In 1854, America’s political party system — which pitted Democrats against their Whig rivals — was in a state of crisis. Early in that year, Democrats had passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which removed an important legal barrier to the westward expansion of slavery. Months later, in the 1854 midterm elections, incensed Northern voters registered their discontent with that decision by unseating Democrats who had voted for the proslavery law; in the South, they did so by ousting Whigs who had opposed the legislation.

The Democrats would lose close to half of their seats in the House — but, remarkably, they would survive this crisis while the Whigs, who lost a mere quarter of their Congressional delegation, would quickly fade to oblivion. Deprived of their support in the South, the Whigs were no longer capable of carrying the White House — and thus incapable of dispensing federal patronage jobs, the common currency of 19th-century American politics.

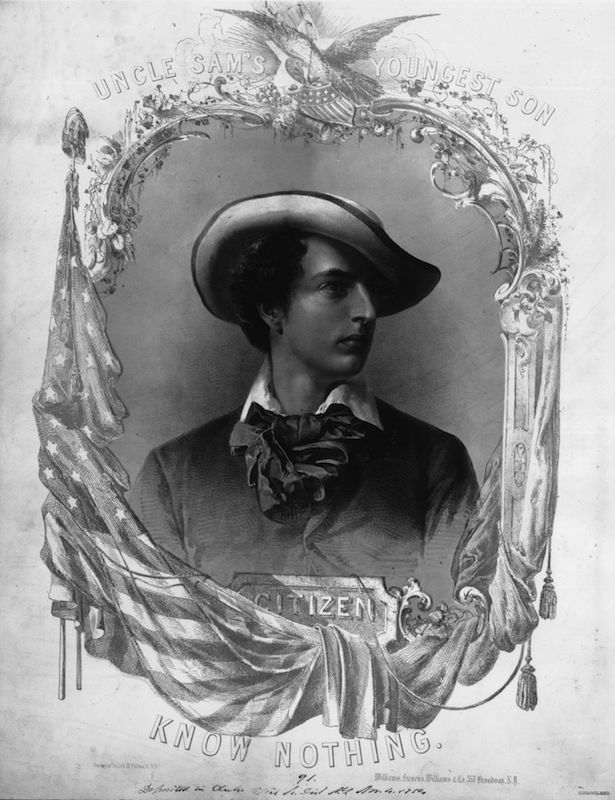

In the vacuum created by the fall of the Whigs, new coalitions would arise. Initially, the most powerful of these was the American — or Know Nothing — Party: a secretive group of white Protestant xenophobes bent on curtailing immigration, limiting immigrants’ political power and foiling the Pope’s illusory influence in the American republic.

Within years, however, the Know Nothings would be gone. How did this happen? Leaders of the new Republican Party — another would-be successor to the Whigs — convinced Know Nothing voters that slaveholders posed a greater threat to the republic than immigrants. They also made the case that, in a changing America, immigrant support would be necessary for parties to gain and maintain political power. Joining the Republican ranks in droves over the late 1850s, former Know Nothings became an important part of the coalition that put Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

Today, as American political leaders struggle to beat back another tide of political xenophobia, they would do well to remember the Know Nothings’ defeat — and how the founders of one of the country’s leading political parties orchestrated it.

Early Republicans accomplished this goal by understanding that Know Nothing voters were cross-pressured by conflicting ideological currents. The most obvious of these currents was xenophobia. Alarmed by the arrival of millions of Irish and German immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s — many of them poor and Catholic — Know Nothings advocated strict limits on immigration and an extension of the naturalization period from five to 20-plus years. If the party failed to do this, Know Nothings argued, Anglo-Saxon Protestants would lose control of the country; elections would be dominated by superstitious voters beholden to the Pope; and democracy would be destroyed.

According to historian Tyler Anbinder, however, xenophobia was not the party’s only concern. An overwhelmingly northern coalition with a strong reformist bent, Know Nothings also advocated goals long associated with the temperance and antislavery movements. As such, they favored bans on the sale and consumption of alcohol and claimed that wealthy southern slaveholders had hijacked the political process for their own personal gain.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Recognizing these cross-currents in Know Nothing politics, early leaders of the nascent Republican Party sought to reshuffle nativist voters’ priorities by putting opposition to slavery ahead of xenophobia. At first, they were unsuccessful. While antislavery was becoming a powerful ideological force in northern life, the movement did not yet possess the organizational footprint that benefitted the supporters of xenophobia, who had been working since the 1830s to build state and local political coalitions.

By the late 1850s, however, that was changing. In the years following the Kansas-Nebraska fiasco and the collapse of the Whigs, both Republicans and Know Nothings had moved to put political organizations in place. The Know Nothings fell back on nativist clubs and fraternal organizations—notably, the ridiculously named Order of the Star Spangled Banner—while the Republicans quickly constructed a party structure from scratch, as grassroots antislavery organizations were not nearly as well developed. It was thus no surprise that the Know Nothings got off the ground more quickly, winning impressive election victories in Congressional and state contests, but by 1856 the Republican Party organization had eclipsed that of its rival. During the remainder of the decade, the Know Nothings would be almost wholly absorbed into the emerging Republican Party, who, according to historian Eric Foner, made few meaningful concessions to nativists’ demands.

How did these early Republicans defeat their nativist foes? They did so by considering Know Nothings’ grievances in full, and by offering a more compelling explanation for the country’s troubles than the one nativist leaders had provided. Yes, Republicans conceded, there were many immigrants in the United States. But, at roughly 14% of the U.S. population, they did not control the country. Nor, as a poor, socially-disenfranchised minority, did they pose a threat to its existence.

Slaveholders, on the other hand, did control the country. Though small in number, they had dominated the presidency, Congress and the Supreme Court for much of the republic’s 80-year history. They controlled the majority of the country’s wealth. And they held one-fifth of its inhabitants in chains. By any objective standard, these slaveholders were the masters of America. And they were using this power, Republicans argued, to enrich themselves, subvert democracy and limit the opportunities of American northerners. In due time, Republicans warned, they would contrive to reintroduce slavery in the North and force unsuspecting American lads to fight an unending series of imperial wars to win more land for slavery. To combat this, Republicans claimed, northerners must recognize the so-called Slave Power’s evil intent and unite in opposition to slavery’s territorial expansion.

It was not just philosophizing, however, that won Know Nothings to the Republican cause. The late 1850s also witnessed prodigious feats of backroom political dealings as well as a healthy dose of pragmatism. During these years, Republicans successfully made the case to nativist voters that, while immigrants did not control the country, they did represent a growing portion of the northern electorate. And that any successful political party would have to win a fraction of their votes.

The Republican Party thus offered Know Nothing voters a better product than what their leaders were peddling: a realistic diagnosis of the country’s problems and a viable path to redressing those problems. This, combined with the Know Nothings’ vacillation on both slavery and immigration, led many former nativist voters out of the Know Nothing coalition and into the Republican Party.

Today, Republicans face an insurrection in their ranks similar to the one confronted by political leaders in 1854. Like their Know Nothing forebears, today’s insurgents are profoundly cross-pressured: they chafe at the prospect of losing their demographic dominance, they rage at an economy that has left them behind, and they inveigh against a party that, for decades, has promised them opportunity but repeatedly failed to deliver. For all this, they blame banks, they blame trade deals, they blame businessmen and politicians. But, in the current election cycle, their foremost target has been immigrants.

Sooner or later, though, someone will offer these disgruntled Republicans a solution that actually makes sense, one that does not blame America’s woes on some of its most vulnerable inhabitants. Should these cross-pressured voters choose to listen and reshuffle their priorities accordingly, America might face a political revolution every bit as profound as the one that rocked the nation in 1861.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sean Trainor has a Ph.D. in History & Women’s Studies from Penn State University. He teaches history and humanities at Santa Fe College and blogs at seantrainor.org.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com