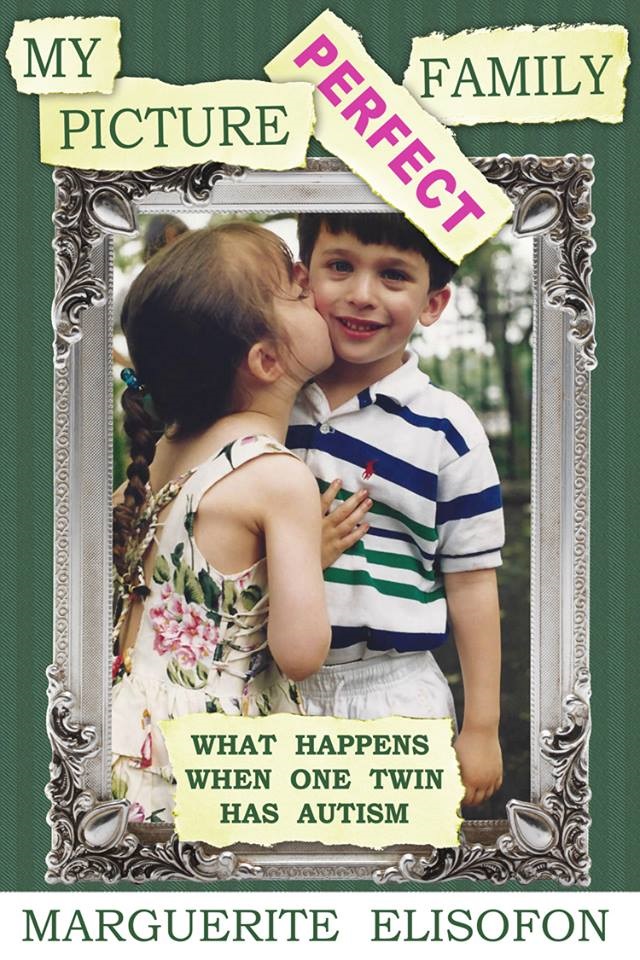

When my twins were born 25 years ago, there were no autism support groups or Internet chat rooms. But, thanks to her neurotypical twin brother, our family recognized early on that something wasn’t right with Samantha. Matt began pointing at objects and asking questions; Samantha rocked and stared into space. By the time she was 12 months old, she’d been diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Delays, although no one actually said the A-word.

While researching treatments, I also worked with Samantha to keep her calm and stimulate her thinking. Along the way, I learned as much from her as she learned from me. Her sensory defensiveness taught me to buy soft clothing and cut out labels (before she tore them off). Samantha wanted to be independent before her body was developmentally ready. Watching her brother dress himself at 4 caused Samantha to throw tantrums. Her sequential motor planning was so poor she pulled her socks on backwards, put her shoes on the wrong feet, broke zippers and tore off buttons. My solution? Sneakers with Velcro, leggings with elastic and loose fitting dresses without closures.

Helping Samantha dress or teaching her anything before she was ready only caused violent meltdowns. I had to learn patience and how to tolerate anxiety while watching my daughter scream in fury because she couldn’t maneuver her arm into a sleeve. “Please tell me when you’d like some help so you can learn for next time,” I’d say, working hard to remain calm. Sometimes the suggestion: “Would you like to do it together?” allowed us to reach the teachable moment.

Most family excursions turned into teachable moments that parents of neurotypical kids couldn’t imagine. At age 8 on the beach our daughter ran over to another family’s umbrella and started slurping down someone’s abandoned Coke. When her brother tried to stop her, she yelled at megaphone volume: “It’s none of your business. Only Mommy and Daddy can tell me what to do.” Many lessons needed to be taught that day.

Sometimes I taught Samantha how to stay calm and appropriate, but the lesson backfired later. Samantha learned to knit and crochet instead of tying things in knots or touching herself when anxious. After 9/11, at the airport when Samantha was 10, security personnel removed the knitting needles from her carry-on bag. Quick diplomacy and explanation—to Samantha and security—were necessary to board the plane and take a much needed vacation. Fortunately, by then Samantha had a few years of Applied Behavioral Analysis and understood choices and consequences.

Although Samantha got A’s on her math tests at school, she had no idea how to apply math to life. When I went shopping with her at the Gap, I discovered my ninth-grader didn’t understand percentages or discounts. Nor did she see how math was essential in the world. Reporting to her teacher, I learned that Samantha wasn’t the only student mindlessly manipulating numbers. After that, her math class began going out for breakfast once a week; each student got a separate bill and practiced adding, making change and calculating tips.

Another real-life math lesson for Samantha was how to handle train delays when we were late for our monthly doctor’s appointment in Washington, D.C. I always offered my daughter hypothetical plans. “If the train is 20 minutes late, and the doctor is running 10 minutes behind, how much time do we need to make up?” The solution might be to buy lunch and soda together instead of separately as she preferred, or go straight to the doctor where she started therapy while I bought lunch. I always practiced “Plan A, B and C.” It was imperative for her to learn how to come up with simple solutions to life’s problems and think on her own.

At their weekly Sunday father/daughter brunches, my husband invented a game: “What Doesn’t Belong?” a) a fork, b) a knife, c) a plate d) a spoon. Giving the right answer wasn’t enough. Samantha had to explain the plate didn’t belong because everything else was silverware. The game quickly progressed beyond simple concrete questions to complicated concepts and geography. Eventually Samantha began posing questions. The game was a lot of fun, and sometimes we discovered there was more than one right answer that could be defended with intelligent reasons.

Although many experts were not optimistic about our daughter, Samantha managed to exceed their expectations. She graduated cum laude from Pace University and enjoyed a serious relationship with her boyfriend, who has Asperger’s, for more than two years. Our daughter was also chosen (over 100 neurotypical actresses) to co-star in an award-winning short film, Keep the Change, about young adults seeking romance and trying to navigate the neurotypical world. The full-length feature is scheduled for release in 2017. Right now Samantha sings with DreamStreet Theater Group and works part-time at a music school with young children. Casting agents, what’s next?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com