Kweilin Ellingrud, a partner at McKinsey, and Vivian Riefberg, a director who leads McKinsey’s public sector practice, are authors of the new report "The Power of Parity."

Indeed, women make up 46% of the labor force. But on closer inspection, significant inequality still remains, and it has huge economic costs. As we outline in our new report “The Power of Parity: Advancing Women’s Equality in the United States,” furthering women’s equality in the workplace could add $2.1 trillion to GDP in the next decade, or 1% to annual GDP growth in the U.S. That’s 10% higher than the business as usual figure in 2025, and the equivalent of adding an economy the size of Texas. So how are perceptions of the U.S. and gender so off the mark?

1. Gender inequality is not a big issue for developed countries like the U.S.

To the contrary: The U.S. has made major progress on some aspects of gender inequality, but inequality remains high or extremely high on six out of 10 indicators studied by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). First is women in leadership and managerial positions: There are just 66 women for every 100 men in such posts. Second is the fact that women do almost double the unpaid care work that men do. Violence against women is a third—there is one incident of sexual violence for every two women. The U.S. is one of the worst-performing developed nations in the world on the fourth indicator—the representation of women in politics. The fifth and sixth indicators are single mothers and teenage pregnancy—issues that often hold women back from achieving their full economic potential. One in four U.S. families is headed by a single mother living in poverty according to the OECD, and, according to one study, the high teen birth rate is estimated to have cost U.S. taxpayers between $9.4 and $28 billion a year through public assistance payments, lost tax revenue and greater expenditures for public health care, foster care and criminal justice services.

2. The economic opportunity is all about getting more women in the workforce.

Most studies of the economic opportunity on closing the gender gap in work focus on labor force participation. We found that this drives only 40% of the total opportunity, and that two other important factors each drive 30% of the economic potential: the mix of part-time and full-time work undertaken by men and women, and the sectors where the two sexes are employed. On average, a woman in the U.S. does 42% of the full-time jobs and 64% of the part-time jobs. On top of this, women are more likely than men to be working in lower-productivity sectors such as health, social work and education, and less likely to be employed in higher-productivity sectors such as manufacturing and business services. Narrowing gender gaps in all three aspects add up to the $2.1 trillion of additional GDP.

3. Women work less than men.

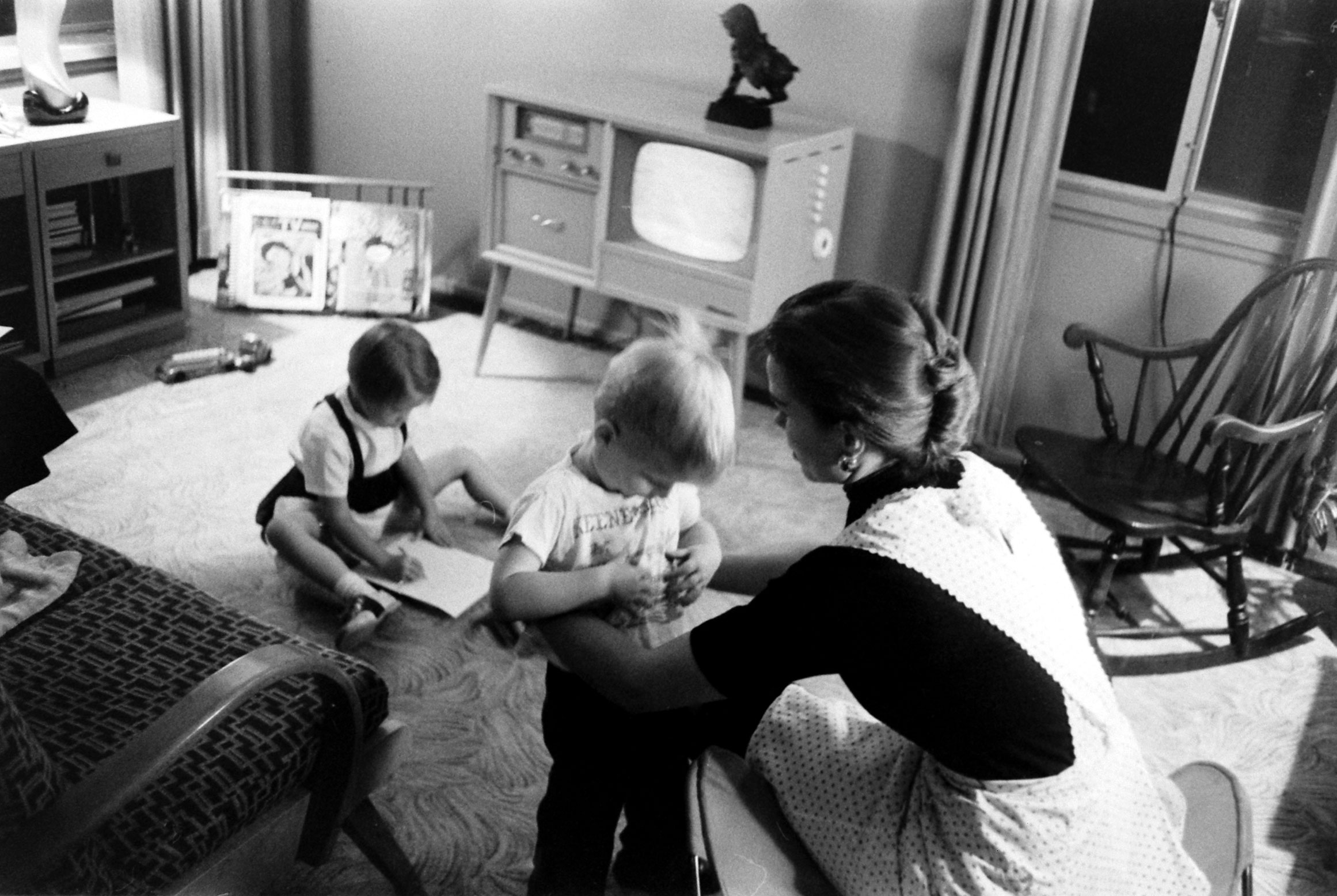

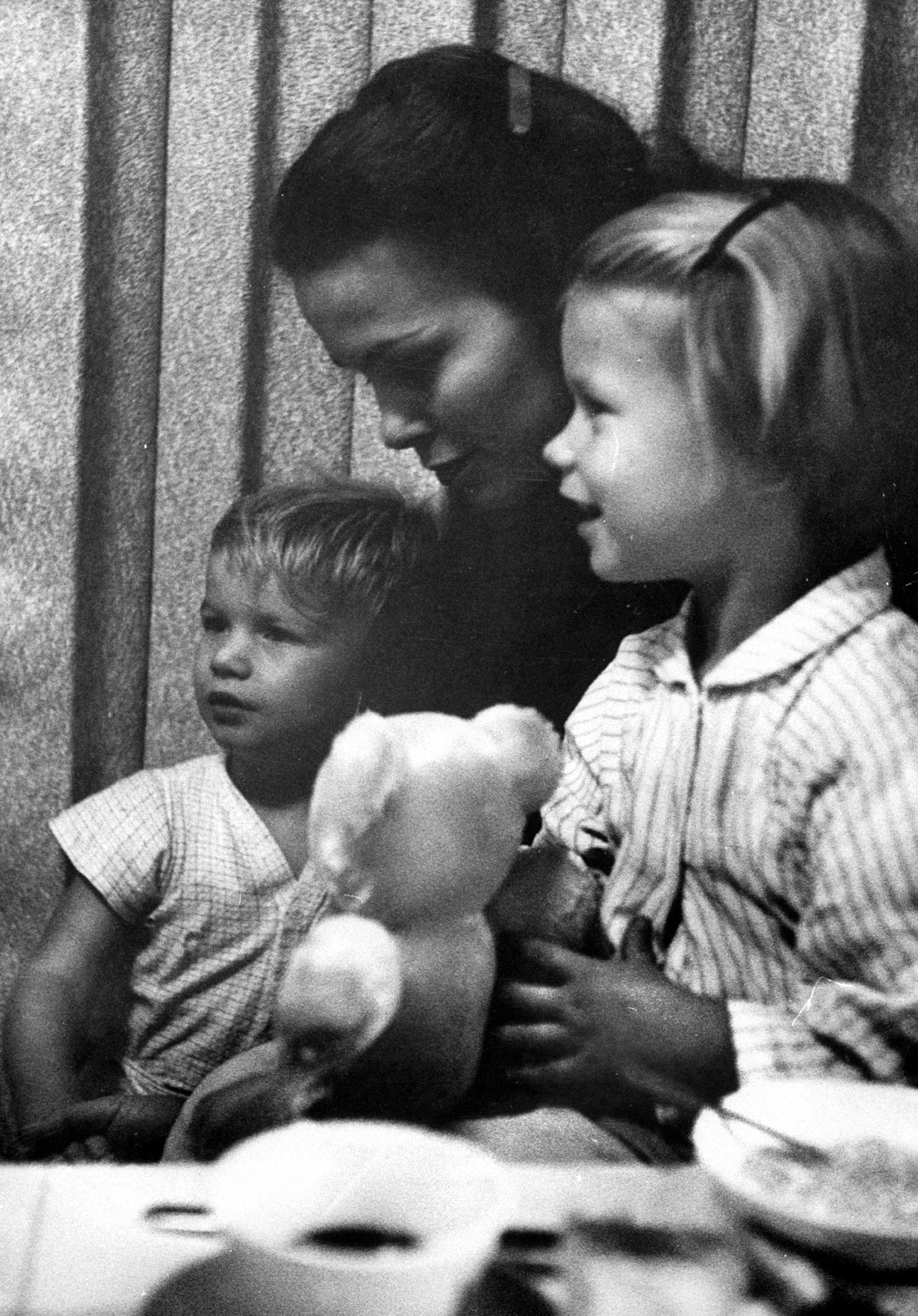

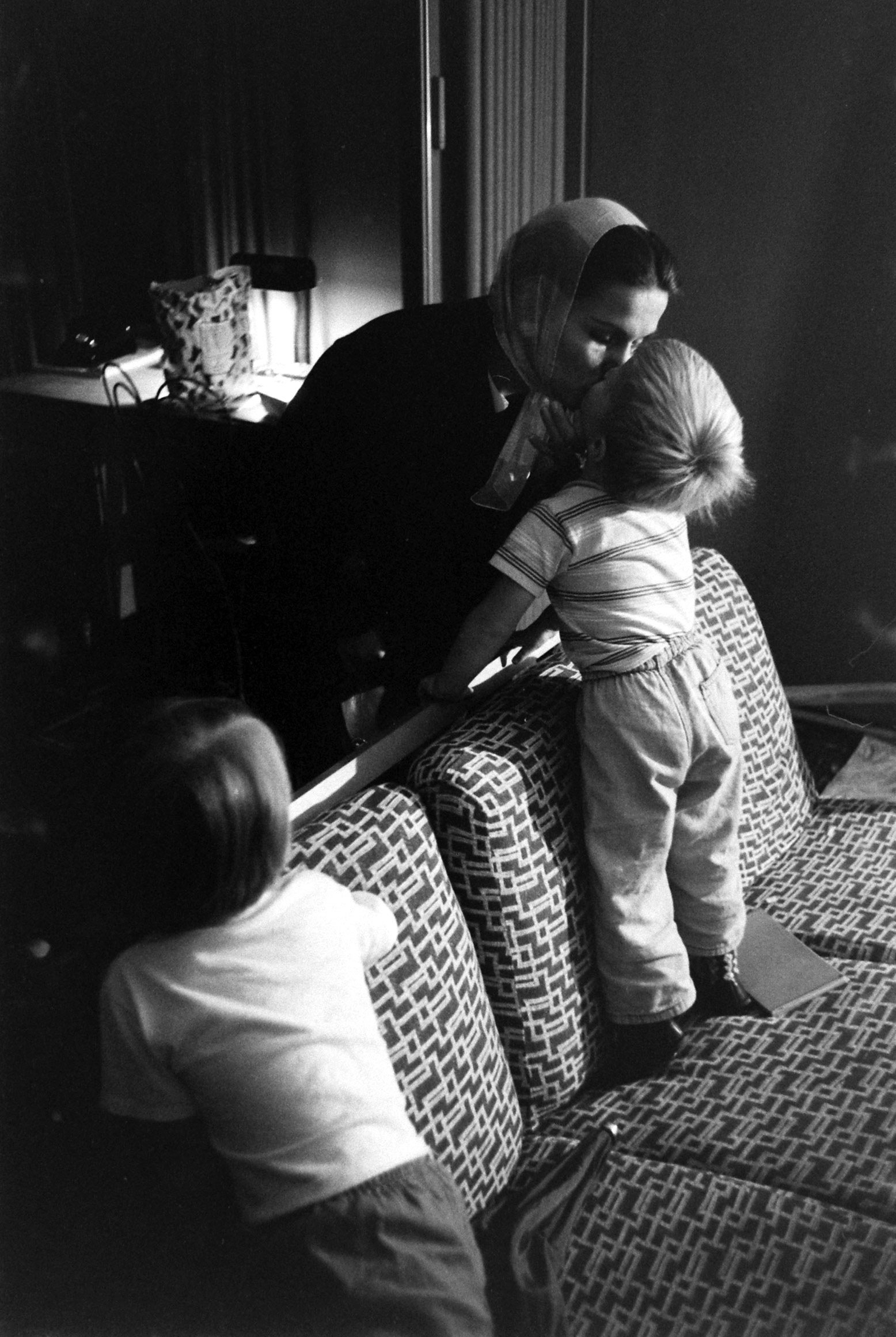

The reality is that women work about the same amount as men. This is because they do about double the amount of unpaid work as men—roughly 70% of it in routine household chores such as laundry or shopping for groceries, and the rest primarily in caring for children and the elderly. This work is not measured in GDP data but, using conservative assumptions based on the minimum wage, this contribution is worth an estimated $1.5 trillion a year in the U.S.

4. More women working will crowd out men.

A perennial worry is that if more women work for wages, men will find fewer employment opportunities or will be forced to spend less time in paid work because they have to devote more time on unpaid household work. But experience tells us otherwise. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the participation of women of prime age in the U.S. labor force increased from 36% in 1950 to 76% in 2000—but the participation of men remained over 90% throughout this period. Achieving the $2.1 trillion incremental GDP opportunity in 2025 would mean that women spend, on average, 35 minutes more per day on paid work based on a 10-hour work day. This increase in hours worked by women could be achieved by men allocating more of their leisure time to helping out around the house. Men, on average, spend about one hour more each day on leisure activities than women do.

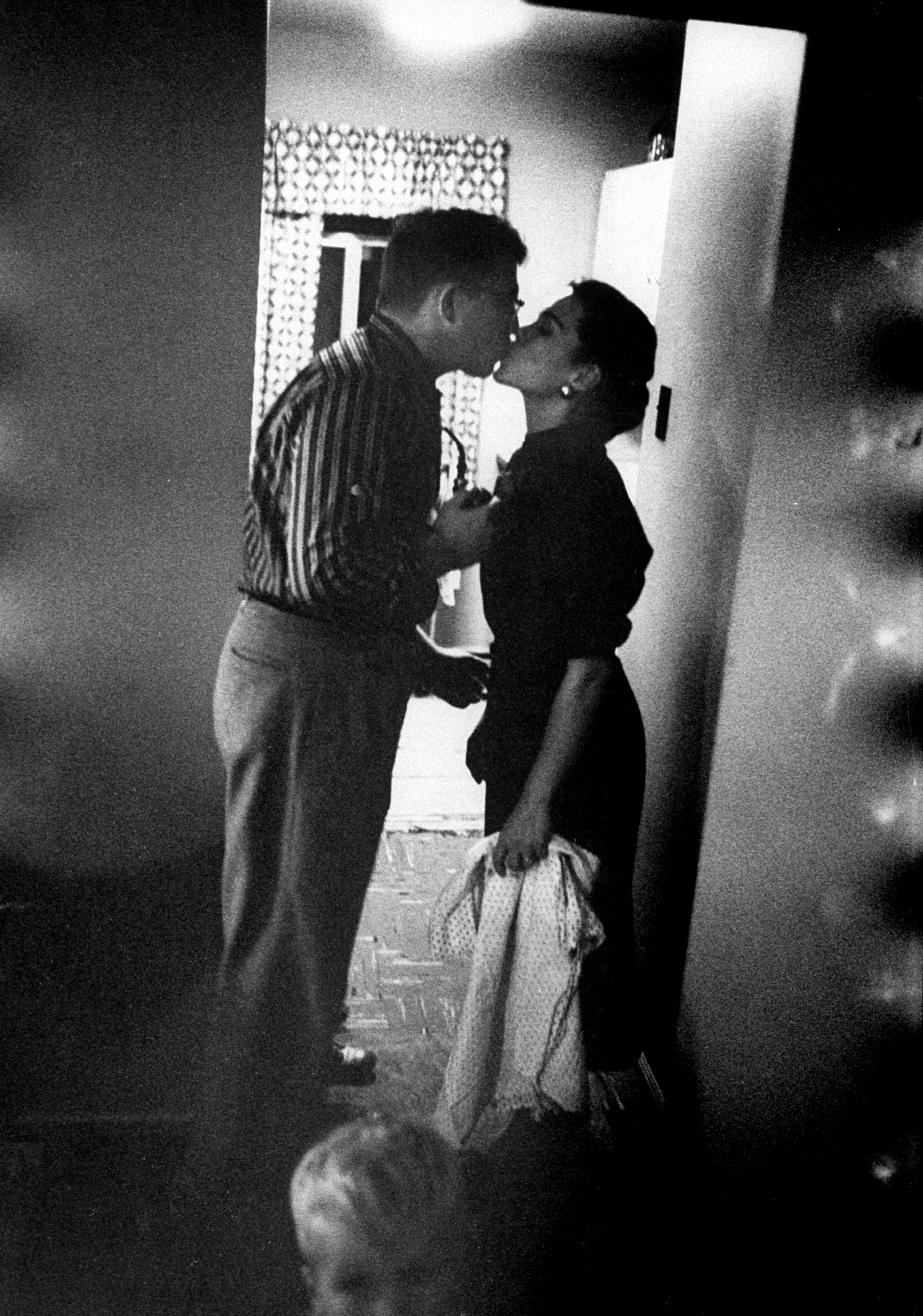

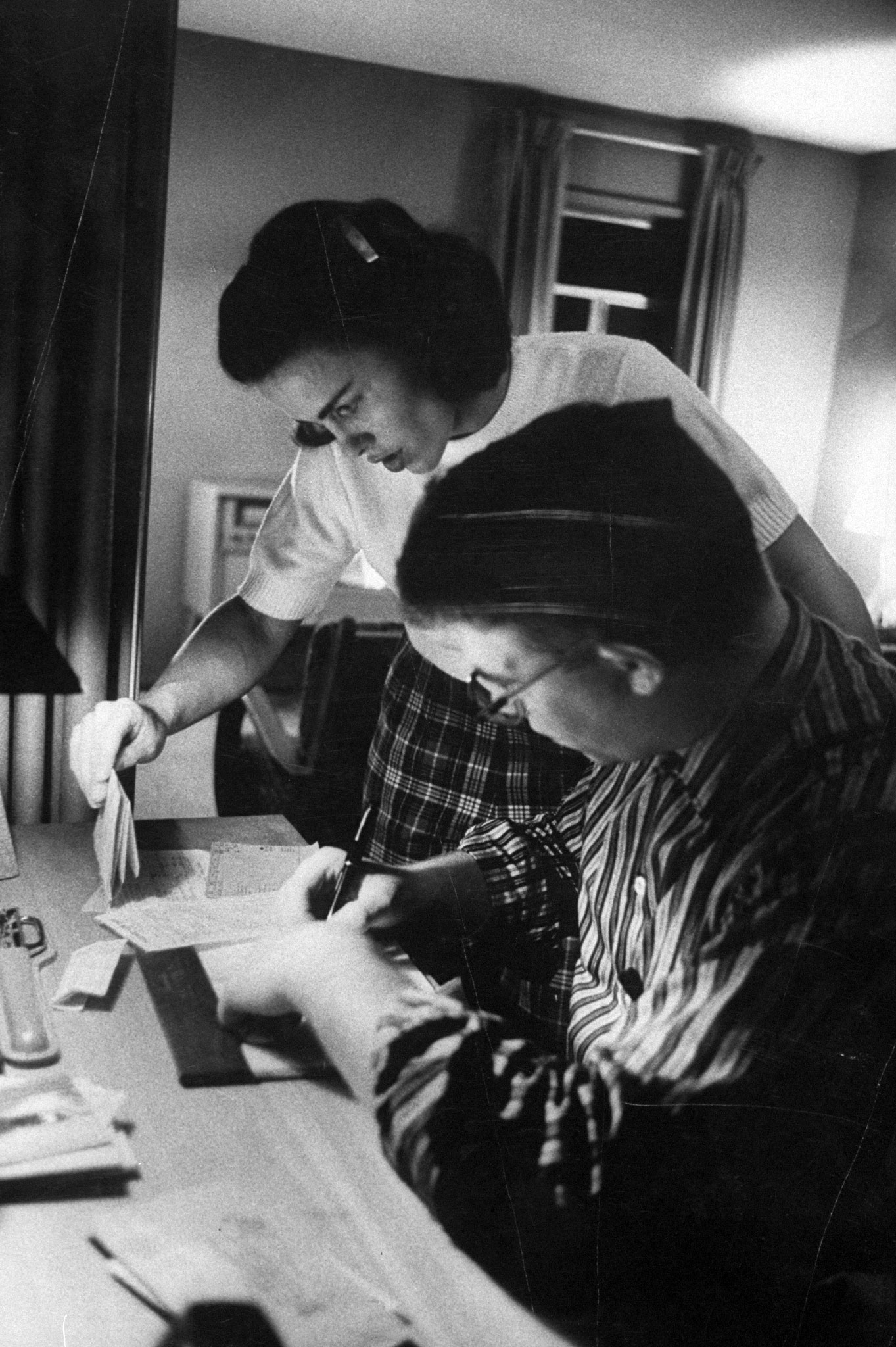

Life Before Equal Pay Day: Portrait of a Working Mother in the 1950s

5. Gender inequality is concentrated in particular parts of the nation.

There is some regional concentration, but the fact is that gender inequality is a national issue—and a national opportunity. There is some regional concentration. Ten of the 12 southern U.S. states appear in the bottom quartile of scores on teenage pregnancy and single mothers, and eight of the 12 on political representation. On four of the six indicators on which inequality is high or extremely high, 10 states account for more than half of the women affected. But the fact is that gender inequality is a national issue—and a national opportunity. Narrowing gender gaps could add 5% to the 2025 GDP of every state, and 25 states could boost their GDP by 10% or more.

So how can gender parity become a reality in the U.S.? Businesses can promote gender diversity in recruitment, performance evaluation and by introducing flexible work arrangements. Governments can consider ways to make paid parental leave and improved child care a reality for more men and women, and can introduce state- and city-level programs to reduce single mothers living in poverty. More cross-sector collaboration between governments, businesses and non-profits is needed. Change is often gradual, but given the size of the gender parity prize, closing the gap in work and society is well worth the effort.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com