Tax Day–which is April 18 this year, not April 15–is one occasion in which history offers little consolation. As you tally up your withholding and deductions, it may not help to know that you’re also paying into a system created to fund World War II.

When the modern income tax was introduced in 1913, it was constructed as a tax merely on the very top earners and was essentially irrelevant to most Americans.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

That changed in 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor. The entire nation was mobilizing for war, and money was desperately needed. At the time, the idea of running a deficit was seen as disastrous, says Joseph J. Thorndike, author of Their Fair Share: Taxing the Rich in the Age of FDR and director of the Tax History Project. To pay for the war, Congress passed a new Revenue Act that nearly doubled the number of Americans who would have to pay income taxes. TIME called it “the biggest piece of machinery ever designed to separate dollars from citizens.”

Though the amount raised was important in the short run, it was the expansion in the number of people paying that fundamentally altered U.S. tax structure. The middle class had pitched in before—paying a tax on a purchase was seen as totally normal—but most people had never written a check to Uncle Sam. Now that link would be set in stone.

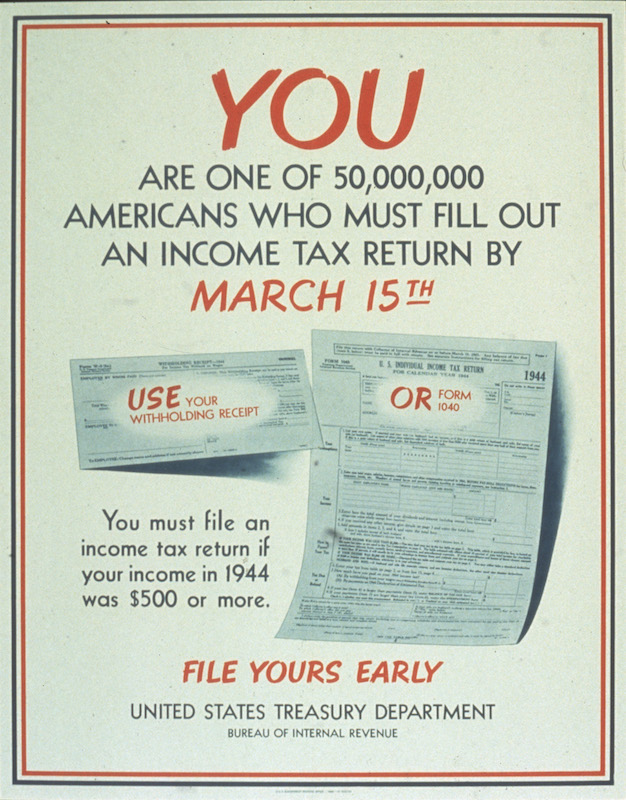

TIME’s coverage of that looming date was headlined The Ides of March, 1943. “This week the U.S. citizen faces a hard and stubborn fact of wartime living…” the article began, “the U.S. Treasury on March 15 will demand and get more money from more people than at any time in the history of the republic.” Going into tax day that year (about a decade before the big day moved to April), the government expected to receive 40 million returns from citizens—far more than the 26 million that had been filed the year before.

Read more: How April 15 Became Tax Day

Citizens unaccustomed to paying up left their taxes for the last minute (which you, reader, surely know nothing about) and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau guessed that those late-payers were waiting for some imaginary last-minute government reprieve. Still, there was reason to believe that the nation, if not exactly eager to pay, was ready to fork over the cash. “If the American citizen does come through,” TIME noted, “it will be more because of inherent patriotism than because of sound tax policy.”

That patriotism—the moral imperative to at least sacrifice dollars while others sacrificed their lives—was enough to carry the Revenue Act through Congress, just as it had carried taxes like the temporary tax imposed during the Civil War. But after World War II, the 1942 tax structure stuck around. Even under Republican administrations like that of Dwight Eisenhower, balancing the books was prioritized over cutting taxes. Both sides of the aisle were resigned to the fact, Thorndike says, that “the war sort of permanently expanded the size of American government and there really was no going back all the way.”

Even major tax reforms that followed, like the Reagan-era cuts in the 1980s, didn’t overhaul the foundation. So, in Thorndike’s view, we are still living under the structure created to serve the needs of World War II.

Not that that’s a bad thing.

He sees public willingness to pay taxes not as a matter of concrete numbers but rather of return on investment. Though nobody likes to pay taxes—Americans are hardly unique there—people of all brackets are generally willing, he says, to pay for value they get back. In nations with extremely high taxes, like those in Scandinavia, citizens pay up not because they like taxes but because they can see what they get in return. In the U.S., people are also generally fine with paying specific taxes for specific goods, like Social Security. He traces any unwillingness to pay to the feeling that the money is going to waste. “It’s misleading to say we’re uniquely anti-tax. Americans have long recognized that taxes are the price we pay for civilization,” he says, quoting Oliver Wendell Holmes. “Nowadays Americans are skeptical of the value they’re getting for their tax dollars, and that erodes their willingness to pay taxes.”

Willing or not, however, the time has come.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com