The deepening standoff between Congress and the president over the replacement of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in February, threatens to damage yet another key part of what Patrick Henry once called the “crazy machine” of government. Some might imagine that the nation’s founders would be appalled if they saw government so paralyzed. In fact, it might seem to them more like deja vu.

Even in its earliest years, Congress faced seemingly intractable problems that might have crippled our new government before it got underway. But unlike the majority of our present Congress, the members of the First Congress were determined to make government work—they were afraid of the consequences if it didn’t.

Today’s Congress might find a way out of the weeds by taking a few lessons from the First Congress, which met first in New York and later in Philadelphia, from 1789 to 1791 in an atmosphere hardly less conflicted than the present-day, and was charged with the daunting task of turning the parchment plan of the Constitution into a working government. Many Americans—including members of Congress—feared that it couldn’t be done.

The nascent United States was still less a reality than an idea. As James Madison, who dominated much of the First Congress debate, put it: “We are in a wilderness without a single footstep to guide us.” The country was a shaky collection of sovereign states. The government had no reliable source of revenue. More than 50 different currencies were in circulation. There was no permanent capital. The British threatened the nation’s security from the north, and bellicose Indians did so from the west. Southerners were suspicious of northerners, westerners of easterners, New Englanders of everyone else. Quakers and others were demanding an end to slavery, while southerners threatened secession if government dared to tamper with their “peculiar institution.”

Astonishingly enough, however, the First Congress produced the most successful record of accomplishment by any single Congress in American history. It established the executive departments, the first revenue streams for the national government, approved the first amendments to the Constitution, adopted a program for paying the country’s debts, embraced the principles of capitalism as the underpinning of government financial policy, founded the first National Bank, established the national capital on the Potomac River, and enacted the first patent and copyright laws. Not least, it also established the Federal Court System and the Supreme Court, with John Jay as its first Chief Justice. They didn’t accomplish all this with a group hug; they did it through shameless deal-making, the kind of flip-flopping that is ritually decried by modern pundits, and the suspension of personal principles in order to get things done.

Present-day Americans might well wonder if today’s congressmen would have been up to the tasks faced by the First Congress. But we miss the point if we think that they were made of a different caliber, or that the problems that they faced were so different in kind. The members of the First Congress were not demigods. “We are beginning to forget that the patriots of former days were men like ourselves,” as Charles Francis Adams put it, in 1871. Along with Madison and other exceptional men such as Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth, their ranks were filled mostly with men of average ability. What they had in common was that the great majority of them were professional politicians, mostly lawyers. Few were amateurs, and almost none were ideological zealots. They were men experienced in government, they understood the need for compromise, even on matters of deeply held principle, and they had the experience to do it. Although they differed deeply on many issues—on slavery, centralized government, regional interests, taxation—they wanted the government to succeed. They also believed in politics as a tool for national survival. After all, the right to be political was what they had fought the Revolutionary War for: It was the engine that made republican government work.

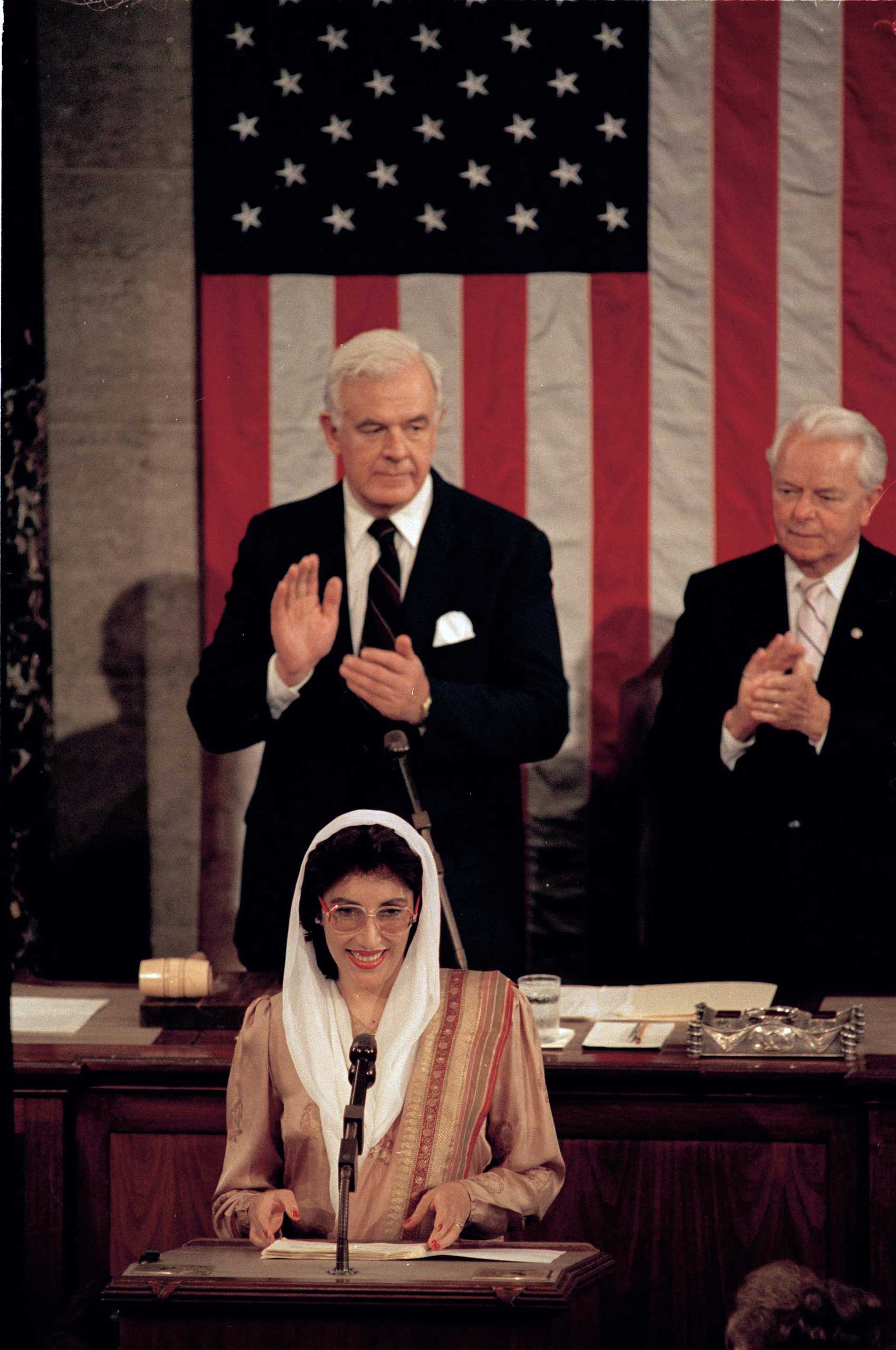

7 Times World Leaders Addressed Congress

So what lessons might members of Congress draw from their predecessors in order to break today’s gridlock? Public faith in our democratic institutions is more important than any single issue. Attacks on the government in order to advance a partisan agenda undermine American values and betray both the spirit and the intent of the founders. In tough times it takes experienced professional politicians to shape the compromises that will always be necessary to keep the country together and move it forward. And that doesn’t just mean compromise on the small stuff: It sometimes means sacrificing deeply-held principles in hope of prevailing another day.

That there is politics involved in Supreme Court appointments is nothing new. But if ever there has been a moment when legislators are called upon to rise above the ideological fashions of the moment in order to preserve public respect for the court, and indeed for government itself, it is now. To attempt to sabotage the president’s clear constitutional power to appoint new members to the court would indeed make the founders cry.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com