This post is in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A version of the article below was originally published on the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

In the course of researching how South Asian writers circulated in literary London between the World Wars, I spent some time immersed in the Harry Ransom Center’s expansive P.E.N. archive. Although I was primarily focused on London P.E.N.’s gatekeeping function—P.E.N. members such as the editor John Lehmann of the Hogarth Press were influential in determining whether and how the work of young South Asian writers reached a British readership—I also appreciated the dynamic insights the P.E.N. archive provides into the early identity of the organization, which has operated continuously since its founding in 1921.

Today, P.E.N. (Poets, Essayists and Novelists) International has an explicitly political identity. The organization runs international campaigns to support freedom of expression by advocating for writers who have been criminally prosecuted and imprisoned due to their work. When P.E.N. was established in London during the early 1920s, its founding members espoused the values of freedom of expression and international peace that continue to anchor contemporary P.E.N.; rather than forming political campaigns, however, early P.E.N. members fore-fronted hospitality and society among writers internationally as means to facilitate peace among nations.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

A quick glance at the P.E.N. homepage today provides an immediate sense of the organization’s mission and objectives: subheadings include “Writers At Risk,” “Impunity in Honduras,” “Linguistic Rights and Education,” and “International Advocacy.” But during the early years of the organization, political activism in the name of P.E.N. was actively discouraged by early leaders. A P.E.N. newsletter dated November 15, 1927, covers a speech by P.E.N. President John Galsworthy, in which he cites a resolution recently passed by P.E.N. leadership:

Literature, national though it be in origin, knows no frontiers, and should remain common currency between nations in spite of political and international upheavals. In all circumstances… works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion.

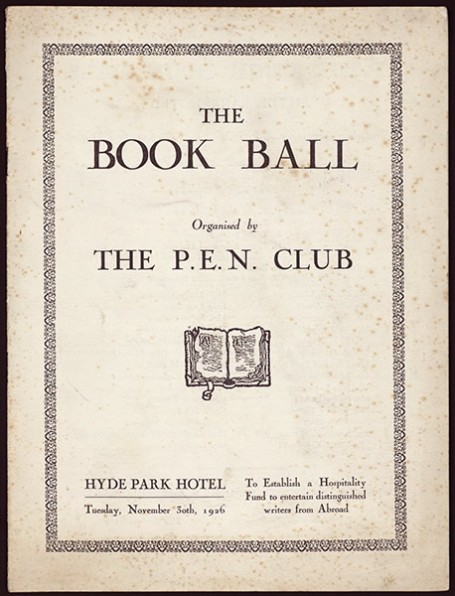

P.E.N. emerged during a moment of postwar optimism regarding the potential of human fellowship to overcome the contingencies of geopolitical power. Although this optimism would recede with the advent of fascism and the onset of World War II, it determined P.E.N.’s emphasis on social rather than political relations during the interwar period. In a foreword to the 1926 P.E.N. Club Book Ball fundraising gala program (pictured below), Book Ball planning committee member John Drinkwater reflected on the rationale behind P.E.N.’s founding:

It was felt by the founders of the Club that writers the world over formed a class of people whose mental habits and daily occupation made them independent of political prejudices, and inspired them with a living ideal of international goodwill that might in time replace commercial and diplomatic jealousies… It was thought that if writers could be given the opportunity of developing this idea in friendly intercourse, they would, with their faculty of expression, be able to hand it on to the peoples of their respective countries, not, indeed, by direct propaganda, but by personal influence and the general character of their writings.

Here, Drinkwater details the logic behind the formation of P.E.N. as a social rather than a political organization. In the process, he demonstrates the powerful faith his community of liberal poets, essayists, and novelists had in the capacity of friendly individual relationships and civil discourse to effect “international goodwill” and create conditions for peace.

Given this emphasis on the social, it follows that the earliest materials in the P.E.N. archive strongly feature food, drink, and dance. At its founding, P.E.N. identified as an informal “dinner-club” where, according to an early statement on membership criteria, “well-known writers of both sexes can meet,” and where “visitors from abroad can hope to find them.”

Read the rest of this article at the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

Charlotte Nunes is a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Digital Scholarship at Southwestern University. She visited the Harry Ransom Center in June 2015 to conduct research on the circulation and reception of South Asian writers, including Mulk Raj Anand, Ahmed Ali, Raja Rao, and Sajjad Zaheer, in literary Bloomsbury between 1920 and 1940. Her findings will be published in an essay co-authored with Snehal Shingavi, to appear in the collection British Literature in Transition, 1920-1940, edited by Charles Ferrall and Dougal McNeill and under contract with Cambridge University Press. Nunes’s research was supported by a fellowship from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Research Fellowship Endowment.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com