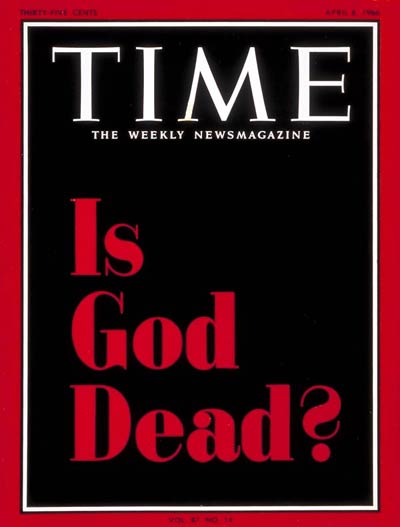

Once, God was dead.

This is a statement not about God, but about me. God did not touch my life, and as philosopher Nietzsche wrote, the sacred no longer influenced the way modern people thought about the world. We killed God, cried Nietzsche’s madman; we exiled the divine from our world. And so I did; for all my teenage years I was convinced that God was a prop for the feeble. Dead to me.

But there were insistent glimpses that grew like the first intimations of sunrise: a word in a conversation or a look in the eye of one I loved or those precious moments of doubting one’s own certainties. Gradually the death of God seemed more like an eclipse; God was blocked, and I could not see. I learned to shift my angle of vision. I came increasingly to believe the words of Rebbe Nachman of Bratzlav, that one who never questions God does not believe in God.

Our society does not live in the wake of God’s death. True, some things are gone forever. Ours is not the God-besotted world of the middle ages. Science has taken areas from the domain of faith and made them vivid and workable where once they were mysteries. Yet all over the world relief workers give themselves to good works because they believe God wishes them to help. People gather in houses of worship, get married with blessings and buried with rites, bring food to the hungry and succor to the bereaved—all in the name of the God who works with human hands.

Each of us are made of infinitely divisible particles. And all of us are parts of an incomprehensible unity. To dissect an animal is not to understand it and to know the botanical name of a flower is not to encompass its beauty. Breaking apart to understand is one way; assembling to worship is another. The totality of life is no less astonishing because we gradually understand more and more, since at its core our existence is not a puzzle but a mystery.

There are ways of looking at the world that allow God back in, and they are not laboratory triumphs but postures of reverence. We can still be humbled by that which we do not know. The domain of the sacred, of awe beyond human grasp, sweeps through our lives both personal and public and reminds us that God lives in the pulse of our world.

Fifty years ago the death-of-God movement, a powerful theological statement, did not envision that religion would surge across the world in often terrible ways. Things are now done in God’s name that are despicable and destructive. In their shunning of human knowledge, norms and decency, some of those who call themselves God’s most ardent advocates seem intent on making us wish that God would indeed die, and so deprive them of the motivation for their depravity.

But that is not the God of faith as I know or respect it. The God of my life is a goad, a guide and a comfort, one characterized by compassion and eternal embrace. Mine is the God of my tradition, whose spark we find in one another and whose radiance is shot through creation. God is the healer of shattered hearts (Psalm 147:3) and will never die.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com