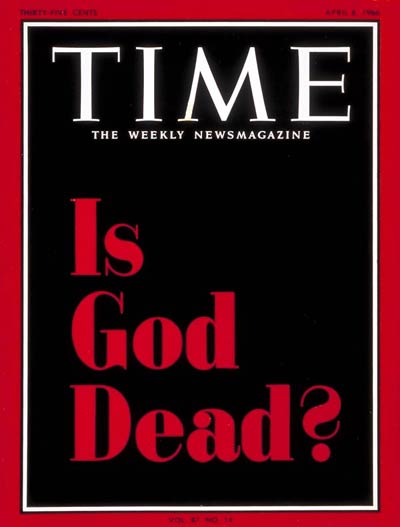

TIME’s 1966 cover story—which provocatively asked “Is God Dead?”—was and remains an ethnocentric proposition with Liberal-Protestant-Christian-Western premises about history and theology. The story of God through the prism of Islam seems to tell a very different story in the modern period.

Despite everything that the Muslim World has been through—from colonialism to violent sectarianism—there is no evidence whatsoever of Muslims en masse abandoning a belief in God or fleeing the mosques. Quite to the contrary, the last few decades have seen a revival of religiosity among previously secularized Muslim societies and among former communist states that tried to wipe Islam out altogether. Many thinkers in the West might assume that the reason for this return to a God-centric approach is due to lack of democracy or freedom to think critically about faith, but I would argue that Islam—as a faith and civilization—is actually an antidote to some of the theological problems posed in TIME’s piece 50 years ago.

To begin with, Muslims’ conception of God refutes what modern people may find to be implausible about the divine. The God of Islam is a decidedly un-anthropomorphic deity. The Qur’an plainly states: “There is nothing like God” (42:11). A common saying among Muslim theologians is: “Your incapacity to perceive of God is your proper conception of God.” Islam’s very testimony of faith begins with a negation, “There is no god,” before the affirmation, “except for God.” Muslim theologians spend as much, if not more, time negating who God is before affirming who God is. In Islamic theology, God is known through named attributes—both intimate and transcendent—not through physical characteristics. God is not, and cannot, be confined to the limitations of time, space or gender.

God in Islam is certainly loving and compassionate, but also vengeful and overpowering. Like the ocean, God is both beautiful and majestic. The experience of God can be as serene as it may be intense. God reveals God’s self in different ways for reasons and wisdoms often beyond our knowledge. As such, Muslims do not always expect God to manifest in the gentlest of ways. Suffering is not so much a theological riddle as it is a reality with a purpose—to know God more profoundly.

In Islam, God entrusts the human being as earth’s caretaker and demands that role be taken seriously. There is no passive religiosity in the hopes of God’s grace. God expects action and struggle—praying regularly, taking care of the poor, practicing self-denial from wrongdoing, enjoining the good and forbidding the evil, and so on. God, then, is experienced through servitude and willing submission.

The popular expectation of experiencing God is often overdramatized. And it is this over dramatization that leads many to feel disappointed when the commercialized experience does not happen. Islam does not promise miracles; rather it allows one to see the miracles that are happening around us.

God is not dead, but rather our ability—because of the distractions of modernity—to be aware of God might be. In one passage, the Qur’an asks: “O human being, what has deluded you away from your most generous Lord?” The commentators quip, it is the generosity of God that distracts us from God!

The excitement of scientific advancement and discovery may be one of those distractions for modern peoples—but it need not be. God and science are not on a collision course. The Qur’an, in fact, urges its readers to search for the signs of God on the horizons and within oneself (41:53) and to contemplate the purpose of life by observing the heavens and the earth (3:190-191). Muslim civilization produced some of the greatest scientists and most important scientific breakthroughs; scientists were not persecuted or maligned for their discoveries of the universe. The notion that science somehow replaces religion is both a misunderstanding of science and religion. Religion’s purpose is to contemplate the “why,” not the “what” and “how.”

To insist that the scientific method is the only methodology to approach all knowledge is no less fanaticism than religious fundamentalism. If the mystic were to tell the scientist to run around his or her laboratory chanting God’s names instead of conducting scientific experiments to determine the validity of a hypothesis, we would dismiss and mock the mystic as a fool. Yet, scientists often insist that the mystic searching for God does so using a methodology that was not made for arriving at metaphysical truths.

One of the names of God that Muslims invoke most often is the Ever Living—Al Hayy. It’s consistent and rhythmic chant can bring elation to the spiritual heart. It is in these chants that the mystic sees God more clearly than they see their own selves. God is closer to you than your jugular vein, says the Qur’an (50:16). Proving one’s own existence, independent of God, is far more confounding to the believer than proving the existence of God. For a Muslim, posing the question, “Is God Dead?” begs the counter question, “If God is dead then how am I alive?”

When whisperings started to spread that the Prophet Muhammad had passed away after a short but intense illness, one of the Prophet’s closest disciples, Umar ibn al-Khattab, went into a temporary frenzy drawing his sword out threatening to strike anyone who would dare say that the Prophet is dead. At that moment, a solemn but calm disciple, Abu Bakr, addressed the mourners with these words: “Anyone who worshipped Muhammad, know that Muhammad has died. Anyone who worships God know that God is alive and will never die.”

It is this sense of God’s permanence and greatness that gives the community of Muslims hope in a dignified existence even during these hard and turbulent times.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sohaib N. Sultan at ssultan@princeton.edu