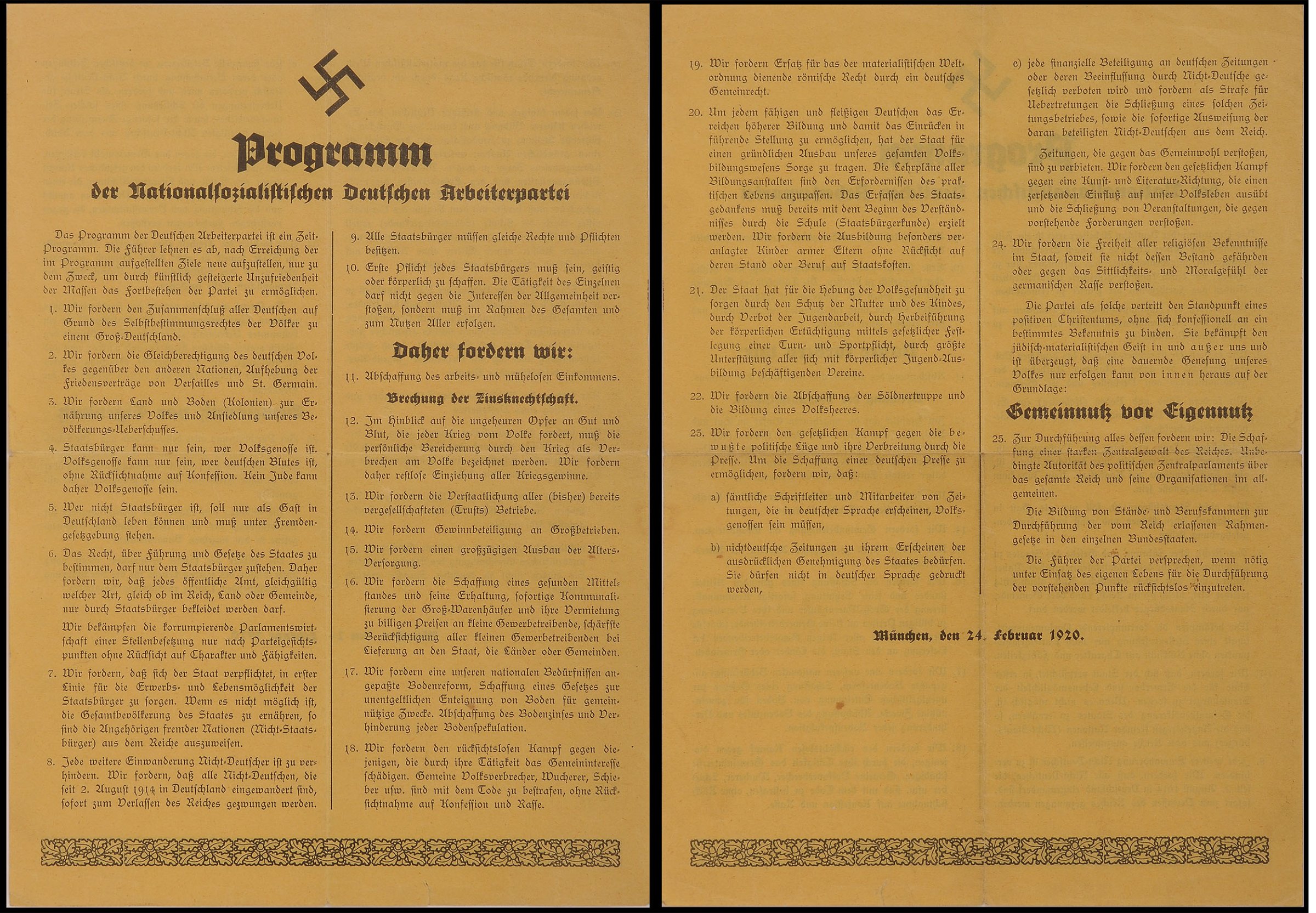

Hitler had joined one of the many small right wing political groups in Munich, the German Workers’ Party, in September 1919. Germany was a country in considerable turmoil and there were many such groups forming, disbanding, forging or breaking alliances, and fighting each other on the streets. The city of Munich was a center of political activity where meetings at its beer halls drew large crowds of people some of whom were attracted by the prospect of violence. By February 1920, Hitler had drawn up this party program together with the original founder of the party, Anton Drexler. It was introduced at a meeting at the Hofbräuhaus on 24 February to which nearly 2,000 people turned up. Hitler was not the main speaker, but when he spoke, some of the crowd became vociferous and violence broke out. However, he managed to overcome the noise and confusion to speak in its favor, and the program was adopted.

This document clearly identifies three fundamental principles that were to underpin Nazi ideology and policy for the next twenty-five years;

‘We demand equality of rights for the German people in respect to the other nations; abrogation of the peace treaties of Versailles and St Germain [between the Allies and Austria].

We demand land and territory (colonies) for the sustenance of our people, and colonization for our surplus population.

Only a member of the race can be a citizen. A member of the race can only be one who is of German blood, without consideration of creed. Consequently no Jew can be a member of the race.’

Thirty-two nations had been involved in the peace talks in Paris in 1919, but representatives of the German government were not invited to attend until it was time for them to receive the peace terms that the Allied nations had agreed on. They were given three weeks to comply, with the understanding that if they did not, war would re-commence. 1919 had been a year filled with revolutionary violence and instability in Germany and in other countries too. The Spartacist Uprising in Berlin, and the Bavarian Soviet Republic had both been suppressed by the summer, but fears of further unrest were still high. The Social Democratic government accepted the terms under protest. Germany was stripped of all its overseas colonies, nearly half of its iron industry, a quarter of its coal industry, 12% of its population and 10% of its European territory. It was forced to accept the clause stating that Germany was guilty of starting the war, to undertake to pay reparations and to severely limit the size of its armed forces.

These terms are not as severe as those Germany had imposed on Russia in 1917 by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. But Hitler was not alone in his view that Versailles had been an utter betrayal of the German people by politicians – a ‘stab in the back’– and that the terms were far too punitive. Along with many other right wing and antisemitic Germans, he laid the blame on Jews. Such a betrayal was inexplicable, in Hitler’s mind, without there being a substantial and deliberate conspiracy to destroy Germany. What is particularly interesting is the emphasis that this program of 1920 places on the other two principles – demands for land, which would later be referred to as ‘Lebensraum’, and for German citizenship to be based on a definition of race which excluded Jews, and that Jews would, therefore, have to leave Germany.

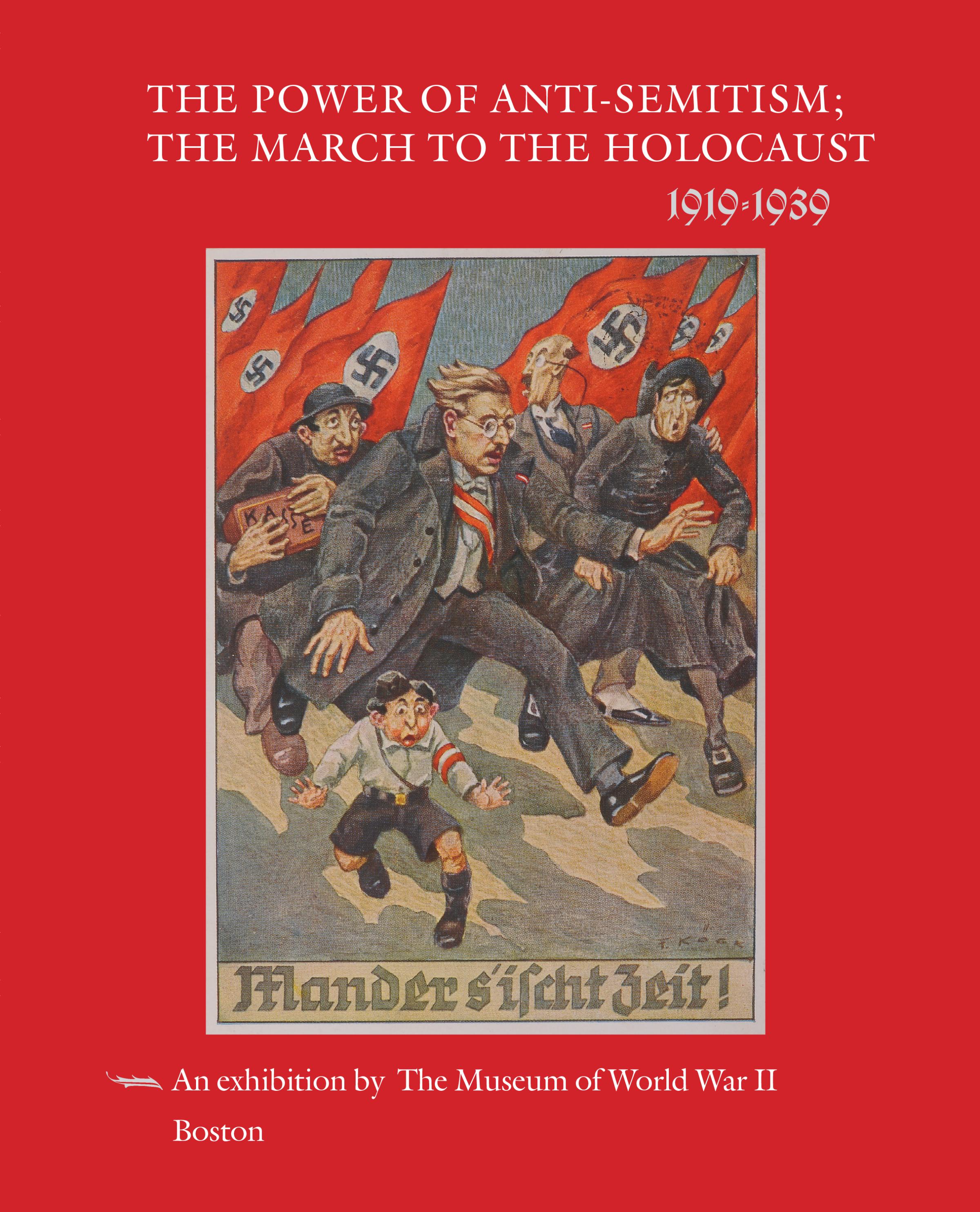

Excerpted from the Museum of World War II Boston’s The Power of Anti-Semitism: The March to the Holocaust 1919–1939 by Kenneth W. Rendell and Samantha Heywood, published in conjunction with the exhibition Anti-Semitism 1919–1939 at the New-York Historical Society.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com