sharon Long was a single mom working seven days a week, including a job at a Dairy Queen and cleaning a dentist’s office, to support her two daughters. At the age of 40, as she was registering her oldest daughter for college, she mumbled to herself: “I sure wish I could go to school.” The woman enrolling her daughter overheard her and said: “You can! I’ll help you.” Sharon signed up for a degree in art. When she learned she was required to take a science class, she told her advisor that she was terrible at science. He suggested she take anthropology. “I didn’t even know what it meant. So I went home and I looked it up, and I thought: ‘The study of mankind—that sounds interesting!’” She walked into her first anthropology class and “Bang! I decided what I wanted to be when I grew up.” After Long graduated, she spent decades working as a forensic anthropologist—reconstructing faces from skulls—the job she was born to do. “It doesn’t even seem like much time goes by. You forget to eat, you forget to get up, you forget to drink water. Everything just goes into suspension. And then fifteen hours later, I have a face… It just seems like it’s all been a big long dream.”

“Life’s just too short.”

Barbara Abelhauser spent 14 years working an office job. She was miserable, she tells her boyfriend in a StoryCorps interview. “Then I work up one day and I was like” ‘Life’s just too short!’” She quit to pursue the job she’d always dreamed of: bridgetender. At the time she recorded her StoryCorps interview, Abelhauser sits in a booth smaller than a closet on the Ortega River Bridge in Jacksonville, Fla. “I’ve been sitting in the same exact spot for eight years, and I see the passage of the seasons,” she said. “I see the alligator that hangs out below my window in the summer, and when she lays her eggs and they hatch, I hear the barking of the baby gators. There’s manatees and dolphins that come by. There’s a night heron that sits just below my window all night long every night, except when the algae bloom. And the sunsets and sunrises are like snowflakes—there’s no two that are exactly alike. People don’t realize we exist. They’ll walk past us and say the most intimate, private things and we hear them.” Barbara told her boyfriend “I took a pay cut for this job, and that was hard. But you know, I could get hit by a bus tomorrow, and if that happens I want to have woken up that day and not thought: ‘Ugh, I don’t want to go to work!’”

“You have to do what you love.”

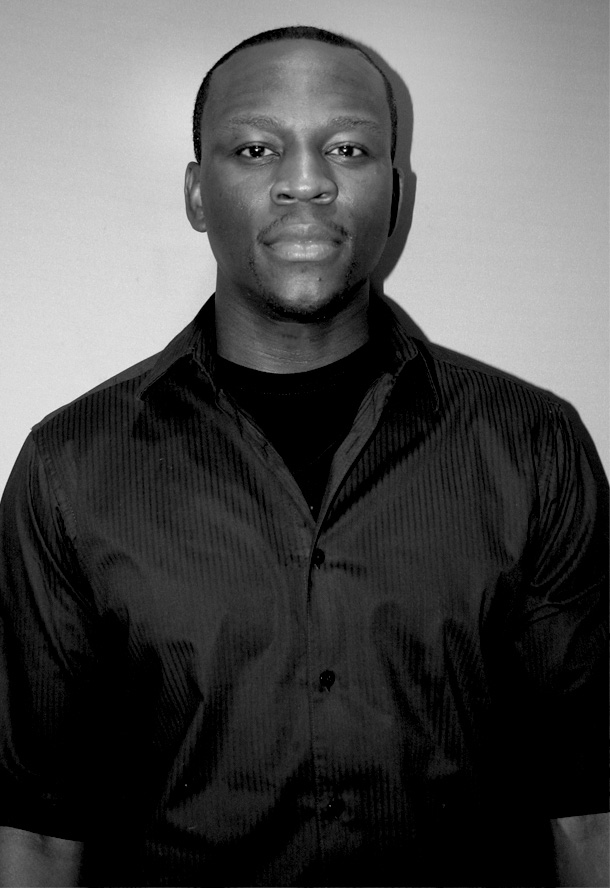

Ayodeji Ogunniyi was on his way to medical school when his father, a Nigerian immigrant, was robbed and murdered in his taxi in Chicago. A few days later, the killers were apprehended—3 young people. At the time Ogunniyi was tutoring at-risk kids at an after-school program for extra money. He realized that his students’ backgrounds resembled those of his father’s killers. At StoryCorps, he remembers a class he was teaching shortly after his father was killed. He asked each of his students to read aloud, and one of the kids, a tough 16-year-old, stormed out of the classroom. Ogunniyi followed him into the hallway and asked what was wrong. “It’s hard for me to read.” The young man told him, weeping. “There are many people that cry because they’re hurt or they’ve been neglected,” Ogunniyi said. “But to cry because you couldn’t read?” Ogunniyi got the young man the help he needed, and he learned to read. “That’s when it dawned on me: ‘You have to do what you love.’ So that’s when I said, ‘I’m going to follow my heart and become a teacher!’”

These are just a few examples of men and women who have stories to tell, wisdom to share and lessons for us all about leading rich, fulfilling and meaningful work lives. They’re a reminder that we’d all be wise to answer the question at the heart of that famous line from poet Mary Oliver: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

Adapted from Callings: The Purpose and Passion of Work, copyright © 2016 by Dave Isay. First hardcover edition published April 19, 2016, by Penguin Press. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com